The Mistress of Spices: An Analysis of Spices in Indian Mythological History

- EIH User

- October 14, 2023

Indian history and culture are deeply intertwined with Indian Spices. From morning cups of spicy tea to vibrant protection enchantments, from delicious curries to bitter herbal medicine, spices can be found all around. India has always been the “Spice Bowl of the World,” drawing traders from Mesopotamia, Egypt, Arabia, and Greece as well as invaders from the Assyrians and Babylonians, as well as traders from the Romans, Chinese, British, and Portuguese.

Naturally, with the significance of spices to Indian culture, numerous historical and epic books, from the Vedas to the Mahabharata, have referred to them. The earliest written record in India on Spices is found in the Vedas – the Rig Veda, Yajurveda, Samaveda and the Atharveda. Chilies are said to be the child of the Fire God, Turmeric is said to have emerged from the sea when the Asuras and Devas churned it for Ambrosia, and Shabari, a Rama devotee, sowed Fenugreek.

The Indo-American Writer Chitra Divakaruni’s ‘The Mistress of Spices’ metaphorically represents the Indian Spices to explore the different myths and historical tales associated with them. Divakaruni declares in the beginning that this is a novel about magic, mystery, and love, an ode to the relationship of Indians with spices. The stories draw inspiration from old Bengali tales and epics told by her grandmother when she was young. Employing the techniques of personification, magical realism, alienation, and identity crisis, Divakaruni attempts to explore how strong women like Tilo, Lalita, and Geeta break barriers set upon them by a patriarchal society and gain actualization.

Sesame is associated with creation

The protagonist Tilo or Tilottama has magical powers and she uses spices to help people. She holds that spices carry magic and can aid those who are sick, lonely, in danger, or seeking love. She runs a spice shop in Oakland, California. The name Tilo is derived from til or sesame. The Garuda Purana mentions that sesame comes from the pores of Vishnu and was one of the first plants to be cultivated. According to Brahma Purana, sesame is blessed by Lord Yama or the God of Death, which is why they are known as the ‘seeds of immortality’. Sesame is associated with creation and protection, a role given to Tilo in the book. Through the magical powers of Indian Spices, she attempts to help people and save people. To be a mistress, Tilo had to give up her desires and take the body of an old woman. Tilo begins her story by stating that “I am the mistress of spices. I know everything that there is to know about spices and their magical powers. I know where each spice comes from, and what its color means, and what its smell means”. Through this knowledge, she is able to find a spice for every character in the story.

Turmeric the auspicious spice

Lalita, a young woman abused by her husband seeks warmth and aid from Tilo, who while being conscious of the violence does not directly acknowledge it but attempts to help Lalita by giving her haldi or turmeric. In the book, turmeric provides Lalita with the power of bravery and fortitude she desperately needs as she contemplates taking her own life. Turmeric is gendered in Sanskrit; it is feminized as Gauri (to make fair), Jayanti (victory over sickness), and Lakshmi (prosperity). Turmeric is also linked to the fertility goddess Uma. It symbolizes female power and is thought to cleanse sin and negativity. When Lalita eventually escapes her husband and runs away from a life of marital abuse and violence, she transforms into a representation of female power.

Tilo later also gives Lalita fennel or saunf which is an equalizer. In mythology, the sage Vashista eats fennel after swallowing the demon Illwal to ensure that he won’t reappear. This symbolizes Lalita’s triumph over her tormentor.

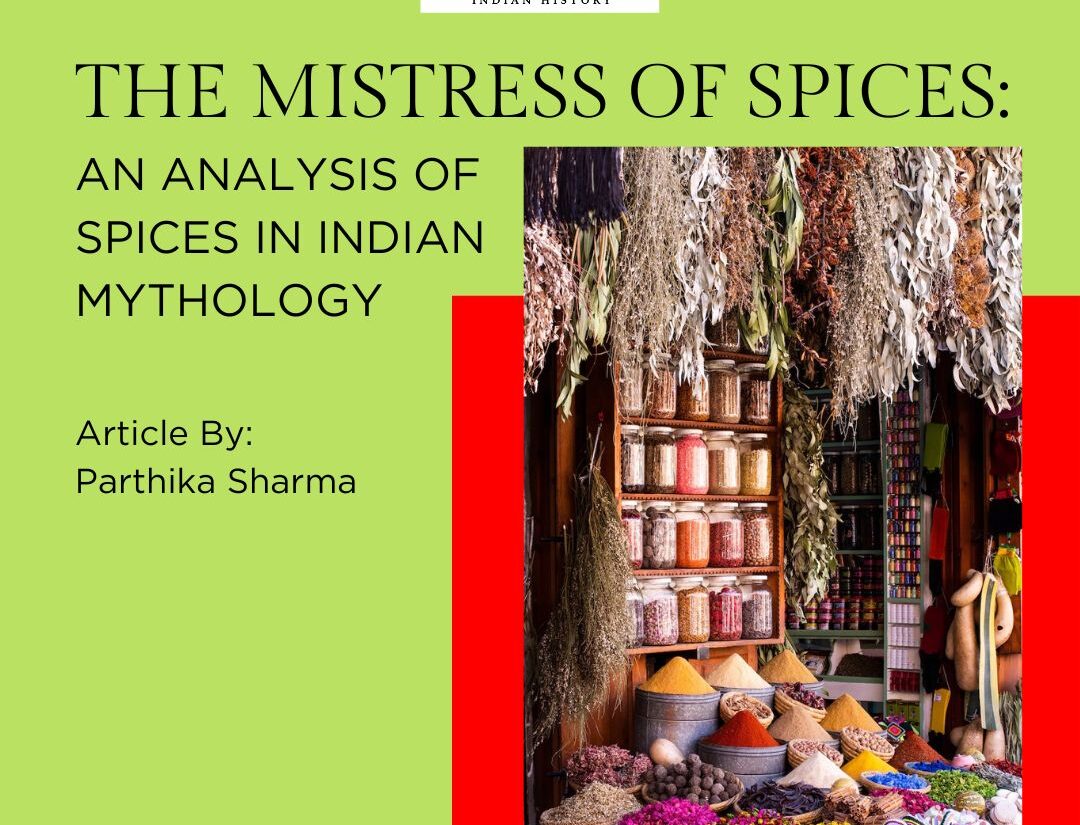

Spice Market

She offers Jagjit, a youngster who has fallen into a disastrous crowd manjistha, to soothe his thoughts. It is described by the Indian sage and physician Charaka as a “rejuvenating herb” with strong detoxifying properties. Tilo is attempting to purge Jagjit’s confidants through this Indian Spice. The Aitareya Aranyaka, written during the Vedic era, contains the herb’s oldest allusions. It played a significant role in ancient Indian traditional religious ceremonies, particularly the sacred thread ceremony known as “Upanayana Samskara.” Tilo desires Jagjit to be reborn as a good person.

With the aid of the magical powers of the spice Kalojire, she tries to shield the driver Haroun from a vision of him in a gory bloody mess. Tilo believes that Kalojire can ward off the evil eye because she associates it with the dark planet Ketu. Ketu is thought to heal the effects of snakebites and illnesses brought on by poisons, offer prosperity to the devotee’s family, and protect against both. He grants good health, fortune and cattle to his devotees.

When it isn’t sufficient, she turns to red chillies, which she claims contain lanka. Lanka red chilies, she claims, are a purifier of evil when all else fails. She is advised not to unleash Lanka’s furious power on the city. This is reminiscent of the legend of Hanuman setting Lanka ablaze and turning it into ash; Oakland, which was later destroyed by an earthquake, would soon share this fate.

Tilo’s story, which begins with sesame, concludes with the magical powers of makaradwaj. Going against the spice’s wishes, Tilo pursues a relationship with Raven. She fears she will be sent back and wants to spend a good day with Raven. She makes herself appear younger by using Makaradwaj. Makaradwaj, a rejuvenator, was given by Ashwini Kumars, twin physicians of the gods, to Dhanwantari to make him foremost among healers. Divakaruni refers to Makardhwaj as the conqueror of time. Tilo, who, like many other women, suffered entrapment by what was chosen for them by others, finally take on the role of the seeker. She risks her magical powers to use her skills for herself.

In the novel, we are introduced to several other Indian spices and their varied uses Tilo- aadrak or ginger for courage and fortitude, jeera or cumin for fending off evil, dalchini or cinnamon for friendship, hing or asafoetida as the antidote of love potion, kamal or lotus root for love along with pepper to make people tell truth. These uses are at par with the ancient therapy method of Ayurveda which is deeply associated with Indian culture.

Spices have unimaginable relevance in creating Indian food, in Indian medicinal therapy, and in Indian culture. The Mistress of Spices serves as a conduit for spreading knowledge about the vitality of Indian spices and herbs as well as their therapeutic properties. More importantly, spices represent tradition and the novel is also about breaking traditions that do not serve one’s purpose. Only when Tilo refuses to submit to the spices and takes charge of her destiny does she truly become the mistress. She becomes Maya- the power that keeps this imperfect world going.

The Indian Masaledani

In conclusion, spices are inseparable from what India is in essence- be it cuisine, tales, medicine, festivities, customs, or even ‘masala’ movies. Ayurveda, the Indian healthcare system, is beginning to be adopted all over the world as the traditional medical method gains popularity. Spices are the primary ingredients of Ayurvedic formulation used for antipyretic purposes namely, Sudarshan Churna and many more. India is one of the leading exporters in the world and produces more than two million tonnes of spices annually, making up more than 40% of the world’s spice trade. Out of 109 spices recognized by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) more than 52–60 spice crops are grown and exported from India. From the kitchen masaledani to the trendy culinary world, the aroma of spices has weaved Indian history into what it is today.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

- Simoons, Frederick J. Plants of life, plants of death. Univ of Wisconsin Press, 1998.

- Singh, Jayshree. “Spices’ Action with Internal World–The Mistress of Spices by Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni.” International Journal of English Language, Literature and Humanities (2019).

- Afzal, Thahiya, and Kalyani Mathivanan. “The Confluence of Spices: Paradigms of Identity and Self Discovery in Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s The Mistress of Spices.“

- Narwal, Anju, and Gakhar Ashima. “Peregrination of Culture through Spices & Herbs: A Study of Divakaruni’s Mistress of Spices.” International Journal of Creative Research Thought(2021).

- Kumari, P. Prasanna. Diasporic Consciousness in the select novels of Chitra anarjee Divakaruni. Lulu. com, 2018.

- Jona, P. Helan, and Cheryl Davis. “Magical Role of Spices in Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s The Mistress of Spices.” Think India Journal 22, no. 3 (2019): 410-416.

- Divakaruni, Chitra. The Mistress Of Spices: Shortlisted for the Women’s Prize. Random House, 2010.

- Pandey, Rajbali. “Hindu saṁskāras: a socio-religious study of the Hindu sacraments.” (1949).

Belouaer, Ichrak. “Myth and Magical Realism in Cheetra Banarjee Divakaruni’s The Mistress of Spices.” PhD diss., University Kasdi Merbah Ouargla, 2020.