The Power of Time: Evolving meanings of time in the Mughal Empire

- enrouteI

- September 12, 2024

How did the Mughals quantify time? What did it mean to each Mughal ruler? The concept of time in the Islamic world was a topic of discussion which led to philosophical debates and dedicated introspection on its nature, whether it can be measured or it is more poetic in its essence. The spiritual aspects of time are more pronounced through the teachings of Sufism, the mystic nature of time presents it as an entity and a tool of god, and these teachings also permeated in India through the Chishti order of Sufism.

In the fifteenth century India, Mughal rule had influenced every facet of human condition in India, specifically bringing along their technological learning and advancements to Hindustan. Through meticulous research, we get to know about the meaning and significance of time and its evolution during different eras as the Mughal ‘padshahs’ succeed one another. The structure and function of time are important in defining the cultural advancements of the era, with its ever-changing artistic symbolisms during the reigns of different rulers.

For Zahir ud-din Muhammad Babur, the founder of the Mughal era in India, technological advancements became the major source of attention. He was fond of different streams of sciences, ranging from horticulture to botany. In his memoir, Baburnama, written in Turkish Chagatai, he describes this versatile world of science in great detail. He began writing his memoir at the age of twelve and continued until the years before his death.

When he came to India in 1526, Babur has mentioned the usage of water clocks which were used by natives of the country to measure time and quantify it ad per the levels of water. He has described it as memoir Baburnama, “…the town people here employ a timekeeper called ghariyalli, who sounds a large brass plate bell hanging at a high place in the centre of the town to mark each pahar of the day. A day and night have four paharseach. The ghariyalli’s used a water timepiece, a clepsydra, to measure and announce a ghari.” One of the most ancient systems to measure time is the usage of – water clocks and sundials. Babur’s accounts describe the usage of water clocks in town squares along with the usage of traditional sundials, which influenced the construction of Jantar Mantar in Jaipur by Rajput Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh, one of the biggest sundials in the world and nineteen astronomical tools.

As the time went on, the developments in science and technology became even more pronounced during the reigns of Humayun and Akbar. For Humayun, time became the signifier of destiny and carried deeper connotations beyond ‘good’ and ‘bad’. It became an entity that defined royal superstitions, Humayun had employed a team of experts and philosophers to predict the holy time periods or ‘shubh mahurat’ and every task was defined through those periods. Humayun’s dedicated interest in astrology and astronomy was fortified through the existence of ‘janam patri’ for Akbar. The celestial globes and astrolabes were already produced during Humayun’s reign however the surviving pieces belong to the reign of his successors, and they were largely produced in Lahore under the guidance of Diya’ al-Din Muhammad bin Qa’im Muhammad (members of family whose four generations were involved in producing scientific instruments). The founder of the workshop, Shaykh Allahdad Asturlabi Humayuni Lahuri (formerly in the library of Nawab Sir Salar Jung Bahadur in Hyderabdad). who has been presumed to be an active metalworker and producer of celestial globes and astrolabes during the reign of Humayun.

A highly important Mughal planispheric astrolabe, signed by Diya al-din Ibn Muhammad Qa’im, India, Lahore, 1657 CE, Engraved Brass, Sothebys.

Furthermore, technological innovation could also be seen in Lahore during Akbar and Jahangir’s reign with the production of astrolabes. One of the visual examples that show the active use of astrolabe is seen in the painting Noah’s ark by Miskin, painted in 1590, it shows the astrolabe held by one of the persons who is part of the ship’s crew.

Noah’s Ark, ca. 1590, Miskin, Mughal dynasty Akbar(r. 1556 – 1605), Color and gold on paper, National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Museum, Washington D.C. , Detail from the painting focusing on the astrolabe

This interest in scientific theories became more syncretic and political during Akbar’s reign, with the presence of Indo-Persian Sufi polymath Sayyed Mir Fathullah Shirazi, an inventor and a close confidant of Akbar. He was instrumental in the creation of the calendar, which was defined by different periods of harvest in India. Therefore, time became more political in nature and it also defined the periods of abundance and its absence. In many way, the quantification of time and its division in different periods transformed people’s perception of their own life and goals.It also gave the false hope of control which would grip the farmers as they timed the harvest of crops with a greater accuracy, as this new calendar known as phashali shon and it coincided with the agricultural cycles, hence helping in collecting taxes in a more defined manner.

The reign of Jahangir and the influx of travellers in his court, the presence of Thomas Roe specifically, brought the western world closer into the royal quarters of Mughal nobility. This was not a mere visit by one of the merchants from the western world, rather a more formal introduction of English royalty with the presence of a representative, a diplomat in the corporeal form of Thomas Roe. He brought various gifts for the Padshah of the biggest economies in the 17th century world, including hourglasses, prints and paintings from Europe and Middle East, henceforth introducing Jahangir to novelties of global developments in humanism and European industrial progression.

In the Mughal empire, the role of art and culture was an extension of the ruler’s belief systems, bringing forth a facet of identity that defined the intellectual prowess of their reign. While Akbar focused on the syncretic nature of texts, under his spiritual program of Din-i-illahi (divine monotheism), encouraging tolerance of different religious ideologies leading to illumination of Hindu texts like Ramayana and Mahabharata alongside cementing the legitimacy of his ancestors through the texts of Baburnama and Akbarnama, the cultural ethos of the Mughal court touched new heights during Jaangir’s reign. Art Historian Dr. Mika Natif notes that the presence of European objects became more pronounced and also helped to understand the Occidental aspects of Mughal art and culture.

Jahangir, being a humanist and a naturalist, supported the visual arts to enter its golden period by encouraging the cross-pollination of varied visual vocabularies. The aspects of Mughal occidentalism are seen in the European objects in the Mughal paintings, which are not simply placed in the visual articulation, but Dr.Natif points out that they are ‘Mughalised’ to symbolise deeper meanings and views of the soveriegn. This is manifested in the allegorical paintings of Jahangir, where the semiotics presents the politics of power and visuals; specifically seen in the paintings – Darbar of Jahangir, by Abu’l Hasan, Jahangir Holding a Globe by Bichitr, and Jahangir preferring Sufi Shaikh over kings by Bichitr, all the paintings have some connection with the idea of time and its various connotations.

Darbar of Jahangir, by Abu’l Hasan, ca. 1615, album folio, right side of a double-page composition, Mughal India. Ink, opaque watercolor and gold on paper. Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C.

In the painting ‘Darbar of Jahangir’, Abu’l Hasan has presented the globe as a manifestation of Islamicate, European, and Mongol traditions of Diplomatic gifts, knowledge and power. It also alludes to the terrestrial and celestial globes that were produced by Mughal artisans, and were used as part of ceremonial gift giving in Mongol culture. Furthermore, it presents the emperor garbed in lavish attire gently resting his feet on the globe. Dr. Natif points out that the globe has the correct cartographic details painted on it and the artist has deliberately painted a keyhole right below the emperor’s little toe placing it on the Indian subcontinent. One of the interesting details noted by Dr. Natif is the presence of the keyhole, implying that the globe could be a decorative box containing a mechanical device inside of it – presumably a clock or an automaton. Therefore, the presence of a globe with a keyhole and its allusion to being a clock connotes the power of Jahangir who holds the key to the most important aspects of an era, intensively focusing on his control over the maritime trade routes, hence cementing his role as a supreme ruler of the era and a provider to the common folk of his empire.

Bichitr. Shaykh Mu’in al-Din Chishti Holding a Globe, detail of miniature from Minto Album, c. 1610-18, India, Ink, opaque watercolour and gold on paper, Chester Beatty Library, Dublin

Jahangir Holding a Globe, by Bichitr, ca. 1614–18, perhaps Ajmer, Mughal India. Ink, opaque watercolour and gold on paper. Chester Beatty Library, Dublin

More allegorical portraits of Jahangir that have correlations with time and its subtext are presented in the paintings by Bichitr. In the painting Jahangir Holding a Globe, the emperor is holding the globe in his right hand and the key is inserted in the keyhole, and the painting is facing the portrait painting of Sufi Shaikh Salim Chishti who is holding a similar celestial globe which is crowned and has a key placed on it. The symbolisms of celestial globes are connected to the culture of Mongols who used the celestial globes for astrological and astronomical purposes. This tradition was followed by Humayun who devotedly followed astrology, and these celestial globes were produced during the reigns of Akbar and Jahangir. The celestial globes are similar to astrolabes, and they were used by Islamic philosophers and astronomers, both globes and astrolabes were traditional methods to tell time for daily prayers and were also used by the travellers for navigation.

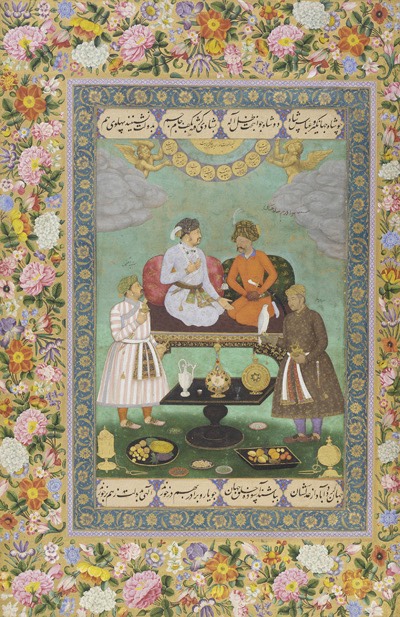

The more direct symbolism of time and power is seen in the painting by Bichitr – Jahangir preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings, where the throne of Jahangir is depicted as an hourglass, which in itself signifies his long and fruitful reign.

(Left image) Jahangir (d.1627) preferring Sufi shaikhs over King James I of England; by Bichitr, earlier 1620’s, Watercolours and gold on paper, National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian, Washington D.C., (Right image) Matthias Zoller, Hourglass, Augsburg 1671, National Museum, Warsaw.

Presented in a delicate manner with a masterful fineness, are two angels/putti playing at the base of the hourglass who have engraved in Persian the following message –

“Allah is great. O Shah may the span of your reign be a thousand years”.

Dr. Ursula Weekes points out the connections between time and power, and how Jahangir has used these allegorical paintings to cement his stature as a celebrated ruler, and the time in itself becomes an entity that signifies power. The painting also suggests the ‘Mughalisation’ of European objects, in this scenario the hourglass or time is the luxury and power, mostly given as a gift to Jahangir, as it bears resemblance to the hourglass made by Matthias Zoller at Augsburg in 1671. However, the appearance of the hourglass is more in keeping with the visual semantics of Mughal painting tradition and could also have been reference from the hourglass made at the court by one of the leading European goldsmith William Leedes, who has been employed by Akbar in the 16th century.

Jahangir Entertains Shah Abbas from the St. Petersburg Album 1620; borders 1746-47, Bishandas, Opaque watercolour, gold and ink on paper, National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Museum, Washington D.C.

Another hidden symbol of time can be seen in the presence of an automaton which is held by Jahangir’s courtier, Shah Alam in the painting by Bishandas, detail of Khan Alam holding a European automaton of Diana and the Stag, in the painting Jahangir entertaining Shah Abbas. This is again related to the European fascination with quantification of time, and in both the paintings Jahangir sits outside the realms of quantifiable time, henceforth pointing towards the divine nature of royalty. The concepts of time in Islamic astronomy and astrology are multifaceted and hold multiple perspectives which stand in contrast to the sing-point mathematical perspective of European time standards.

Conclusion:

The visual examples along with textual sources illustrate a complex and layered relationship between the Mughal culture and the concept of ‘time’. The intellectual meanings of time and its connection to the timelessness of their majestic power is showcased in their practices, policies and their vast visual heritage. Traversing beyond the mere quantification of time to track hours and days, every aspect of their heritage symbolised time as an era and as a tool, henceforth masterfully painting a powerful picture of nobility that was underpinned by the politics of imagery and idioms.

Bibliography:

Sowing Seeds of Thought. “Was Indian Time-Keeping Technique Primitive?” Sowing Seeds of Thought, 2 June 2011, http://sowingseedsofthought.blogspot.com/2011/06/was-indian-time-keeping-technique.html.

StudySmarter. “Mughal Astronomy.” StudySmarter, https://www.studysmarter.co.uk/explanations/history/the-mughal-empire/mughal-astronomy/.

The British Academy. “A Closer Look at the Mughal Emperor Jahangir Depicted with an Hourglass on His Throne.” The British Academy, https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/blog/closer-look-mughal-emperor-jahangir-depicted-hourglass-throne/.

Self Study History. “Mughal Science and Technology.” Self Study History, 27 Jan. 2015, https://selfstudyhistory.com/2015/01/27/mughal-science-and-technology/.

Mackenzie, John. “The Astronomical Mughal.” Open Magazine, 10 Sept. 2020, https://openthemagazine.com/art-culture/the-astronomical-mughal/.

Mills, David. “Finding and Founding: Blog Three – The Travels of an Astrolabe.” History of Science Museum, University of Oxford, https://www.hsm.ox.ac.uk/finding-and-founding-blog-three-the-travels-of-an-astrolabe-1.

“Fath Allah Shirazi.” Encyclopædia Iranica, https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/fath-allah-sirazi.

“Fathullah Shirazi.” Wikipedia, https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fathullah_Shirazi.

“Celestial Globe.” Encyclopædia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/science/celestial-globe.

“A Planispheric Astrolabe by Diya’ al-Din al-Kashi.” Christie’s, https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-5985212#:~:text=Diya’%20al%2DDin%20was%20a,planispheric%20astrolabes%20and%20celestial%20globes.

“A Highly Important Royal Mughal Planispheric Astrolabe.” Sotheby’s,

https://www.sothebys.com/en/buy/auction/2020/arts-of-the-islamic-world-india-including-fine-rugs-and-carpets/a-highly-important-royal-mughal-planispheric.

Natif, Mika.Mughal Occidentalism: Artistic Encounters Between Europe and Asia at the Courts of India, 1580-1630. Brill, 18 Aug. 2018.

- September 27, 2024

- 9 Min Read

- September 11, 2024

- 12 Min Read