Britishers ruled India for approximately 200 years, but the seeds of this rule were sown a few years before that. With the battle of Plassey in 1757, the British East India Company got involved in the internal politics of Indian princely states and fought openly with one of them. The Battle of Plassey and the Battle of Buxar were instrumental in showcasing the might of British artillery, but the real power was cemented with the revolt of 1857. The Indian revolt of 1857 is known by various names, such as the Sepoy mutiny and the Indian rebellion of 1857. This Indian rebellion witnessed the rise of feelings of mistrust and annoyance towards British rule, and several Indian princely states fought in this war at various stages. The revolt of 1857, though fought on a wider scale, was eventually quelled by the British, and they imposed strict measures to suppress future revolts. It was well documented, and almost every British newspaper covered it. The sources to know about the turn of events, timeline, and causes and effects are all known through the official documents and diaries of British officials and the photographs that were taken at the time of the war.

Felice Beato

(Source- Unknown photographer, 1866 Albumen silver print, Old Japan Picture Library)

The revolt of 1857 began in Meerut with the military mutiny against their British superiors. There were various underlying causes for the dissent amongst the Indians towards Britishers, such as their interference in Indian social and religious matters and bringing in various reformatory laws and regulations. The British policy of expansion witnessed their annexation of various princely states such as Satara, Jhansi, Sambhalpur, and Awadh, and this created an air of mistrust amongst their residents. Their soldiers, too, felt betrayed. They suffered because of the racial approach of the British officials. Though there were numerous causes for the revolt, the immediate cause was the introduction of the Bess Enfield rifle. There were rumours that the cartridge of the rifle was made of pig or cow fat, which was hurtful to the religious traditions of Hindus and Muslims. This made the soldiers express their problem with the rifle. The problem was ignored by the British officials. This incident triggered a chain of events that culminated in the Indian rebellion of 1857.

The Chutter Manzil, showcases the damage caused by the British siege

(Source- Albumen print, 1858, The Wellcome Collection, London)

The revolt of 1857

After the hanging of the rebel soldier, Mangal Pandey, in Meerut, the soldiers from his regiment revolted. The revolt spread over the regions of Kanpur, Lucknow, Jhansi, Gwalior, and Awadh. Various names shine through the tales of the revolt of 1857; prominent amongst them are Begum Hazrat Mahal of Awadh, Nana Saheb, Rani Lakshmi Bai from Jhansi, and Kunwar Singh from Bihar. Though the rebellion was widespread, it lacked a powerful leader who could lead all the states, and it was disorganised. After an initial setback, the British soldiers captured the princely states, and the offenders were dealt extreme punishments. Though unsuccessful and short-lived, this Indian rebellion was significant for various reasons, such as highlighting the rising dissent against the British and also the nature of its documentation. The Indian revolt of 1857 is one of the first wars to be captured by the camera lens. There are colonial Indian photographs that capture the war and its aftermath. One of its leading photographers was Felice Beato.

Pioneer of war photography: Felice Beato

Felice Beato was born in Venice, Italy, in 1832. His family shifted to Corfu when he was young. Hence, he became a British Italian citizen. He met British photographer James Robinson during a visit to Malta in 1850. Robinson introduced him to photography and employed him. Felice Beato was a part of the ‘Robertson, Beato, and Co.’ that worked in Greece and Egypt. Felice Beato later turned to war photography. In a career spanning over five decades, he photographed places related to wars in India, China, Japan, Korea, and Burma. He came to be known as the father of Yokohama photography in Japan and was the most famous western photographer in Asia.

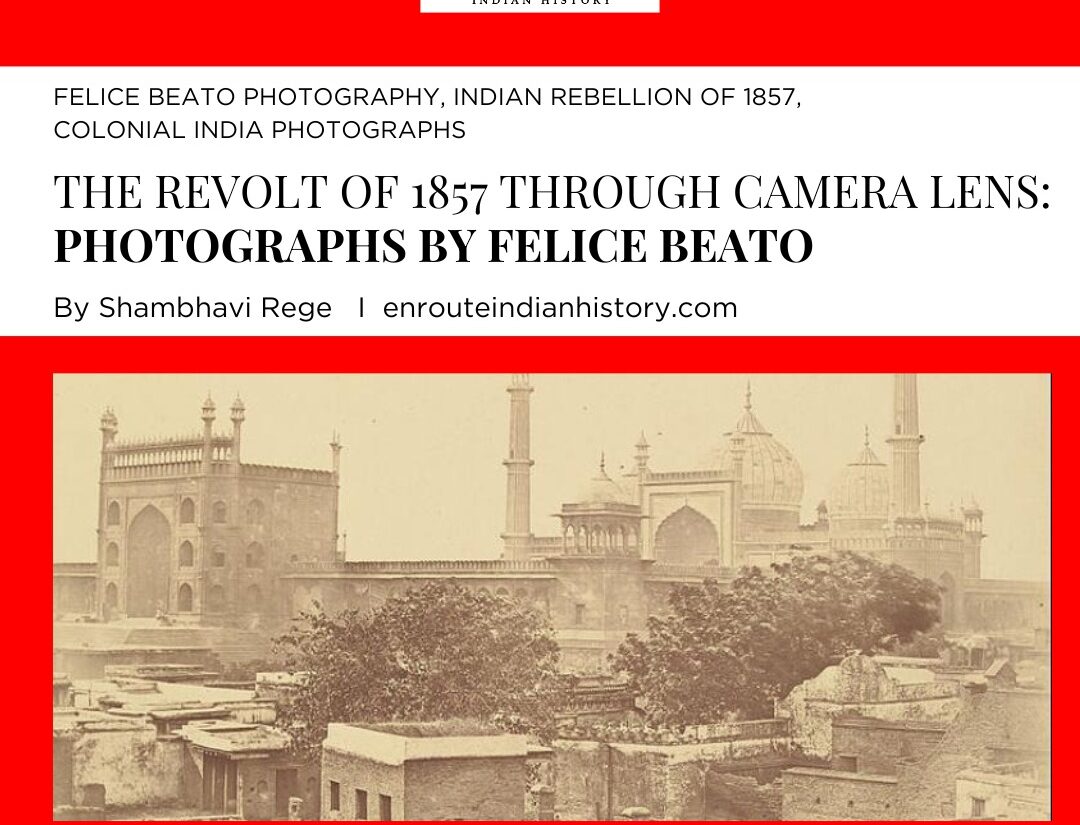

Entrance to the Jama Masjid in Delhi

(Source- J Paul Getty Museum)

Felice Beato captured photographs at a time when the process of photography was complex and required lots of acumen. His main equipment consisted of a large box camera that used 10 by 12 inch plates. The resulting albumen glass plate negatives were printed on silver chloride paper. Photographs taken were limited by the long exposure time that was required for the camera plates to record light. And were unable to capture movement. It was a laborious process. Some of the photographs occasionally resulted in blurred figures and flags. Under such circumstances, Felice Beato managed to capture the war scenes in the Crimean War during 1855–56, the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the Second Opium War in 1860, and the American Expedition to Korea in 1871. Out of this, Felice Beato’s photography of the revolt of 1857 in India gained him wider recognition in the British audience. The colonial India photographs captured by him presented the unpleasant scenes of the rebellion and its aftermath.

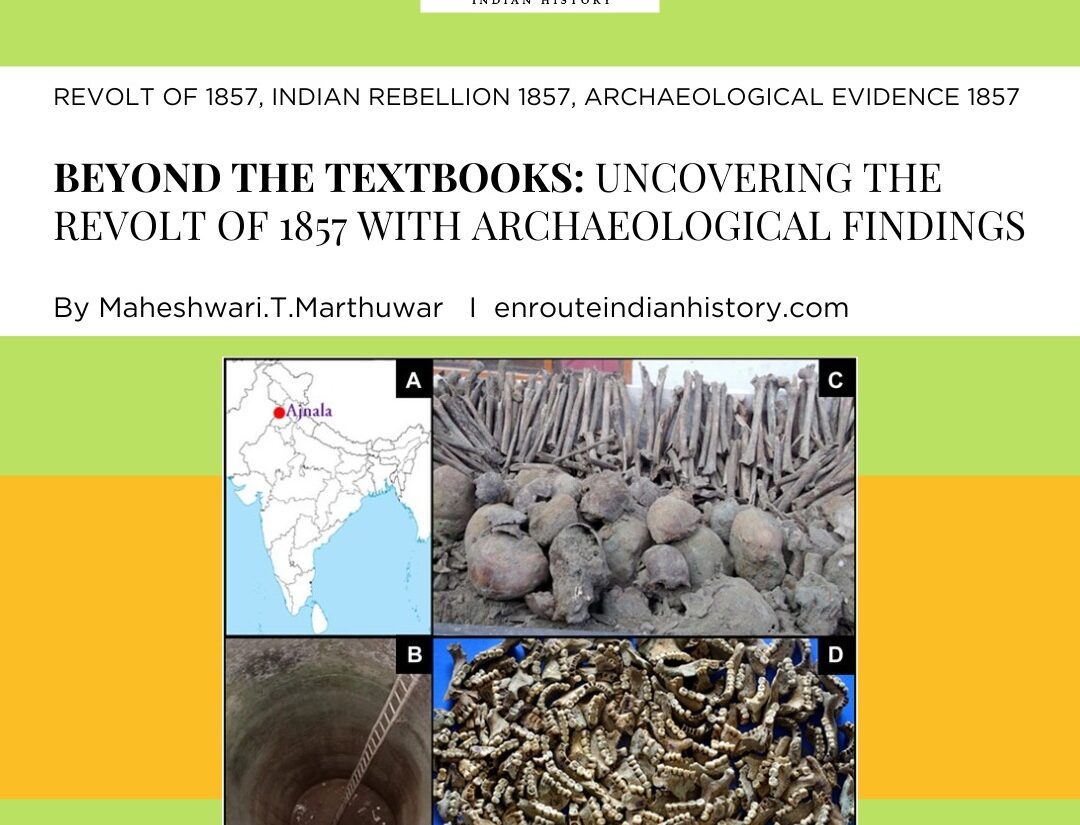

Courtyard of the Sikandar bagh

(Source- Albumen silver print, 1857

©The David Collection

War photography of the revolt of 1857

Photography arrived in India soon after 1839. The colonial India photographs were seen as a means of documentation by the British officials and governors. These photographs provide a glimpse into the unjust British occupation of India and its effects on the social, religious, economic, and political fabric of the country. Photographs captured by Felice Beato present a more harrowing picture. It was in February or March of 1858 that Felice Beato arrived in Calcutta. Though the exact date of his arrival in India is unclear, he is said to have addressed a Bengal photographic society on February 17, 1858. He was commissioned by the War office in London to make documentary photographs of the war. Felice Beato reached Lucknow in March, within a few weeks of the fall of the city in the hands of British forces under Sir Colin Campbell. Lucknow had witnessed two sieges before it fell, from September 1857 to March 1858. The city was in ruins, its structures bearing the result of the canons and bullets that were fired during the Indian rebellion.

Jantar Mantar near Delhi

(Source- J Paul Getty Museum)

After being placed in this city by British officer Francis Cornwallis Maude, Felice Beato travelled all over the city in a full caravan of Indian workers who helped him set up his camera and looked after his travels. He travelled to search the sites for photographs and photographed over 60 places. In Sikandar Bagh, one of the prominent centres of the Indian rebellion in Lucknow, photos were taken months after the event. The interred remains of Indian rebels who were buried there were said to have been exhumed and arranged on the orders of Felice Beato. The scenes were arranged in such a way to highlight the ghastly events that they are also interpreted as a display of the British win over the rebels and the brutal suppression of the revolt of 1857. Felice Beato took help from British officials to search for the sites and record the scenes of the aftermath of the uprising. The hanging of the mutineers in Lucknow, named the ‘execution of mutineers’ of 1858, was one of his works. He captured the infamous execution scene of two Indian rebels. Though there are no established photographs, he is said to be the first person to photograph corpses. The exhibition of Lucknow photographs was displayed in Leeds in October 1858 and at the photographic society in London in 1859. He captured war photographs at Delhi, Kanpur, Amritsar, and Simla.

The execution of mutineers

(Source- Albumen print, 1858, The Wellcome Collection, London)

The signatures on the Felice Beato photography were styled as ‘Felice Antonio Beato’ and ‘Felice. A. Beato’. It was long assumed that there was one photographer who captured images in Egypt and Japan on similar timelines. But in 1983, Chantal Edel showed that it represented two brothers, Felice and Antonio Beato. Felice Beato produced images of the devastating battle and its human toll in order to provoke shock and awe in the European audience. He retired in Florence, Italy, where he died in 1909. Years later, an Australian professor named Jim Masselos came across a collection of Beato’s works. He wanted the photos in the public domain and hence travelled to India in 1997 to capture images at the exact locations. He was helped by the historian Narayani Gupta. He came up with the illustrated book ‘Beato’s Delhi: 1857 and Beyond’.

References

Harrington, Peter. “Lucknow after the Indian Mutiny .” the photographs of Felice Beato. Military Heritage , February 2005.

Willcock, Sean. “Aesthetic Bodies: Posing on sites of violence in India, 1857-1900.” History of Photography (2015): 142-159.

https://www.all-about-photo.com/photographers/photographer/1394/felice-beato

https://mapacademy.io/article/felice-beato/

https://library.brown.edu/info/collections/askb/beato/

https://sarmaya.in/spotlight/the-story-of-a-rebellion-in-5-pictures/

- May 29, 2024

- 11 Min Read

- May 29, 2024

- 14 Min Read