Sufism (Sufi) originated as a spiritual reaction against the materialism prevalent in the Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates during the early centuries of Islam (7th and 8th centuries CE). According to prophetic tradition, Islam encompasses three dimensions: “Islam,” referring to submission as prescribed by jurists; “Iman,” faith as preached by theologians; and “Ihsan,” the pursuit of beauty through acts of worship and spiritual discipline practised by Sufis. The primary goal of the Sufis is to attain nearness to a compassionate and loving God through prayers, meditation, and spiritual exercises, which may not always conform to orthodox interpretations.

Influential figures such as Bayazid Bustami, Rabi’a al-Adawiyya, and Hasan al-Basri lived modest, ascetic lives, seeking union with God through meditation and spiritual practices. These early Muslim mystics, often charismatic leaders, eventually organised into “silsilas” or spiritual orders, which further diversified. Typically, Sufis initially rejected worldly attachments, advocating introspection, spiritual contemplation beyond ritualistic prayers, solitude for meditation, and itinerant lifestyles as dervishes in both Muslim and partially Islamized regions. They claimed personal experiences affirming the truth of Islam, God’s compassion, and the righteousness of the Prophet’s path. As religious guides, Sufis aimed to lead Muslims by example, tolerating human frailties while also endeavouring to attract non-Muslims to Islam. First, followers or guests were guided by the living Sufi master at his hospice ( khanqah or jamatkhana). Subsequently, the shrines (dargahs) of earlier generations of Sufis gained prominence and developed into pilgrimage sites. Eventually, these sites carved out a whole sacred geography of Sufism known as wilayat, which involved intense conflict and rivalry over territory, adherents, and resources.

Despite facing opposition from various quarters, Sufism continues to thrive as a dynamic movement, attracting followers from diverse segments of society: from the rural and urban poor to outlaws, politicians, and government officials who visit Sufi shrines to offer ritualistic chadars and prayers. People have been drawn to the Sufis because of their apparent mystical abilities and capacity for local dialect communication, with many of their followers seeking blessings and spiritual favours.

Qawwali and other forms of devotional music play a central role in Sufi practices. Qawwālī is a form of Sufi music in India and Pakistan. Contrary to the widespread belief that Amir Khusrau invented qawwali, qawwali probably only emerged as a distinct genre in the early eighteenth century. Before this period, qawwals, performers of qawwali, engaged in various genres, including qaul, which means “saying” that expresses a fundamental Sufi principle rooted in a saying (hadis) attributed to Prophet Muhammad himself, establishing the concept of spiritual succession in Sufism.

(wanderon.in – view of the Hazrat Nizamuddin Dargah)

(Ramesh Lalwani, Wikimedia Commons – Basant celebrations at Hazrat Nizamuddin Dargah through qawwali)

One of the most renowned qauls is “Man Kunto Maula,” which combines Arabic and Persian and asserts that accepting Prophet Muhammad as master also implies accepting Hazrat ‘Ali, the progenitor of all Sufi silsilas. At the Hazrat Nizamuddin Dargah, no qawwali starts in any other way than with this qual. Hazrat Nizamuddin Dargah is widely acknowledged as the place where khānaqāhī qawwālī, a form of mystical music performed in Sufi shrines for the purpose of zikr (remembrance of Allah), originated within the Chishti Sufi order. This enduring tradition remains vibrant today, with khānaqāhī qawwāls finding inspiration from the sacred tomb (rauzā) of Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya and his esteemed disciple, Amir Khusrau. Amir Khusrau, revered as the founding figure of khānaqāhī qawwālī, has profoundly influenced both the spiritual and musical practices associated with Dargah Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya.

The structural underpinnings of khānaqāhī qawwālī are largely attributed to Amir Khusrau (1253–1325). Legend has it that he gathered twelve boys, known as the Qawwāl Bachche, whom he trained extensively in the art of khānaqāhī qawwālī, imparting to them the essential principles of music, poetry, and the codes of conduct necessary for their interactions among Sufis. In addition to daily qawwālī performances at the Nizamuddin dargāh, there are special gatherings known as mahfil-esamā’, organised on occasions, and qawwālī sessions held on Thursday and Friday evenings, featuring renowned qawwāls such as Hamsar Hayat Nizami, Ghulam Waris Nizami, and Chand Nizami. The most significant qawwālī events are celebrated during festivals such as the ‘urs (death anniversary) of saints, the ghusal śarīf (holy bath) ceremony at Hazrat Nizamuddin’s grave on his birthday (jaśn-e-wilādat), and the birth and death anniversaries of revered figures like Hazrat ‘Ali. However, during larger Thursday and Friday qawwālī sessions attended by numerous tourists and pilgrims, performances typically begin with popular texts like Bhar Do Jholi rather than the Man Kunto Maula. This distinction between public dargāh performances and more private mahfil-e-samā’ gatherings may highlight the deeper spiritual and Sufi-oriented nature of mahfil-e-samā’.

(Wikimedia Commons – Guler painting showing an imaginary meeting of Sufi saints (Baba Farid, Khawaja Qutub-ud-din, Hazrat Muin-ud-Din, Hazrat Dastgir, Abn Ali Kalandar, and Khawaja Nizamuddin Aulia)

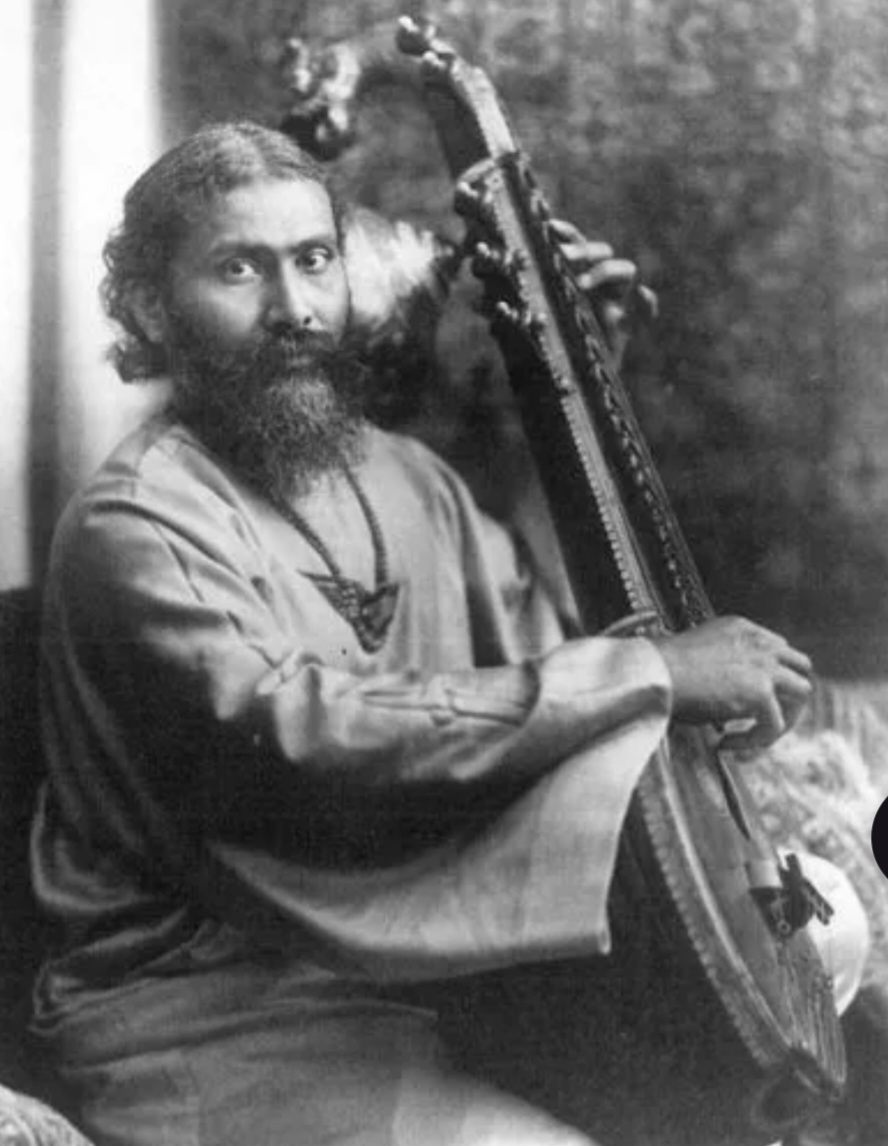

In the context of qawwālī, samā’ serves as the foundational experience from which the art form emerged. In the Sufi tradition, samā’ signifies spiritual listening, especially to music, with the intention of attaining a state of grace or ecstasy. Alternatively, it is viewed as a form of meditation, a deep introspective journey, or as Sufis describe it, a means to “nourish the soul”. Hazrat Inayat Khan, a saint of the 19th-20th century whose tomb (rauzā) lies near the Nizamuddin dargāh, delineated three stages of wajd (ecstasy): first, union with an earthly ideal, such as a spiritual guide; second, union with the beauty of the ideal’s character, irrespective of form; and third, union with God, described as the “divine Beloved.”

(Wikimedia Commons – A portrait of Hazrat Inayat Khan)

There is also the Dargah Hazrat Qutubuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki in Mehrauli. Bakhtiyar Kaki, the master of Nizamuddin’s spiritual mentor, is often overshadowed by the latter. However, Bakhtiyar Kaki’s shrine remains beloved among locals, drawing hundreds of visitors daily who pay homage to the Sufi mystic regardless of their religious affiliation. During a gathering of sama, he heard a verse by Hazrat Ahmad Jam that deeply moved him: “Those who are slain by the dagger of surrender and delight receive a new life from the Unseen.” Hazrat Khwaja Bakhtiyar Kaki became so enraptured and inspired by this verse that he began reciting it continuously in a state of ecstasy, ultimately passing away while immersed in this profound spiritual state. For three consecutive days, he remained absorbed in Wajd (ecstasy) until he breathed his last on the fourth day, which was the 14th of Rabi-ul-Awwal 633 A.H. Due to the extraordinary circumstances of his death, he is revered as “Shahid-e-Mohabbat” or the Martyr of Divine Love.

(Zuck28, Wikimedia Commons – the annual Urs celebration at Dargah Hazrat Qutubuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki)

The rich tradition of Punjabi Sufi songs and poetry somewhat mirrors the qawwālī tradition. Its origins can be traced back to the devotional poetry of Baba Farid (1173-1265), the chief disciple of Khwaja Qutbuddin Bakhtiar Kaki, who established the first Sufi center in Delhi in 1221. This poetic tradition reached its pinnacle in the mystical verses of Shah Hussein (1538-1599) and Bulle Shah (1680-1757), whose kafi (a lyrical genre) have been sung by Punjabis of all faiths for centuries. Similar to qawwālī, the performers of Punjabi Sufi music include a network of semi-professional singers who are primarily locally renowned, alongside a few highly sought-after artists known for their stage performances. Notable figures in this realm include Abida Parveen of Pakistan, renowned for her interpretations of Sufi music in Urdu and Sindhi, as well as Hans Raj Hans and the Wadali Brothers.

The recent surge of interest in Sufi music has not only spotlighted traditional performers, but also introduced a new wave of artists exploring unique expressions of self-described Sufi music. This trend includes modernized versions of film qawwālīs, which have experienced a resurgence in North Indian music traditions. While these contemporary forms vary widely in style and presentation, they are unified by their explicit Sufi orientation, conveyed through lyrical content, accompanying visuals, or promotional narratives. While historical Sufi culture was deeply rooted in shrine traditions and subaltern contexts, today’s Sufi music scene reflects a more mainstream phenomenon, often performed at high-profile events attended by urban elites.

CITATIONS

- GRAVES, THOMAS,ANTHONY (2024) From Separation to Union: Musical Emotion and Qawwali at the Shrine of Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/15586/

- Zuberi, I. (n.d.). Art, Artists & Patronage: Qawwali in Hazrat Nizamuddin Basti. www.academia.edu. [online]

- Aquil, R. (2012). “Music and Related Practices in Chishti Sufìsm: Celebrations and Contestations.” Social Scientist, vol. 40, no. 3/4, pp. 17–32. JSTOR.

- Manuel, P. (2008). “North Indian Sufi Popular Music in the Age of Hindu and Muslim Fundamentalism.” Ethnomusicology, vol. 52, no. 3, 2008, pp. 378–400. JSTOR.

- https://www.khawajagharibnawaz.com/KhwajaQutbuddin.html