By Chanchal Kale

Cultural diversity truly comes alive through the rich tapestry of languages spoken around the globe, each one woven with its own unique historical, geographical, and socio-political threads. Language serves as a vibrant gateway to cultural heritage, inviting individuals to delve into the world of literature, folklore, and oral traditions that reveal deep insights into the values and experiences of different societies. It creates a stage for the celebration of cultural events, with languages playing a vital role in rituals, ceremonies, and artistic expressions. One fascinating example is the Toto Language, which illuminates the intriguing culture and social dynamics of the Toto Tribe in Bengal. This language not only connects its speakers to their past but also enables a deeper appreciation of their identity and traditions.

History of The Toto Tribe

The story of the Toto people begins in 1815, when Babu Kishan Kanta Bose, a British government employee stationed under the collector of Rangpur, first documented their existence. He stumbled upon this unique community while visiting the village of Lukepur, now known as Totopara, nestled near the border of Bengal and Bhutan. This remote village became a focal point of intrigue for officials and scholars alike, fascinated by the Totos' vibrant culture and their distinct language, which often left even local Bengali speakers scratching their heads.

However, the Totos faced a grave threat of extinction in the years following India's independence. The 1951 census revealed a mere 321 individuals residing in just 69 homes. This alarming trend spurred government action to safeguard the tribe, and on October 29, 1956, the Totos were officially recognized as a scheduled tribe under the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribes List (Modification) Order. That same year, they were designated as an isolated tribe, receiving special attention and care.

These efforts bore fruit, as the population of the Toto tribe rose significantly; by the 2001 census, their numbers had surged to 1,184, all settled in Totopara. While the tribe has demonstrated resilience through the test of time, their unique language struggles to survive, with current speakers numbering barely in the thousands. The Totos continue to hold a special place in the cultural tapestry of the region, embodying a rich heritage that deserves to be celebrated and preserved.

Toto Language

Grierson (1909) mentioned the language of Totos in Linguistic Survey of India (LSI). This classification suggests that they may have ancestral ties to Bhutan, possibly linked to Mongolian heritage. He noted that, interestingly, their language remains a closely guarded secret. Very few outsiders comprehended it, and within the community, only one member was been noted to possess partial fluency in Bangla. Grierson even included a glimpse of Toto through a partial translation of a text in his survey.

Charu Chandra Sanyal (1972) had a pioneering attempt to study the Toto language and brought out a book on them along with another one tribal language called Mech, spoken in this area.

Sanyal described the Toto language in three broad headings : numerals, out line grammar and vocabulary. Few conversational sentences were also given in his book. In the appended page, he had given the lexicals spoken by the related tribal communities for comparison. Although this work is lacking the application of modern linguistic techniques, this is the first attempt to study the aspect of Toto language.

Fast forward to more recent studies, and we find Atanu Saha from Jadavpur University delving deeper into this intriguing language. In his "Technical Report on Toto," based on immersive field research, he uncovers distinctive features of Toto. Notably, it lacks agreements in person, number, and gender, and boasts a range of nasal sounds typical of Tibeto-Burman languages, adding to its unique character.

Nasalization of the phonemes in some cases have been observed in this language. As they do not yield contrasting phonemic pairs, they have not been considered as a separate phoneme. Examples: giyãw ‘wheat’; keĩchi ‘barbar’; Tõisuwa ‘march’; oĩpowwa ‘transplant’; luã ‘husband’s elder brother’s wife’; duĩn ‘cricket’. The occurrence of nasalization is observed in the medial and final positons of the lexical items.

The Anthropological Survey of India (AnSI) highlights an inspiring yet bittersweet tale: for centuries, Toto has been preserved within this small community, surviving without a written script. Asok Kumar Mukhopadhyay, a research associate with AnSI, notes that the language thrives through the vibrant oral traditions of folklore and songs, passed down lovingly from one generation to the next. In this close-knit community, Toto remains the heartbeat of their daily communication.

However, this narrative is not without its shadows. The survey reports reveal a concerning trend—the number of fluent Toto speakers is dwindling when compared to the broader Toto population. Both researchers and community members acknowledge that the language is at risk, increasingly overshadowed by the influences of Nepali and Bengali. This poignant struggle serves as a reminder of the delicate balance between preserving cultural heritage and the relentless march of external influences.

Reasons For The Decline in Use of The Language

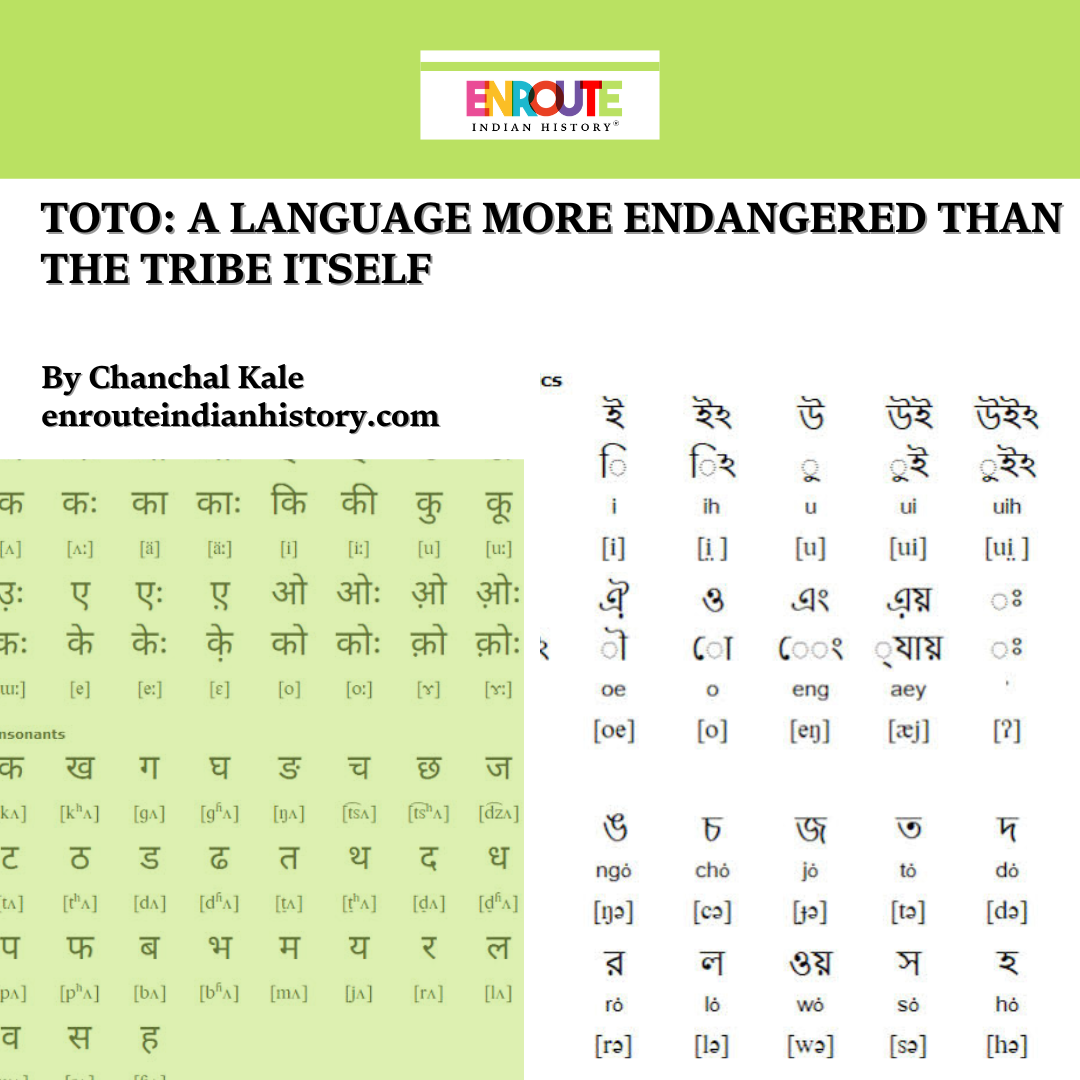

The decline of the Toto language presents a significant concern, attributable to several interconnected factors. A primary issue is the lack of a dedicated script to adequately represent the phonetic intricacies of the language. Although speakers often utilize the Bengali script for documentation, this system fails to encompass the full spectrum of sounds intrinsic to Toto.

Furthermore, a pivotal factor in the language's decline is the transition in educational mediums for Toto children, who are increasingly being instructed primarily in English or Bengali. This shift effectively side-lines their native language. The absence of institutional initiatives from government bodies or local authorities to implement Toto-language educational programs exacerbates the situation, hindering the development of linguistic pride and fluency among younger generations.

As the Toto community increasingly assimilates into the broader socio-cultural fabric, interactions predominantly occur with speakers of English and Bengali. This exposure fosters a sense of embarrassment associated with the use of their native language, as evidenced by the sentiments expressed by Mr. Bhakta Toto, a bank officer from Totopara. A disturbing trend is emerging where Toto speakers substitute native vocabulary with Bengali terms; for instance, "kaibu," signifying step, is frequently replaced with the Bengali "shiri," while "dui," indicating a veranda, is supplanted by the Bengali "baranda." Additionally, socioeconomic factors such as poverty and the lack of employment

opportunities compel many Toto individuals to migrate to metropolitan areas, further eroding their linguistic and cultural heritage. While striving for economic development is imperative, it is crucial for individuals to maintain a connection to their cultural roots.

In India, there are 75 officially recognized 'particularly vulnerable tribal groups,' yet numerous other language communities face extreme endangerment. A historical catalyst for language extinction can be traced back to the 1961 census, which determined that languages spoken by fewer than 10,000 individuals would not be classified as official languages. Dr. Pramanick of the University of Calcutta has critiqued this decision as a profound misstep and a violation of human rights, particularly concerning linguistic rights. He posits that the democratic framework often overlooks these essential rights. These dynamics paint a sobering portrait of a culture in jeopardy, underscoring the urgent need for proactive measures to preserve its linguistic heritage for future generations.

Steps Taken For The Preservation of The Language

Dr. Pramanick said that while it has been natural for languages to fade away, present-day resources and infrastructure can keep them alive. If a language dies, it is not only the death of the language but also of culture, identity, knowledge, medicine, literature, everything. With the death of a language, we lose an entire epistemology that was inherited over ages.

UNESCO has listed the Toto language as “critically endangered,” highlighting the urgent need to preserve it for future generations. Despite the challenge of lacking a dedicated script—coupled with a literacy rate of just 33.64% as reported in 2003—the Toto community has shown remarkable resilience. Remarkably, individuals have authored books and poems in their native tongue, utilizing the Bengali script.

One of the champions of this cause is Dhaniram Toto, who penned two significant works in 2012 and 2013, earning the prestigious Padma Shri in 2015 for his dedicated efforts to safeguard the Toto language and culture. He also wrote “Dhanua Totor Kathamala,” a captivating account of the Toto community, in Bengali.

Recognizing the critical need for thorough documentation, Bhakta Toto embarked on a ground-breaking project to publish a Dictionary of the Toto Language in 2023. This dictionary is set to transition the language from an exclusively oral tradition into written form, capturing its rich vocabulary. Toto words will be translated into Bengali and English and presented in Bengali script, making it accessible for community members who are more

familiar with this script, as the Toto script is still in its early stages of development.

To bring this initiative to fruition, Bhakta is collaborating with Mrinmoy Pramanick, an Assistant Professor at the University of Calcutta and Chairman of Calcutta Comparatists 1919. Their ambitious plans extend beyond the dictionary, to publish other works like “Uttal Torsa,” a Bengali novel by Dhaniram Toto, to further enrich and promote Toto culture.

These initiatives are vital for long-term language preservation. Yet, the community also emphasizes the importance of addressing immediate needs—like establishing a school dedicated to teaching the Toto language. Dr. Pramanuck also suggested that One thing we can do immediately is introduce the literatures and cultures of these languages as a separate subject at the primary school level in the concerned regions. This will be a remarkable and revolutionary policy decision. Such efforts would not only promote language learning but also instil a sense of pride in young people by encouraging them to read and explore their heritage in their own language. By nurturing the Toto language now, we can ensure it thrives well into the future.

Conclusion

Language serves as the gateway to understanding the rich tapestry of a community's culture. The Toto tribe, while recognized and protected under various Government of India schemes, faces a looming threat to its identity. Without their unique language, the very essence of what makes them who they are—their culture and history—could be lost. It raises a crucial question: what is the value of protecting the tribe if we overlook the preservation of the language and traditions that define their identity? Recognizing and safeguarding these elements is vital for the survival of the Toto tribe and its heritage.

Bibliography

1. Biswas, A. K. (2015). ETHNIC IDENTITY OF TOTO TRIBE ON CROSSROAD. The Indian Journal of Political Science, 76(4), 848–852.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/26575615

2. Chakrabarti, P & 1964 ‘Some Aspects of Toto Ethnography’ –Chattopadhyay, K. Bulletin of C.R.I. Vol.III No.2

https://www.academia.edu/30313328/A_Linguistic_Description_of_Toto_Language_Spoken_in_West_Bengal

3. Jovitasari M. and Erlangga D.T. (2023), THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN LANGUAGE AND CULTURE IN SOCIETY, Pustakailmu.id, Volume 3 (1)

4. Saha, Atanu. (2019). Technical Report on Toto, Study and Research in Endangered Languages with respect to special focus on West Bengal under XII plan, funded by University Grants Commission, Reference No. F. 63-7/ 2014 (SU-II) dated 7th September 2015. Jadavpur University, Kolkata. (Assisted by Arup Majumder, Bornini Lahiri, Dripta Piplai).

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/374558114_Fieldwork_Report_on_Toto

5. The Hindu (September 29, 2023), A DICTIONARY TO SAVE A LANGUAGE FROM EXTINCTION, Bishwanath Ghosh

https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/kolkata/a-dictionary-with-the-purpose-of-saving-a-bengal-language-from-dying/article67356202.ece/amp/

6. The Hindu ( August 1, 2014), TOTO LANGUAGE MORE ENDANGERED THAN TRIBE, Shiv Sahay Singh https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/kolkata/toto-language-more-endangered-than-tribe/article6270931.ece/amp/

7. The Straits Time (November 14, 2024), ONE LETTER AT A TIME- TOTO TRIBAL COMMUNITY IN EASTERN INDIA STRIVES TO PROTECT ITS LANGUAGE, Debarshi Dasgupta https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/south-asia/one-letter-at-a-time-toto-tribal-community-in-eastern-india-strives-to-protect-its-language