Travelling Toward Nationhood: Railways and Railway Stations in the Gandhian Freedom Struggle

- enrouteI

- June 1, 2023

Article Written By EIH Researcher And Writer

Snehal Shirpurkar

You have probably found yourself at a railway station more times than you can remember. There appears to be a strange unspoken agreement between those present at a railway station– an acknowledgement of their shared conditions of travel, of the time spent waiting. The experiences offered by the station–the hustle and bustle of porters and luggage, loud announcements, vendors and hawkers, parents trying to control their kids as they wait– are ones that we now take for granted. But these are experiences specific to time, place and have historically been fractured by identities of race, class and caste. They have histories. This article seeks to situate the space of the railway station in Indian history through a look at what it represented in everyday life of colonial India, and how it came to play a crucial role in the Gandhian freedom struggle.

London Illustrated News, 1863.

The summer of 1853 would prove to be transformative for Indian history: the first ever railway travel was undertaken between Bombay and Thana. There is now 100,000 kilometres of railway track throughout the subcontinent. In many ways, railways made possible the territorial integration and further political subjugation of the subcontinent. Historians have argued that it enabled the ‘drain of wealth’, transport of armies and supplies, and in its making transformed ecological niches at a scale hitherto unknown to the subcontinent. In its operations in the incipient spheres of industrial capitalism and communications, “Nothing else in the nineteenth century seemed as vivid and dramatic a sign of modernity as the railroad ”(Prasad 2016)

This dramatic sign of modernity, an imprint of colonial authority, produced dualities in how it was received. In his Hind Swaraj, Gandhi wrote: “railways, lawyers, doctors have impoverished the country so much so that, if we do not wake up in time, we shall be ruined”. Gandhi, Aguiar writes, was not alone in opposing the railways for the benefits it brought to the Raj: spiritual political leaders such as Swami Vivekananda, Aurobindo Ghose, and writer Rabindranath Tagore concurred. For them, railways represented moral corruption and cultural alienation. Amidst these criticisms then, it appears strange that the railway was also the means of transport used extensively by Gandhi and other nationalists, a contradiction highlighted by Prasad. Gandhi unceasingly toured India by rail– the earlier ruinous railways had become the medium of dissemination of the message of satyagraha.

The railways served as the means through which leaders of the nationalist movement

championed the cause of Indian independence. Interestingly, it also became the site through which the popular masses- the same crowds that thronged to catch a glimpse of those leaders at their speeches- articulated their grievances against the colonial Raj. As Prasad argues, this often did not adhere to nationalist leaders’ notions of how independence should be achieved.

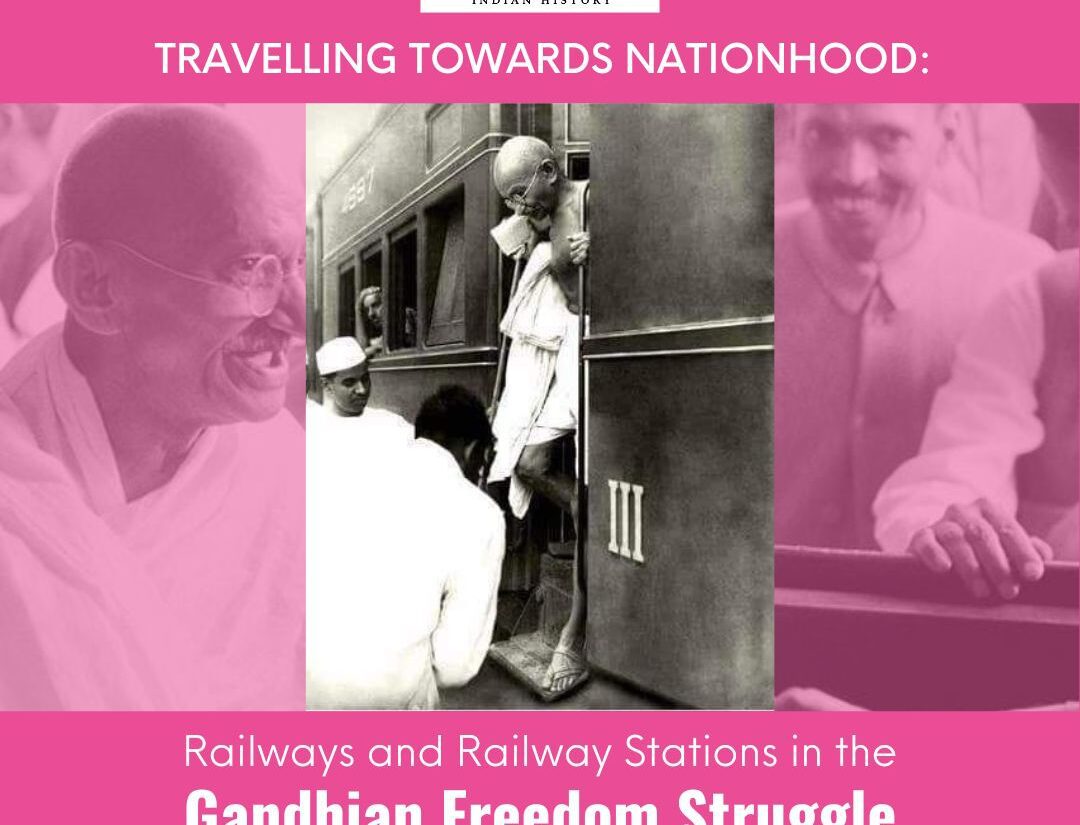

Gandhi looks through a carriage window onto the overspilling crowds seeking to attain his darshan, 1940. Courtesy: Open the Magazine

In the 1920s and 1930s, Gandhi addressed crowds at railway stations, advocating for dismantling colonial rule through satyagraha and achieving swaraj. In his work Gandhi as Mahatma, Amin describes the crowd of peasants assembled at railway stations to attain darshan of the Mahatma. During the Non-Cooperation Movement, this was an exercise in collecting funds for the nationalist movement. Aboard slow trains, Gandhi would alight at every station collecting funds, and spreading his message of satyagraha.

However, railway stations also became a site where the ideas of swaraj and satyagraha, authorised by the Indian National Congress and Gandhi, appropriated, and reworked by the popular masses found expression. This occured in ways that were often unacceptable to the leaders themselves. For instance, Gandhi writes of the annoyance the crowds caused him. In what Prasad calls distinctly ‘un-Mahatma’ like fashion, Gandhi sought to evade the crowds, as he did at the Ahmedabad Railway station while travelling with Vallabhbhai Patel.

The railway station was extensively used for the anti-colonial struggle of the popular masses. Since the 1920s, Ticket-less travel and pulling the alarm chain became a popular means to subvert the Raj. This, despite Gandhi’s insistence that these were not methods that were sanctioned by him. Nonetheless, cries of “Mahatma Gandhi ki Jai” and “Mahatma Gandhi ki jai, ticket nahin hai” became the ritual chant of ticketless voyagers (Chakrabarty 1992; Prasad 2016). In 1925, Ashfaqullah Khan, Chandrashekhar Azad, Thakur Roshan Singh, Rajendra Lahiri and Ram Prasad Bismil robbed a train between Shahjahanpur and Lucknow, staking claim over tax money being transported, whose exorbitant collection had crippled many Indians. This robbery, undoubtedly due to its choice of the attack destination (train) and what it represented (an attack over unjust taxation, the basis of British economic power), was one that “shook the British Raj” (Garg 2022). Attempts of train-wrecking, derailing a train, and a “hartal that spread on railway lines”, too were recorded during this time (Prasad 2016).These displays of nationalism, contrary to the authorised by leaders, speak to the nature of the freedom struggle: notions of swaraj, and how to achieve it were not a monolith.

Later, during the Quit India Movement (1942-1945), railway stations again became the site of popular resistance. In the United Provinces alone, 104 railway stations were seriously damaged or destroyed. Considering this, it comes as no surprise that the British aggressively sought to reassert their authority through the railways. Ticketless travel became a non-bailable offence, and English troops were stationed at railway stations, For instance, the mob at the Kasur Railway station was dispersed through firing.

To understand why the railways became the site where colonialism itself was challenged and reinforced, it is necessary to understand how the institution came to stand in for colonialism and what it meant to the ordinary Indian. In 1919-1920, 520 million passengers undertook a journey by rail at a time when the Indian population stood at 318 million. This shows the extent of the railway’s reach in the subcontinent. The Indian encounter with the railways was however, marred by experiences of racial subjugation. Indian passengers’ treatment aboard was deplorable: forced to travel in the third class compartments, their carriages had no access to drinking water and they could not deboard at intermediate stoppages. Women passengers in particular were subjected to violence. Amongst the Indians, upper caste elites, forced to travel into third class compartments enacted violence upon “untouchable” passengers– the carriage was a microcosm for the nation.

The railways had inextricable ties to famine: Marian Aguiar writes how it was not just that the railways could not overcome the famine, but that through the redirected shipment of grains and resources, it had actively contributed to it. The architecture of stations (primarily Victorian), and the exclusively white higher-level employees of the Railways betray its racially charged nature.

Gaganendranath Tagore, Trains and Women, 1916, courtesy Ian J. Kerr (2003).

These features of the railways had the unintended, unforeseen consequences of fostering solidarities. Gandhi, citing the reason he chose to travel in the third class compartment when he could have been a first-class passenger said: “Had I never travelled 3rd class, I would never have felt like the poor and been one of them”. This feeling of “being one” of a larger group, arguably a prerequisite for any mass movement was thus engendered through the shared experience of the railways.

In these ways then, journeying by rail in twentieth century India did not just entail physical travel. It was a journey between past and present (a break from tradition into modernity; both changes and continuities in the ways social hierarchies were manifested), and through their role in dismantling British rule, tunnelling toward the future. Railways form a powerful mirror for society– everyday travel in the bogeys took the form of overarching hierarchies of colonial society. Railways represented mobility– a symbolic and corporeal form of both power and resistance to it. Railway stations serve as places of congregation, of tangible symbols of power of governing authorities. It is thus no wonder that both railway stations and trains continue to signify the success of the governing authorities. Railway stations do not merely mark the arrivals and departures of trains– but of regimes, of collective consciousnesses and responses to regimes.

Bibliography

Chakrabarty, Bidyut. “Defiance and Confrontation: The 1942 Quit India Movement in Midnapur.” Social Scientist (1992): 75-93.

Prasad, Ritika. Tracks of Change: Railways and everyday life in colonial India. Cambridge University Press, 2016.

Aguiar, M., 2011. Tracking Modernity: India’s Railway and the Culture of Mobility. U of Minnesota Press.

Kerr, Ian J. “Representation and representations of the railways of colonial and post-colonial South Asia.” Modern Asian Studies 37, no. 2 (2003): 287-326.

Chatterjee, Arup K.. The Great Indian Railways: A Cultural Biography. India: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019.

Garg, Prachi. Kakori. India: Srishti Publishers & Distributors, 2022.

Bear, Laura. Lines of the Nation: Indian Railway Workers, Bureaucracy, and the Intimate Historical Self. United Kingdom: Columbia University Press, 2007.