Urdu

Cultural history of Urdu can be traced back to the confluence of Persian, Arabic, and local dialects in India, evolving into a rich literary medium during the Mughal era. In understanding Urdu’s development, scholars agree that the language is a product of the creative interaction between West Asian and classical Islamic linguistic traditions and local Indic languages. This fusion led to the creation of a literary language that, by the early 18th century, began to overshadow Persian in importance at Delhi. While retaining its Indic grammatical and lexical base, Urdu steadily incorporated Persian genres and imagery. Major centers of Urdu literature and scholarship eventually emerged in cities such as Lucknow, Lahore, Hyderabad, and Delhi.

Birth of Poetic Patriotism

Urdu patriotism during the freedom struggle was especially witnessed during the closing years of the nineteenth century and the early twentieth century with the emergence of two prominent patriotic poets: Durga Sahay Suroor Jahanabadi and Mohammad Iqbal. Iqbal’s notable works included “Himala,” “Aftab” (a translation of the Gayatri Mantra from the Vedas), and the iconic “Taranah-e-Hindi,” which remains one of the most beloved national songs in India. Even today, it resonates with Indian children, encapsulating Impact of Urdu poetry on national movement –

“Sāre jahān se achhā, Hindostān hamārā,

Ham bulbulein hain is kī, yeh gulsitān hamārā…”

(India, our homeland, is the best in the world,

This is our garden, and we are its nightingales…)

( Mohammad Iqbal )

This modern sense of patriotism in Urdu poetry had begun to take root during the decline of the Mughal Empire as British imperial ambitions became increasingly evident. Indian intellectuals started to recognize that reclaiming their territorial and political independence might demand the ultimate sacrifice. This realization prompted Urdu poetry to gradually embrace patriotic themes more explicitly. Iqbal, in particular, issued a passionate warning against the perils of British imperialism with verses like:

“Na samjho ge to mit jaoge ae Hindustan walon,

Tumhari dastan tak bhi na hogi dastano mein.”

(O Indians, if you do not awaken, you will be destroyed,

And your story will not even be remembered in history.)

This verse aptly highlighted the dire consequences of complacency in the face of injustice and repression by the British. Alongside this, the concept of ‘Inqilab’ – revolution, became a central theme in Urdu poetry, embodying the spirit of resistance and galvanizing the masses to rise against British rule.

Poems of Resistance and Revolution

As the First World War unfolded, Urdu resistance poetry coupled with nationalist sentiments found new expression through the works of poets like Chakbast and Hasrat Mohani. Chakbast, known for his moderate views, drew inspiration from leaders such as Bipin Chandra Pal, Gokhale, and Annie Besant. His poems—‘Khak-e-Hind’, ‘Awaza-e-Qaum’, and ‘Hamara Watan Dil se Pyara Watan’—reflected the liberal-moderate aspect of the freedom movement.

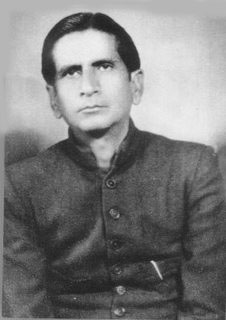

(Brij Narain Chakbast)

In contrast, Hasrat Mohani, an ardent extremist, refused to settle for anything less than full independence thus was unwavering in his demand for ‘swaraj’—complete self-rule for India.

(Hasrat Mohani)

This period not only saw a remarkable display of Hindu-Muslim unity but also an intensifying anti-colonial fervor through the The Khilafat Movement, which marked the first major mass struggle against colonial rule, playing a crucial role in the evolution of Urdu literature and patriotism. Among these voices of this period, Muhammad Ali Jauhar stood out as a distinguished figure choosing the pen over the sword. H.G. Wells once remarked about Jauhar: “Muhammad Ali possessed the pen of Macaulay, the tongue of Burke, and the heart of Napoleon”. Jauhar in one of his stirring verses, writes:

“ daur-e-hayāt aa.egā qātil qazā ke ba.ad

hai ibtidā hamārī tirī intihā ke ba.ad ”

(Life will begin anew when the tyrant has been vanquished,

Our beginning will come after you have reached your end.)

These lines capture the essence of his belief that true life and freedom would flourish only after the oppressor’s downfall.

Another of the most eminent Urdu poets in the struggle for freedom, known for his romanticism was Josh Malihabadi. Due to his unrelenting efforts in the struggle for freedom, Josh Malihabadi earned the title of “Shaayar-e-Inquilab” – the Poet of Revolution. His pen ignited enthusiasm in the hearts of those who championed ideals of equality, religious liberty, and fraternity –

“kaam hai merā taġhayyur naam hai merā shabāb

merā na.ara inqilāb o inqilāb o inqilāb”

(My task is change, my name is youth!

My slogan: revolution and revolution and revolution!)

(Josh Malihabadi)

Thus, the period around the First World War marked a transformative phase in Urdu poetry, where the voices of resistance and revolution intertwined with the broader currents of the nation’s freedom struggle, leaving a lasting legacy on Urdu poets and Indian independence.

The Progressive Writer’s Movement

“The Anjuman Tarraqi Pasand Mussanafin-e-Hind”, known as the Progressive Writers’ Movement, was a groundbreaking literary initiative in pre-partition British India. Emerging in the 1930s, the movement was distinctly anti-imperialistic and left-oriented. From the very beginning of British rule in India, Urdu literature had maintained an anti-British and pan-Indian stance. However, in its early stages, this resistance was largely passive. As Ahsan Faruqi notes , the progressives shifted the focus of literary experience from abstract universals (afaq) to the concrete realities of people and their lives (anfus), emphasizing the lived experiences of the oppressed, enriching the trajectory of Urdu poetry and revolutionary movements.

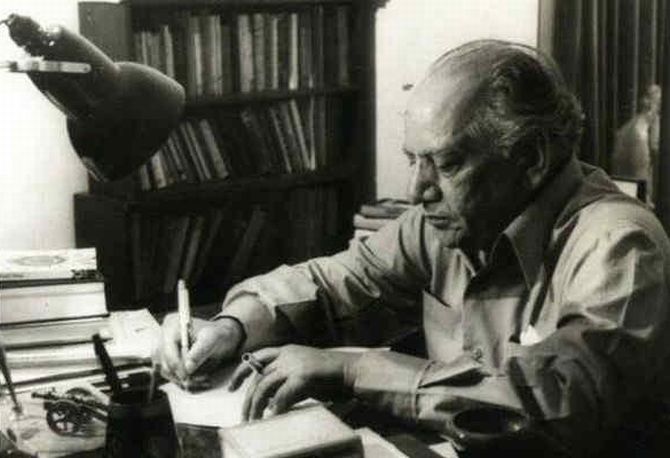

Gopi Chand Narang, writing about the progressive poets, observes that they believed in the possibility of bridging the gap between rich and poor. The impact of Urdu poetry on the national movement was such that it envisioned a free country where science and technology would help generate wealth and build a society offering equal opportunities for all. Among the prominent poets of this movement were Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Ali Sardar Jafri, and Asrarul Haq Majaz. Arguably the most renowned Urdu poet, Faiz Ahmad Faiz’s works combined doctrinal correctness with traditional imagery fueling a sense of righteous indignation against the oppression of the poor.

(Faiz Ahmed Faiz)

Majaz, like Faiz, infused his poetry with active rebellion. His verses often intertwine themes of nature with revolutionary ideals, equating anti-British nationalism with the broader struggle for revolution.

(Asrarul Haq Majaz)

An important dimension in the earlier literary movements was their appraisal of women as sources of pride yet failing to address their rights. The Progressive Writers’ Movement, however, tackled this issue head-on. As early as 1937, Majaz delivered a powerful message to the women of India:

“tire māthe pe ye āñchal bahut hī ḳhuub hai lekin

tū is āñchal se ik parcham banā letī to achchhā thā”

(The scarf on your forehead is beautiful indeed,

But it would be better still if you turned it into a flag.)

This call to transform traditional symbols of modesty into emblems of resistance highlighted the movement’s commitment to gender equality and empowerment. The Progressive Writers’ Movement contributing to the broader struggle for social justice and freedom in India enhanced the role of Urdu poetry in resistance movements.

Partition and Post-Independence Landscape

The decade leading up to Partition was a time of upheaval in colonial India. The two world wars had caused substantial physical and social dislocation parallel to this, the dream of Hindu-Muslim unity was crumbling, with Muslims increasingly advocating for some form of autonomy, while the Congress Party insisted on a strong, centralized state. Despite the ideological pressures exerted by the two new nation-states, poets—such as Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Sardar Jafri, Majaz, and others—refused to be confined by narrow nationalistic controversies and contributed empathetically to Urdu literature and patriotism. One poem stands out as a powerful memorial to the tragedy of Partition: Faiz Ahmad Faiz’s “Subh-e-Azadi” (“Dawn of Independence”) –

“Ye daaġh daaġh ujālā ye shab-gazīda sahar,

Vo intizār thā jis kā ye vo sahar to nahīñ,

Ye vo sahar to nahīñ jis kī aarzū le kar,

Chale the yaar ki mil jā.egī kahīñ na kahīñ.”

(This is not that Dawn for which, ravished with freedom,

We had set out in sheer longing,

So sure that somewhere in its desert the sky harbored

A final haven for the stars, and we would find it.)

Through “Subh-e-Azadi,” Faiz eloquently conveys the bitter realization that the dawn of independence was not the bright, hopeful new beginning many envisioned. Instead, it was a day marred by the bloodshed and disillusionment of Partition, a failed dream amidst the wreckage of a violent history.

Conclusion

The Role of Urdu literature in the freedom struggle was undoubtedly extensive, serving as the unifying language of revolution and resistance. The widespread use of Urdu, more prevalent than English, enabled the sharing of ideas across the diverse regions of India.

Gopi Chand Narang notes that Urdu’s power as a language of revolt was amplified by the contributions of poets like Ram Prasad Bismil, whose verses, “Sarfaroshi ki tamanna,” captured the spirit of sacrifice. The slogan “Inquilab Zindabad,” coined by Hasrat Mohani, became synonymous with the freedom movement. The impact of Urdu poetry on the national movement extended beyond its own script, with Hindi poets publishing their work in Urdu newspapers due to limited Hindi publications. Echoing the patriotic Zeitgeist, Urdu poets in the struggle for freedom not only expressed the collective yearning for freedom but also created an emotional climate in which millions rose against colonialism, ultimately leading their country to the dawn of independence.

References –

Narang, Gopi Chand. “Thoughts on August 15th: The Indian Freedom Struggle and Urdu Poetry.” Indian Literature 29.4 (114 (1986): 127-139.

Minault, Gail. “Urdu Political Poetry during the Khilafat Movement.” Modern Asian Studies 8.4 (1974): 459-471.

Zaib, Aurang, Muhammad Yasir, and Mohammad Usman. “The Role of Urdu Literature in the Independence Struggle of the Subcontinent.” Pakistan Languages and Humanities Review 7.1 (2023): 421-433.

Yahya, M. D. “Traditions of Patriotism in Urdu Poetry: A Critical Study with Special Reference to the Poet of the East Allama Iqbal and His Poetry.” Journal of Contemporary Research 1.2 (2013).

Qureshi, Omar. “Twentieth-century Urdu literature.” Handbook of Twentieth century literatures of India (1996): 329-362.

Wani, G.H. Hassan. “Nationalism in Urdu Poetry: A Special Study of Some Urdu Poems.” Erothanatos, vol. 2, no. 2, Apr. 2018.

https://www.dawn.com/news/1154854

- Cultural history of Urdu poetry

- Freedom struggle and Urdu poets

- Impact of Urdu poetry on national movement

- National movement through Urdu literature

- Role of Urdu literature in freedom struggle

- Urdu language in Indian independence movement

- Urdu literature and patriotism

- Urdu patriotism during freedom struggle

- Urdu poetry and revolutionary movement

- Urdu poetry cultural history

- Urdu poetry in national movement

- Urdu poetry in resistance movements

- Urdu poets and Indian independence

- Urdu poets in the struggle for freedom

- Urdu resistance poetry