By Vaibhavi Danwar

The Indian summer as hot, long, and relentless was not only a season under British colonial rule, but it also became a metaphor for the empire’s view of India itself. Colonial officials, doctors, and travel writers often described the heat of the summer as stifling and deadly, reinforcing notions of tropical degeneracy and the assumed superiority of temperate European climates. This climatic script was inextricably tied to the imperatives of imperial domination: unbearable summer represented an empty space awaiting rule, order, and regeneration. In addition, contemporary time demonstrates that khadi remains very appealing to young Indians, as much patriotic memory as an eco-friendly and climate-friendly option.

Colonial Heat and Climatic Orientalism

In British colonial rhetoric, the Indian summer was not only a climatic event, it was an ideological construct. The searing heat of the subcontinent began to embody not only environmental excess but also a wider cultural and racial story of excess, stagnation, and disorder. For colonial officials and authors, India’s hot summer was a symbol of an ungovernable country, one whose climate mirrored, and allegedly exacerbated, its moral and social disarray. The sun-baked, dusty summer was set in contrast to Britain’s temperate climates, an unstated inference that just as India’s climate was excessive and uncontrolled, so were its people and institutions.

Climatic orientalism scholarship has highlighted how European empires employed environmental conditions to build hierarchical binaries, civilized and barbaric, temperate and torrid, rational and emotional. As Rajagopal explains in Exploring Gandhian Science, the colonial medical establishment often associated the Indian heat with disease, exhaustion, and irrationality, both physical and moral (Rajagopal, 2009, pp. 68–70). The summer then became an imperial trope of necessity: only the “cool logic” of British rule, it was said, could impose order upon such a hot land. Colonial officers’ and memsahibs’ memoirs typically described the Indian summer as something to flee, retreating to hill stations, covering themselves in multiple layers of European clothing, or imprisoning themselves indoors to endure what was seen as an unlivable season. But this colonial unease at the Indian summer was not just physiological, it was epistemological. The weather was interpreted through a framework that aimed to invalidate native ways of living, clothing, and behavior. Handloomed clothes, particularly those appropriate for the heat, were deemed primitive or unhygienic. This erasure of indigenous climate adaptation knowledge, including breathable cottons and light, airy buildings, furthered the imperial interest in representing Indian society as behind and requiring intervention by the West.

Fashioning Comfort in the Colonial Heat

Colonial medical discourses and administrative documents often stressed the necessity of “civilized” infrastructure, “proper” attire, and “rational” housing to survive India’s rigorous climate standards implicitly based on European sensibilities. In contrast to this, khadi appeared not only as a political icon, but as an embodied, climatologically aware alternative based on local knowledge and experience.

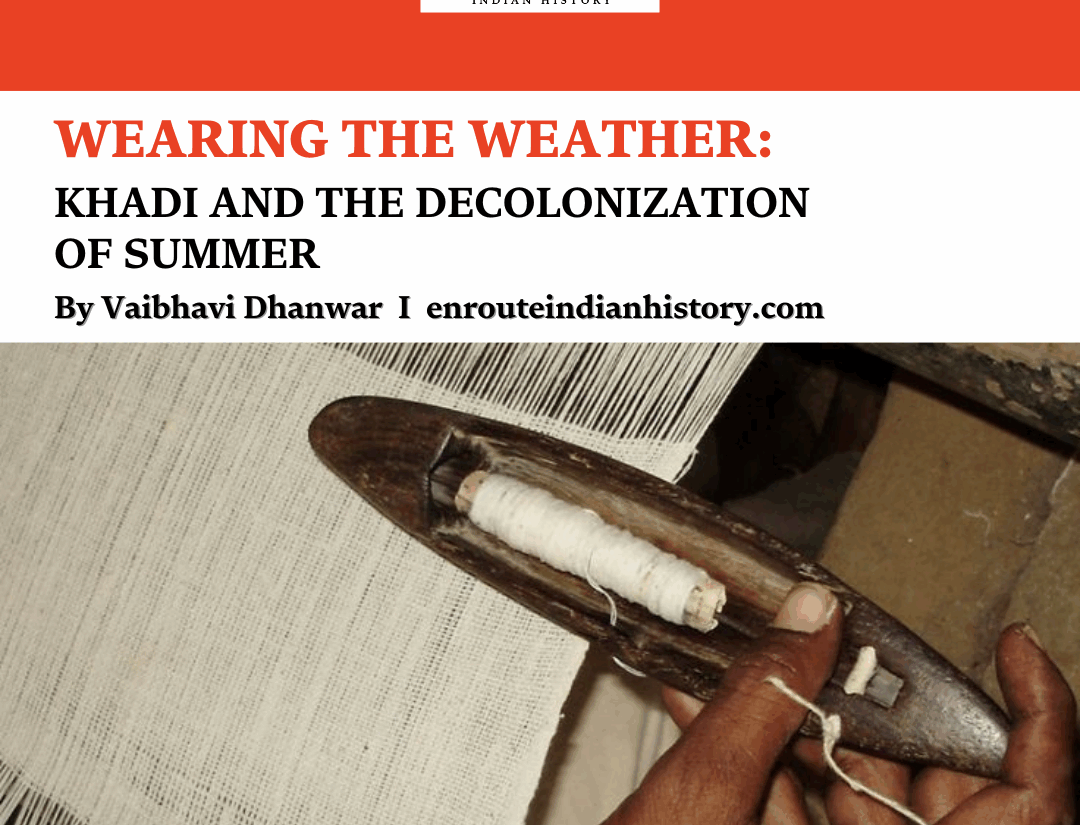

Gandhi’s call for khadi was not symbolic, it was a utilitarian repudiation of the colonial industrial model of production, consumption, and dressing too. (Rajagopal, 2001) As a handspun cotton cloth, khadi was best adapted to India’s weather conditions. Light, porous, and airy, it made the body cool and let the air pass through in hot summer temperatures. As opposed to the heavy European cloth imported via colonial commerce, which was unsuitable for India’s climate, khadi represented a cloth that worked with the weather instead of fighting it.

Gandhi frequently described khadi in natural, corporeal language: it “breathed”, it “served”, it “freed”. It is not accidental vocabulary: it stresses the way in which khadi was part of an aesthetic ecology where clothing was not merely political or cultural, but profoundly ecological. In avoiding colonial dress (which symbolized status and conformity) and embracing khadi, Indians were not merely identifying themselves with swaraj (self-governance), but appropriating a relation to the climate that was adaptive, intimate, and humane. Parul Gill et al., in their paper Khadi: A Proud Choice of Indian Youth, support this argument through their research on the current attitudes towards khadi. To this day, the cloth is admired not merely for its patriotic connotation but also for its climatic usefulness. Amongst youth respondents, one of the key draws towards khadi clothing was its ease of wear during summer, particularly in rural and semi-urban India. This continuity shows that khadi’s relationship with the Indian summer is not a relic of history, but an ongoing cultural and material adaptation to climatic reality.

Sartorial Resistance of khadi

Gandhi’s invocation of khadi was deeply performative and symbolic (R. Rajagopal, 2001) The khadi movement was not merely a political protest against industrial capitalism and colonial economic control, it was a scientific, aesthetic, and ethical reimagining of Indian selfhood. By advocating for a hand-woven cloth appropriate to India’s hot and humid summers, Gandhi rallied the Indian body itself as a site of resistance: to wear khadi was to express climatic accommodation over colonial unease, self-reliance over dependence, and dignity over dispossession.

Compared to British insistence on stiff, woolen uniforms and “civilized” dress codes inappropriate for Indian weather, khadi addressed a decolonization of fashion. Khadi enabled the Indian subject not just to survive but to flourish in summer heat, making the season itself from an emblem of disorder to a canvas of national rebirth. The selection of fabric became indivisible from identity politics. Modern scholarship substantiates this link. As Parul Gill et al. put it, khadi these days still calls up an “emotional connect with India’s freedom” and is being progressively taken up by the younger population for its sustainable, breathable, and culturally related characteristics. It demonstrates how the material, set in a time of colonial history, has reached beyond that phase to communicate even now.

The British colonial project framed the Indian summer as a symbol of disorder unhygienic, feverish, and fatal. In contrast, khadi emerged as a quiet but powerful rebuttal to this narrative. Its practicality in extreme heat, coupled with its association with self-sufficiency, redefined not only the politics of clothing but also the very experience of enduring summer in India. This paper has shown that khadi transcends its role as mere fabric. It becomes a material metaphor for reclamation—of season, of climate, of body, and of nationhood. By embracing breathable, local, and sustainable cloth, Indians did not just resist colonial goods—they reclaimed the summer itself, asserting it not as a site of colonial pathology, but as a space of lived adaptability, dignity, and creativity.

References

(Rajagopal, R., 2001.) Exploring Gandhian science: A case study of the Khadi movement. ResearchGate. Pp.68–111.

(Gill, P., Malik, P., Arya, N. and Yadav, N., 2023.) Khadi: A proud choice of Indian youth. International Journal of Home Science

- August 28, 2023

- 6 Min Read