Love is eternal, transcending time and space. It is an emotion conveyed through gestures, gifts, poetry, art, monuments, and so much more. This article explores the theme of love through archaeological finds that quintessentially represent Indian romance in all its glory. Equally still, reverence, admiration, and yearning are all emotions that embody love in Indian history.

Stones, Bones and Being Human

Love and care are intrinsic to humans. Prehistorically, we see it manifest through artifacts, ancient funerary practices, and paintings, to name a few. What is now perhaps the oldest evidence of care for a living being, and as an extension, love for kin, is the toothless skull (cranium and mandible) of an old individual of Genus Homo from Dmanisi, Georgia. This fossil proves that he lived many years, even though he had lost almost all his teeth, with the help of others who would either process or procure his food. According to Kohn and Mithen (1999), even stone tools, especially the handaxe, are considered symbols of love. Although a controversial hypothesis (Nowell and Chang, 2009), the basis of the argument is the symmetry of handaxes or their over-emphasized design. Nevertheless, it is a fascinating take on the first tools of humanity, a symbol of the ideal mate.

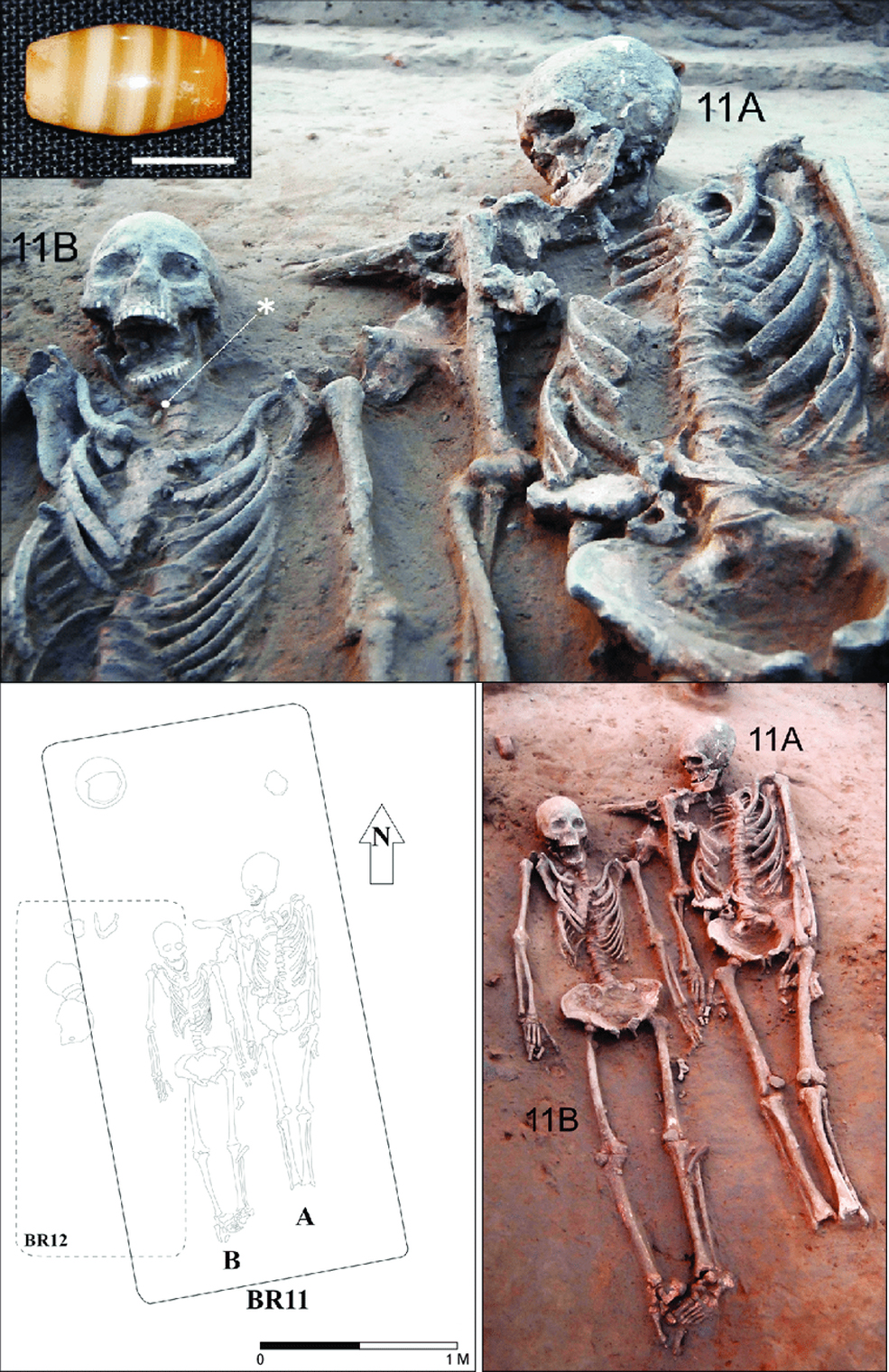

An interpretation of love, with the help of Indian Archaeology, would be the famous joint burials or couple burials of the Harappan Civilisation. Excavations at the site of Lothal, Gujarat, revealed the first joint burials of the Harappan Civilisation, one lined with bricks. However, their status as a couple is controversial. The first credible evidence of a burial of a couple of this period comes from the site of Rakhigarhi, Haryana. According to Shinde et al. (2018), the couple, a pair of young adults, were buried around the same time or together. The male skull is turned towards the female, almost as if he were looking at her, even in the afterlife. Another significant group of archaeological artefacts indicating love would be the grave goods interred with the body. If we keep the concept of the afterlife aside, grave goods like jewellery, toys, and tools could denote love and care.

Top: 11A (male) facing 11B (female); Bottom: Overview of the couple’s burial.

Source: Shinde et al. 2018. A young couple’s grave was found in the Rakhigarhi cemetery of the Harappan Civilization. Anatomy & Cell Biology

Writing and Painting Love

Jogimara cave inscription

Source: https://puratattva.in/sitabenga-jogimara-caves-colors-of-drama/

Fast forward to the 3rd century BCE to Jogimara Cave, Chattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh. Here is an inscription in the Magadhan Prakrit language and what could be the oldest recorded letter of admiration in India. Scholars, however, stand divided by its translations and what it could denote. Another medium depicting love is the paintings, especially those from the Ajanta caves. Dating as far back as the 2nd century BCE, these caves have preserved some of the best cave paintings in the world. The main themes painted are the life of Buddha and the Jataka tales. Speaking of love, the story of Udayin and Gupta from Cave 17 depicts it elegantly. Udayin, having decided to devote his life to Buddha and become a monk, is seen placating a disappointed Gupta. A painting depicting the story of Simhala, lured by a Rakshasa, is also observed. Additionally, Cave 17 has paintings of Mithuna couples and other ordinary couples.

Left: The story of Udayin and Gupta, Cave 17; Right: Couples on the door lintel, Cave 17.

Source: Sailko 2019 Wikimedia commons; https://www.trawell.in/maharashtra/ajanta-caves/cave-17-18

Around a similar timeframe, poet Kalidasa wrote about love in different forms through poems like Meghadoot and broader works like Malavikagnimitram, Vikramorvasiyam and Abhijanasakuntalam. Adhikari and Saha (2021) note that Raja Ravi Varma contributed towards reviving the works of Kalidasa, especially Abhijanasakuntalam with his depiction of Shakuntala.

Love and the Divine

Kamadeva and Rati at Khajuraho

Source: Basu, A. 2016. Rati & Kamadeva, Khajuraho.

https://www.worldhistory.org/image/5448/rati–kamadeva-khajuraho/

In Indian history, Kamadeva is the God of Love. Perhaps he is the predecessor and Hindu counterpart of Cupid. He is also known as the God of Joy (madana) and Desire. Similarly, his wife (or consort) Rati is also known as the Goddess of Desire. According to the Puranas, Kamadeva was burned to death by Shiva’s third eye for being interrupted during his deep meditation. This tragedy and necessary sacrifice are acknowledged and celebrated as Holi all over India. This festival, also known as Madana Mahotsav, celebrates joy and love in spring. In Tamil Nadu, Holi goes by other names like Kaman Pandigai or Kama-Dahanam. Sculptures of Kamadeva and Rati are present in Khajuraho Temple, Madhya Pradesh; Soundararajaperumal Temple, Tamil Nadu; Chennakeshava Temple, Karnataka; and Madan Kamdev, Assam, to name a few. At Soundararajaperumal Temple, there is a separate shrine for Kamadev and Rati for separated couples seeking to reunite.

Raja Ravi Varma 1898, Shakuntala Removing a Thorn from Her Foot

https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/shakuntala-removing-a-thorn-from-her-foot-raja-ravi-varma/UgFGr-9kgW8y7g

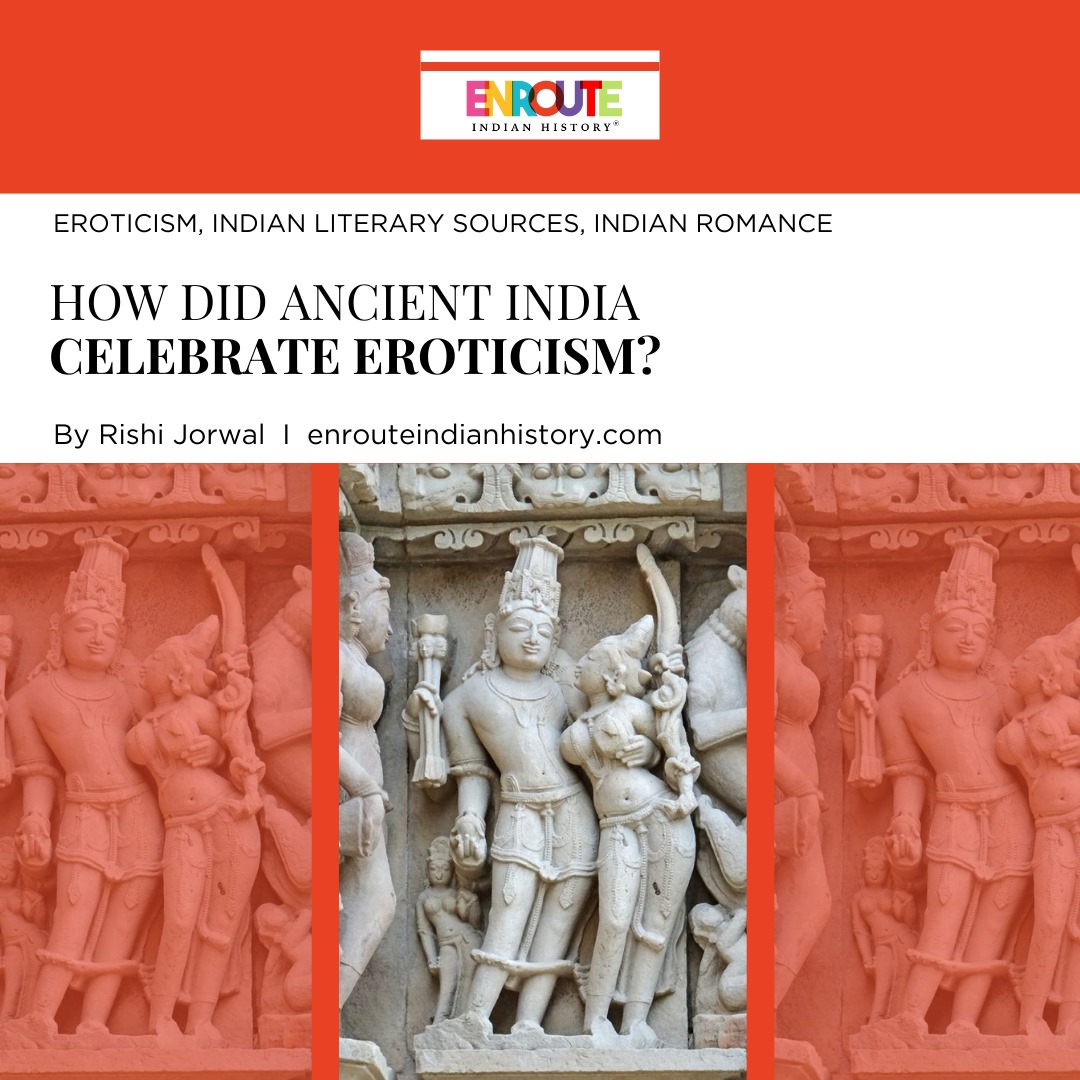

The Kamasutra by Vatsyayana of possibly the 3rd century CE is a Sanskrit literary text and guidebook on love and sex. According to Doniger (2003), “It is a book about the art of living – about finding a partner, maintaining power in a marriage, committing adultery, living as or with a courtesan, using drugs – and also about the positions in sexual intercourse”. Many aspects of the Kamasutra have been immortalised on the walls of temples like the Khajuraho, Madhya Pradesh, Modhera Sun Temple, Gujarat, Virupaksha Temple, Karnataka, to name a few. The most prominent among these temples is the Khajuraho group of monuments built under the patronage of the Chandela dynasty of the 9th century. Khajuraho represents religious tolerance, portraying Vaishnavism, Saivism, and Jainism, but is widely known for its representation of kama. The Khajuraho group of monuments is almost like an anomaly in the current representation of Hinduism. There is a constant tussle between these being a beautiful representation and celebration of erotica and sex, all innate human tendencies, while also being ridiculed and criticised by conservatives. Vijayakumar (2018) aptly talks about this “dichotomy of being damned as pornography and the transgression of Indian culture on the one hand, and on the other being endorsed… as an epitome of Indian liberalness – as the quintessential Kamasutra Temple”.

Khajuraho Group of Temples, Madhya Pradesh

https://www.andbeyond.com/advice/asia/india/why-visit-khajuraho/

https://www.tripadvisor.in/AttractionProductReview-g297647-d13123083-UNESCO_s_Western_Temples_at_Khajuraho_A_Walking_Tour-Khajuraho_Chhatarpur_District.html

Although celibacy features prominently in Jainism, the 11th-century Bhairava Padmāvatī Kalpa, a Jain tantric text by Mallisena, stands apart. It is dedicated to Goddess Padmavati and describes the ways of her worship. Additionally, it prescribes “rituals related to erotic love and forceful attraction which objectifies women as desired objects” (Jain, 2019). A century later, we have Geeta Govinda by Jayadev, which explores a different aspect of love in the form of devotion. It describes the love between Krishna and Radha.

Poetry of Love

The Mughal Period is replete with symbolism of love. One of the most beautiful and well-known symbols of love, encased in marble, is the iconic Taj Mahal. Constructed in the 17th century, perhaps nothing says ‘I Love You’ better than this pearlescent beauty. Zahiru’d-din Muhammad Babur wrote many poems about his love for his homeland. He also questioned his sudden infatuation with a boy named Baburi. “In those leisurely days I discovered in myself a strange inclination, nay!… ‘I maddened and afflicted myself’ for a boy in the camp-bazaar, his very name, Baburi, fitting in.” (Beveridge 1922, p. 120). The last Mughal Emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar, was well known for his poetry and command over the Urdu language. In his final years and during his exile in Rangoon, he wrote about his yearning for Delhi. “Kitna hai bad-nasib ‘Zafar’ dafn ke liye Do gaz zameen bhi na mili ku-e-yaar mein” “How unfortunate is ‘Zafar’ who is unable to find for his burial even two yards of ground in the streets of his beloved”.

These are just a few expressions of love unearthed and found through Indian archaeology from an unfathomable ocean of Indian romance. Even though countless artifacts have succumbed to time, many more are yet to be discovered. Some have immortalized their emotions in stone, while some agonised to have ever felt it. The pain, anguish, and lament, or the joy, comfort, and security that love provides, is a virtue cherished by humanity. It has paved the way for artistic freedom and will continue to inspire creative expression for future generations.

References:

Adhikari, A. and Saha, B. 2021. Shakuntala: As Authored by Kalidas and Painted by Raja Ravi Varma. Galore International Journal of Applied Sciences and Humanities 5(4):45-53 DOI:10.52403/gijash.20211008

Archaeological Survey of India. Annual Report 1903-04. p. 128. Calcutta: Office of The Superintendent of Government Printing, India.

Beveridge, A.S. 1922. The Babur-Nama in English (Memoirs of Babur). Translated from the original Turki text of Zahiru’d-din Muhammad Babur Padshah Ghazi. Vol. I London: Luzac & Co.

Doniger, W. (2003). The “Kamasutra”: It Isn’t All about Sex. The Kenyon Review, 25(1), 18-37. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4338414

Jain, V. (2019). Erotic Desires and Coercive Love in Jain Tantra: Textual Reading of Bhairava Padmāvatī Kalpa. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, 80, 254-260. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27192879

Kohn, M. and Mithen, S. 1999. Handaxes: products of sexual selection? Antiquity 73(281):518-526. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00065078

Nowell, A. and Chang, M.L. 2009. The case against sexual selection as an explanation of handaxe morphology. Paleoanthropology pp. 77-88.

Tripathi, S. and Jain, B. 2019. Portrayal of Woman in the Cave Paintings of Ajanta. International

Journal of Research-Granthaalayah Vol. 7.

Vijayakumar, S. 2018. The Sacred and the Sensual: Experiencing Eroticain Temples of Khajuraho. Via Tourism Review Vol. 11. DOI 10.4000/viatourism.1792 https://journals.openedition.org/viatourism/1792

https://en.rattibha.com/thread/1625402083469066241

https://theeducationist.info/love-poems-ancient-and-medieval-india/

https://cavesofindia.org/udayin/

https://arttreasuresindia.blogspot.com/2015/11/scene-from-simhala-avadana-jataka-story.html

https://www.pickpackgo.in/2017/05/a-guide-for-ajanta-caves-part-6.html

https://www.sahapedia.org/away-home-how-babur-versified-his-pain-exile-and-homelessness#_edn4

https://www.prathaculturalschool.com/post/bahadur-shah-zafar-poetry

- February 19, 2024

- 6 Min Read

- February 16, 2024

- 9 Min Read

- February 16, 2024

- 8 Min Read