At Rashtrapati Bhavan, you may find the Rampurva Bull, a magnificent sandstone capital of the Ashokan Pillar, on the balcony in front of the main entrance of Durbar Hall. The bull, which dates back to the third century BCE, connects the modern Indian capital to the Classical Era in ancient India when the Mauryan power was the first subcontinental power.

(Rampurva Bull Capital at Rastrapati Bhavan; image by Soham Dutta, March 2022)

The connection between the empire and its king, Ashoka, went beyond a superficial level; it had profound origins in Delhi. The city is closely associated with the Ashokan edicts, some of which were found in their original location (the Minor Rock Edict), while others were reused or moved by later medieval and colonial rulers (the Major Pillar),[Edicts]. So, intentionally or unintentionally, individuals from different periods engaged with Ashokan’s legacy.

Hence The Piyadasin spoke: Minor Rock Edict of Bahapur

( Rocky outcrops around MRE; image by Soham Dutta, March 2023)

First brought to notice by Mr.Jung Bahadur on an outcrop of Arravalis in South Delhi in the village of Bahapur near Kaklaji temple, archaeologists B.M. Pandey and M.C. Joshi identified this inscription as the Minor Rock Edict of Ashoka on June 23, 1966. This inscription is primarily important for being part of a series called MRE 1, which was the first attempt to communicate with his subjects through an epigraphic communique. The location of the inscription, which is near the Kalkaji and lies in a north-south orientation between the Mathura-Purana Qila alignments, is also notable. According to Dilip Chakarbarty(2011), its location on the southern parts of Delhi Ridge near Kalkaji temple, which was also important for its pre-historic artifacts ranging from paleolithic to microlithic, and the current-day importance of the worship of Kalkaji should be noted. Whether the antiquity of the sacredness of the spot reaches to pre-historic or early historic periods is uncertain, but it can certainly be said that, as opined by D.C. Sircar, it was meant for the dwellers of Indraprastha, which was a prosperous urban center by the age of Maurya. Based on its contents, which are as follows (Translated by B.M. Pandey and M.C. Joshi):

“Devānampiya (His Majesty) saith (thus). It has been more than two and a half years that I became a lay devotee, (but) I did not exert myself greatly (in the cause of Dhamma). It was more than a year after my joining the samgha, and I exerted myself greatly. (Consequently) I could unite with the gods; the mortals (who had so far been) ununified with gods during this period in Jambudvīpa (India). (This is the outcome of exertion. (And) it is not to be accomplished only by the men of importance, (but) even lowly-placed ones if they exert can attain heaven. For this purpose, this proclamation (is being made) (so that) both the low and the high (poor and rich) may exert (in the cause of Dhamma) and (those living on and beyond the borders of my kingdom) may also know about this.

Let this exertion be ever-enduring, and this objective will also be immensely increasing (certainly) to the extent of one-and-a-half fold.”

(Figure 1: Minor Rock Edict of Bahapur, Figure 2: A closer look of MRE; image by Soham Dutta, March 2023)

Patrick Olivelle (2023) notes that “for the first time, Ashoka explicitly refers to his not just becoming Buddhist but a Buddhist lay devotee… called an Upasaka. It is noteworthy that the term ‘dharma’ does not occur in this edict”. According to Lahiri, “The message is partly confessional, presenting his self-realization and organizing it in terms of a chronological pattern of development.”. Lahiri goes on to say that the emperor’s hesitation to expound a powerful doctrine immediately after the king’s conversion may have been deemed desirable, as the graduated process would have been far more effective in ensuring future zeal. John Strong (2012) adds another dimension by stating that “implicit in the first edict was the idea of a ‘double utopia’ in which gods and humans mingled either on earth or later in heaven,” which he believes was the beginning of a new moral world. According to Lahiri, these universes promote a socially inclusive view in which both the lowly and the exalted can exist on the same moral plane and achieve heaven (svarga). Thus, even though it was not explicitly stated, this series of edicts served as the beginning of the Ashokan project of ‘Dhamma’.

( A newly built gazebo by Archaeological Survey of India; image by Soham Dutta, March 2023)

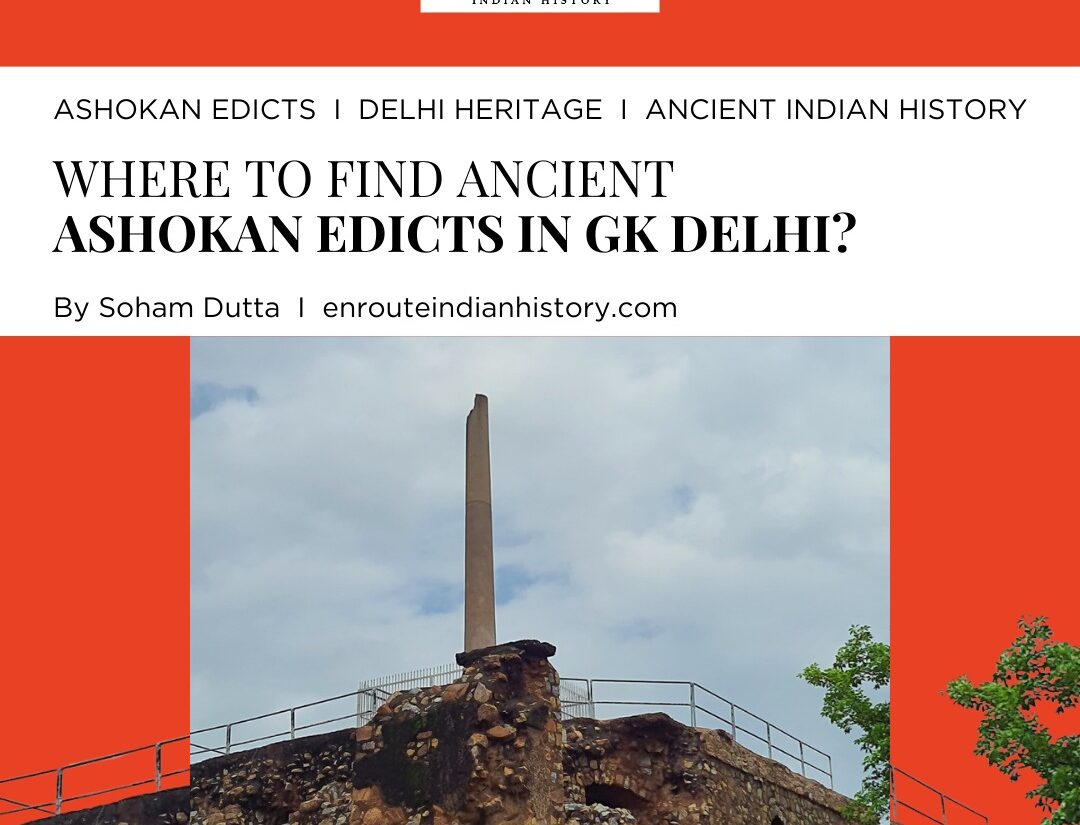

Case of Two Pillars: Minars from Remote Antiquity

(Image 1: Delhi-Topra Pillar, Image 2: Delhi-Meerut Pillar; images by Soham Dutta, August 2021 and March 2022, respectively)

Unlike the MRE of Bahapur, there are two Ashokan Pillar edicts, one in Kamla Nehru Ridge and one in Firoz Shah Kotla. Unlike MRE, these Pillar edicts are not in their in situ location; rather, they were relocated in the medieval period. According to Firishta, Firuzshah Tughluq (r. 1351–88) is reported to have erected ten ‘ancient columns’ throughout his rule Among these, there are two in Delhi. In Delhi, there is a pillar that is believed to have been transported from Topra, a village in present-day Haryana, and placed on a specially constructed structure near the royal palace at Kotla Firuzshah. The second one was transported from Mirath (modern Meerut) and installed near a hunting palace, which was located close to his capital city, Firozabad. This pillar was damaged during Farrukshiar’s rule (1713–1719 CE). The five pieces were moved to Calcutta’s Asiatic Society of Bengal, then returned and re-erected in 1887 CE.

In the Tarikh-i Firuzshahi written by Shams Siraj Afif, the process of uprooting and transporting the pillar of Topra to Delhi is described. Transportation was a difficult task and required the assistance of soldiers on horseback and foot. Various tools and tackles were used to move the pillar, which was also covered with silk, also known as sembal, to protect it from damage. Later, the silk was replaced with reeds and rawhide for further protection. To move the pillar to the river bank, a cart with 42 wheels was used, requiring the labor of 8,400 people, with 200 assigned to each wheel. The pillar was then loaded onto a large vessel. A grand pyramidal structure made of stone and lime mortar was constructed to house the pillar, with a square foundation stone placed at the bottom.

Technical details of uprooting (furūd ãwurdan ) and transportation (rawţn kardan) of the pillar, however, have been mentioned by the anonymous author of Sīrat -I Fīrūzshāh.. He mentions the packing of the pillar, the use of ropes and masonry and wooden piers used to balance the pillar during its removal, and the gardãngah (circular discs) and capstan (charkh), which accomplish this whole task.

However, a question remains: why did Firuz Shah consider the arduous task of translocation in the first place? According to Shams Siraj Afif:

“It is a fact that every great king took care during his reign to set up some lasting memorial of his power… Every other great ruler left behind numerous memorials and examples so that their names may remain in vogue till the Day of Judgement. These two wonderful pillars (i.e., the Topra and the Meerut pillars) re-erected by Firuzshah would remain such a memorial to him that it would not be possible to find another example like it in history.”

(Delhi-Topra Pillar, also described as Minar-i zarrin or Golden Pillar in Tarikh-i Firuzshahi on top of a pyramidical structure; image by Soham Dutta, August 2021)

Afif additionally reports the antiquarian interest of the Sultan, saying that upon examining the inscriptions on the pillars, the Sultan commanded the erudite Brahmins to be summoned to decode the content. The Brahmins were inherently unaware of the Brahmi script and therefore unable to decipher its contents. Nevertheless, they proceeded to inform the king that the two pillars were the gada (a type of staff) belonging to Bhim, one of the Pandavas. S.A.N. Rezavi (2009) opines that this evidence indicates the Sultan’s secular intention, which is further confirmed by his naming of the Topra Pillar as “minar-i zarrin” or “Golden Pillar,” which is a clear association with imperial and temporal authority rather than religious or moral authority.

James Prinsep’s 1837 decipherment of Brahmi marked a significant advancement in Indian epigraphy, enabling better understanding of the two pillars of Brahmi script,

Prakrit, containing six edicts.These include the following: advocating for morality to ensure both earthly and celestial happiness; urging individuals

to engage in the dhamma; emphasizing the need for personal accountability for virtuous and malevolent actions; granting rajukkas functional autonomy; documenting the release of prisoners and respite for death row inmates; and proscriptions against the killing of animals, birds, and fish. Furthermore, the Delhi-Topra Pillar encompasses the seventeenth edict, which is a retrospective statement attributed to Ashoka. In it, he provides a summary of his endeavors and emphasizes that although moral restraints and conversion by means of persuasion have been his principal approaches to effectuating change, the latter has proven to be more significant (Lahri, 2016). The fundamental tenet of these decrees was “the expansion of prosperity, well-being, and welfare by means of the dissemination of dharma,” or “Dhamma.”

(Image 1: Closer section of Delhi-Merrut Pillar located opposite Hindu Rao Hospital, Image 2: Archaeological Survey of India’s Information Plaque; Images by Soham Dutta, February 2022)

Ashoka and his Edicts: A Retrospective

Ashoka was in charge of governing a vast and diverse territory that stretched across the Indian subcontinent, as well as protecting it from both foreign and domestic enemies. In his final two decades of life, he was completely committed to the concept of ‘dharma’ or ‘dhamma’. He saw the propagation of dhamma throughout the known world as his lasting legacy to his own country and the world as a whole. It became the foundation of a larger civilization project, which, according to Patrick Ollivelle (2023), included a moral citizenry both within and outside the empire. The central theme of this project is to develop a moral philosophy that all people, regardless of social or economic status, religious, cultural, or ethical affiliations, language spoken, or political affiliation, can subscribe to and internalize in their own way. To highlight Ashoka’s uniqueness in historical records, it is necessary to quote Radhakumud Mookerjee, who wrote the first authoritative Indian work on Ashoka. He says, “In his efforts to establish a kingdom of righteousness after the highest ideals of a theocracy, he has been likened to David and Solomon of Israel in the days of its greatest glory; in his patronage of Buddhism, which helped to transform a local into a world religion, he has been compared to Constantine in relation to Christianity; in his philosophy and piety, he recalls Marcus Aurelius; he was a Charlemagne in the extent of his empire and, to some extent, in the methods of his administration, too, while his Edicts… read like the speeches of Oliver Cromwell in their mannerisms. Lastly, he has been compared to Khalif Omar and Emperor Akbar, whom he also resembles in certain respects. ” H.G. Wells, in these terms, has rightly said that amid tens of thousands of names of monarchs, “Ashoka shines, shines almost alone, a star.”.

References

- THAPAR, ROMILA. “Ashoka — A Retrospective.” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 44, no. 45, 2009, pp. 31–37. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25663762. Accessed 10 Jan. 2024.

- Rezavi, Syed Ali Nadeem. “ANTIQUARIAN INTERESTS IN MEDIEVAL INDIA: THE RELOCATION OF ASHOKAN PILLARS BY FIRUZSHAH TUGHLUQ.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, vol. 70, 2009, pp. 994–1010. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44147745. Accessed 11 Jan. 2024.

- Gaál, Balázs, and Ibolya Tóth. “SOME ‘MAJOR’ TRENDS IN AŚOKA’S MINOR ROCK EDICTS.” Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, vol. 71, no. 1, 2018, pp. 81–97. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/90019525. Accessed 9 Jan. 2024.

- Sahu, Bhairabi Prasad. “Sectional President’s Address: LEGITIMATION, IDEOLOGY AND STATE IN EARLY INDIA.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, vol. 64, 2003, pp. 44–76. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44145446. Accessed 13 Jan. 2024.

- Olivelle, Patrick. Indian Lives Series Book 1 Ashoka: Portrait of a Philosopher King. India, HarperCollins India, 2023.

- Strong, John S.. The Legend of King Aśoka: A Study and Translation of the Aśokāvadāna. India, Motilal Banarsidass, 1989.

- Lahiri, Nayanjot. Ashoka in Ancient India. N.p., Harvard University Press, 2015.

- Mookerji, Radhakumud. Asoka. India, Motilal Banarsidass, 1986.

- Chakrabarti, Dilip K.. Royal Messages by the Wayside: Historical Geography of the Asokan Edicts. India, Aryan Books International, 2011.

- Singh, Upinder. Ancient India: Culture of Contradictions. India, Aleph, 2021.

- Singh, Upinder. Ancient Delhi. India, OUP India, 2006.

- Monica L. Smith, Thomas W. Gillespie, Scott Barron and Kanika Kalra (2016). Finding history: the locational geography of Ashokan inscriptions in the Indian subcontinent. Antiquity, 90, pp 376-392 doi:10.15184/aqy.2016.6.

- February 16, 2024

- 9 Min Read

- February 7, 2024

- 5 Min Read

- January 23, 2024

- 5 Min Read