Why has Qutub Minar attracted painters and photographers over the years?

- enrouteI

- August 1, 2024

UNESCO defines ‘heritage’ as “legacy from the past, what we live with today, and what we pass on to future generations.” UNESCO World Heritage Convention works towards preserving the natural and cultural heritage. It provides State Parties with technical and professional assistance to safeguard World Heritage Sites. The aim of this convention is to encourage local participation and international cooperation in preserving world heritage sites. The 46th session of the World Heritage Committee, being held in New Delhi, is deliberating on implementation of its goals, financial aspects and modifying the list wherever necessary.

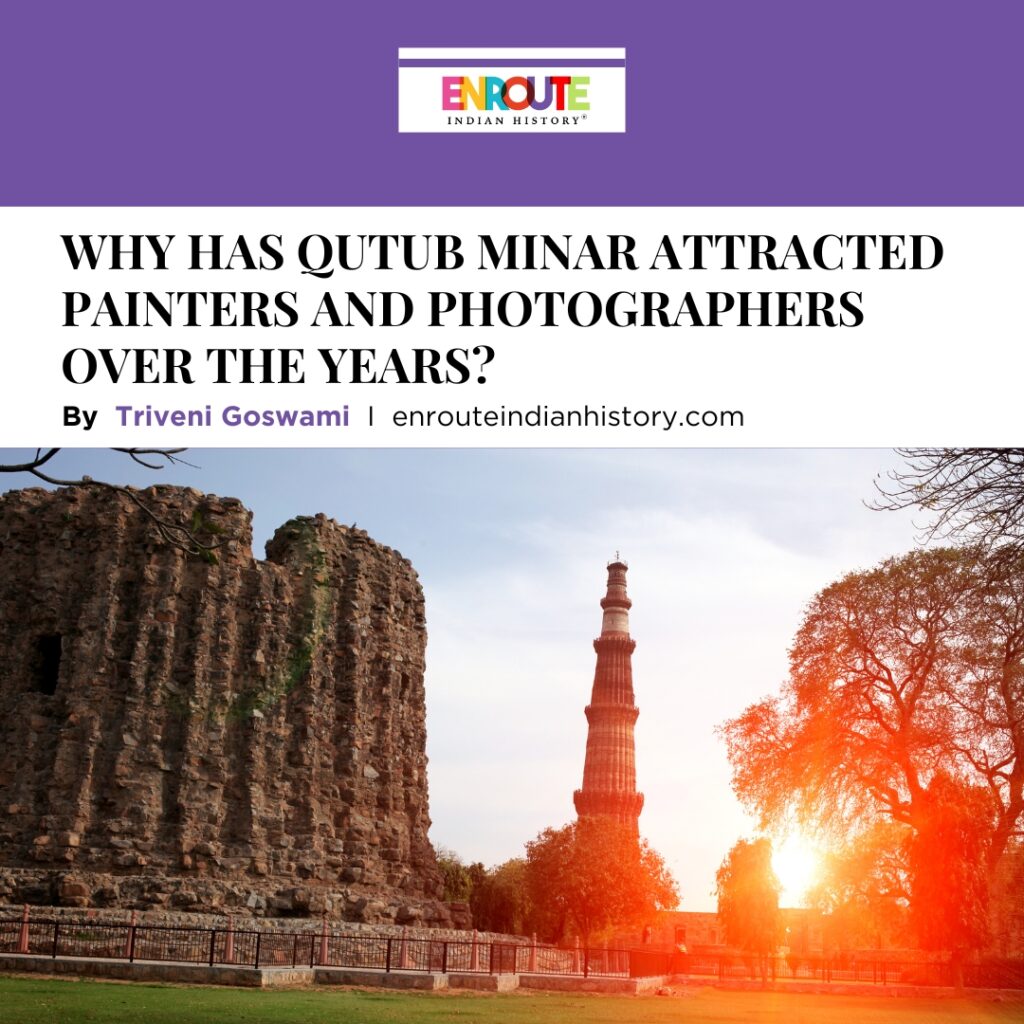

a recent picture of Qutub Minar

In 1993, the Qutub Minar was declared a World Heritage Site. The Qutub Minar complex’s assemblage of mosques, minarets, and other monuments is an outstanding testament to Islamic monarchs’ architectural and artistic achievements after they first gained authority in the Indian subcontinent in the 12th century. The complex, located on the southern outskirts of New Delhi, exemplifies the new rulers’ desire to change India from Dar-al-Harb to Dar-al-Islam using unique building types and forms. It is not surprising that UNESCO recognizes the historical significance of this monumental space. Qutub Minar’s cultural legacy dates to centuries, and it has indeed been a source of inspiration for many artists and photographers, who recognise its beauty, both architectural and cultural.

John Luard’s Painting

Painting by Major John Luard

Dating back to the 19th Century, this painting of the Qutub Minar hails from a period of art history that is of interest to many art historians. Qutub Minar, as depicted in the painting, appears as a monument of grandeur amidst ruins of a rural culture. Standing erect against the cloudy sky, it depicts a sense of historical heritage, albeit one under decay or one forgotten as it grows from a space of primitive wilderness. While paintings are subjective to the viewer’s interpretation and the views expressed above are solely the writer’s, it will not be an overstatement to say that it reflects the point of a view of a colonial observer.

Major Luard was a captain in the 16th Light Dragoons from 1825 to 1832, when he transferred to the 30th Foot. He retired as a major in 1834 and received a brevet lieutenant-colonelcy in 1838. Luard, like others in his family, was an artist. He published Views in India, St. Helena, and Car Nicobar (London, 1835), which he drew from nature and on stone, as well as History of the Dress of the British Soldier (1852), which was published by subscription. His colonial background plays a crucial role in how Indian monuments, and as an extension Indian heritage, was viewed.

Louis Rousselet’s Photograph

Photograph by Louis Rousselete

Louis Rousselet first set foot on the erstwhile colonial Bombay in 1864. The painter in him was convinced of the potential that India provided as a landscape of beauty and exploration, but he wanted to document India through the technology of a camera, as it rapidly gained popularity in Europe. As an archaeologist himself, he showed special interest in monuments. He captured the ruins of the mosque of Qutub, in the Qutub complex, as it rises to a good height, taking up most of the frame space. The group of men standing close to it, locates the monument in the concept of the exotic east, creating a sense of other. Avrati Bhatnagar in her article on Rousslet notes, “As Rousselet and other photographers like him moved through imperial networks spread across the globe, transporting camera techniques, visual frames and photographic prints; their lens often returned the gaze of the colonial picturesque back at the metropole…It captured degrees of imperial order and control by mediating the impulse to “discover” the world.”

Colonialism, Oriental Art and Oriental Photography

Stuart Hall, one of the greatest historians, called the West a “fiction.” Scholars today see Orientalism as a way for colonial rule to create a distinction between the East and the West and through that distinction, allot the West a superior status through which it gained the power of documenting the East. Oriental art played an important function in documenting the East and thereby allowing the West to frame a narrative that allowed it to colonise the east. As Edward Said noted, “To say simply that Orientalism was a rationalization of colonial rule is to ignore the extent to which colonial rule was justified in advance by Orientalism, rather than after the fact.” In painting, orientalism refers to a subject rather than a technique. The idea of an exotic primitive documentation was important to be maintained to sustain the system of colonialism.

Photo-orientalism refers to the portrayal of the East as exotic, sensual, and mysterious; bound by religious ideas; and incapable to advance and develop without outside involvement, particularly from Europe. Orientalist photography recycles existing stereotypes and prejudices to create a fictional universe that corresponds to the audience’s preconceived assumptions and affirms them of their superior status.

Photography of Qutub Minar today

Documentation of Qutub Minar has come a long way since the colonial days. A popular tourist attraction, and a beloved space to hangout for many Delhiites, Qutub Minar has stood the test of time. Freed from its colonial past, documentation of Qutub Minar in the form of photographs has taken new meanings. Photographs of Qutub Minar are a way of documenting personal histories for many Indians. Dr. Ameeta Parsuram noted in her blog, for example, how two pictures taken of Qutub Minar, sixty years apart, reflect the generational gap, emotional transformation and the changing values with time. The magnificence of Qutub Minar, standing firm, against tide of humans susceptible to mortality; allows the monument to become a marker of something more personal: the marker of time as it travels through generations. Photography of monuments like Qutub Minar are important for many archaeologists and historians to further understand its architecture and history. Research done by Mohammad Amir Khan and Osamah J. Al-sareji shows how in fact tourist pictures of monuments, including Qutub Minar, can be used to create 3-D models and automatic stereo network designs allowing better understanding of the architectural grandeur and complexities of the space.

Pictures of Dr. Ameeta and by her late brother, sixty years apart.

To conclude, UNESCO’s recognition of Qutub Minar as a World Heritage Site is important as it recognises the historical and cultural significance of the monument. It also contributes to breaking the monument away from being entrapped in a white colonial space and allows the experience of Indians and the value it serves to the Indian population, to be the central reason for its esteemed status. Even though colonial explorers helped in officially documenting information about these monuments, they were nevertheless from a point of privilege. We have come a long way since, and are weaving a new era in history, which when later studied will be revealed through the photographs the common people of India took with love and care.

References

Bhatnagar, A. (n.d.). Imperial Projects of Exploration: Louis Rousselet in India. ASAP Art. https://asapconnect.in/post/113/singlestories/imperial-projects-of-exploration

Folland, T. (n.d.). Smarthistory – Modern Art, Colonialism, Primitivism, and Indigenism: 1830–1950. Smarthistory. Retrieved July 28, 2024, from https://smarthistory.org/reframing-art-history/modern-art-colonialism-primitivism-indigenism/

Meagher, J., & King, T. (n.d.). Orientalism in Nineteenth-Century Art | Essay. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved July 28, 2024, from https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/euor/hob_87.15.130.htm

Parsuram, A. (n.d.). Qutub Minar: My Memories, Sixty Years Apart. Zikr-e-Dilli. https://zikredilli.com/f/qutub-minar-my-memories-sixty-years-apart

Qutb Minar and its Monuments. (n.d.). Ministry of Culture. Retrieved July 28, 2024, from https://indiaculture.gov.in/qutb-minar-and-its-monuments

Qutb Minar and its Monuments, Delhi. (n.d.). UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved July 28, 2024, from https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/233/

Woodward, M. L., & Hausmann’s, E. (n.d.). Orientalism in Nineteenth-Century Photography. Photorientalist. Retrieved July 28, 2024, from https://www.photorientalist.org/about/orientalist-photography/

Image Sources (Chronologically)

https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/233/

https://asapconnect.in/post/113/singlestories/imperial-projects-of-exploration

https://www.tallengestore.com/products/qutab-minar-delhi-major-john-luard-vintage-orientalist-paintings-of-india-large-art-prints

https://zikredilli.com/f/qutub-minar-my-memories-sixty-years-apart