Article Written By EIH Researcher And Writer

Rayana Rose Sabu

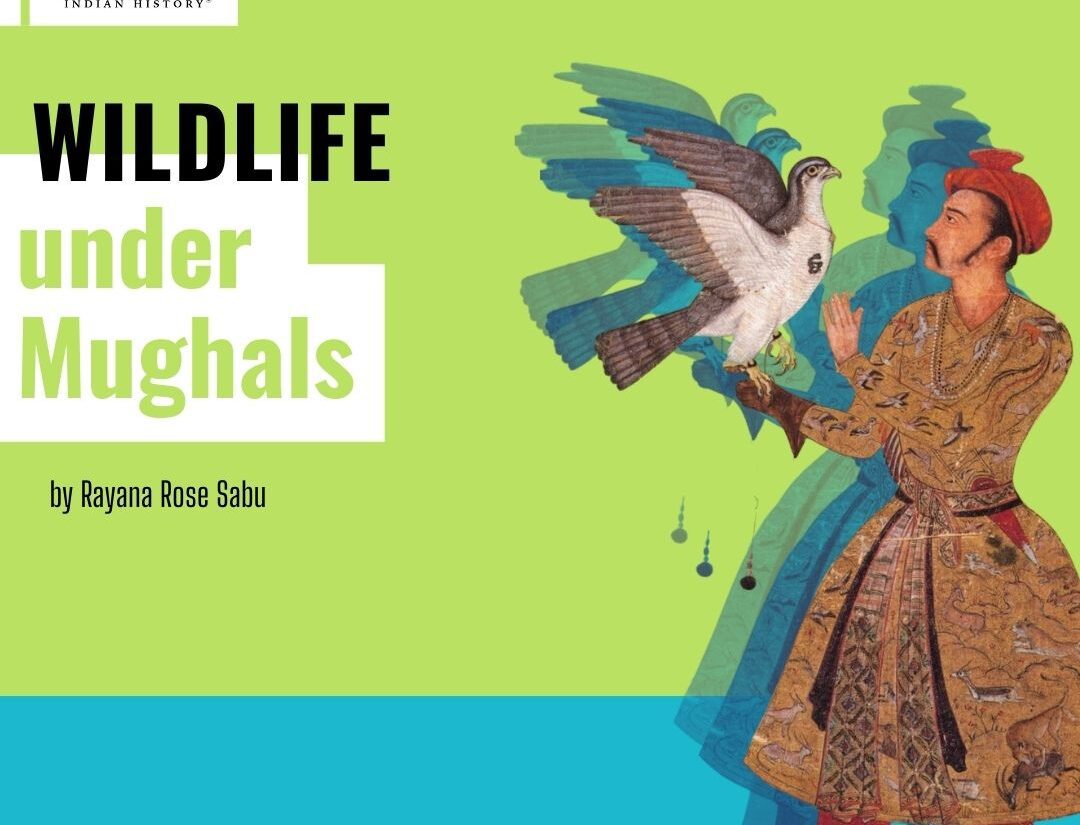

The Mughal Empire, which reigned over parts of India from the early 16th century to the mid-nineteenth century, was recognised for its encouragement of the arts and architecture and administrative and military achievements. India enjoyed an era of relative peace, stability, and prosperity under the reign of the Mughal Empire. The rulers were generous patrons of the arts, fostering a thriving culture blending the finest Indian, Persian, and Islamic traditions.

The Mughal Empire also had a profound impact on Indian subcontinent wildlife. The emperors were enthusiastic hunters and kept huge menageries of exotic animals. It began with Babur’s remarkable descriptions of natural phenomena, particularly Hindustan flora and animals. The Mughal Emperors’ comments on nature culminated in the Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri. These narratives are distinguished by an overtone of enthusiasm for the beauty they discovered in things, and they did not hesitate to voice their dislike for an ugly-looking animal.

But it was emperor Jahangir who had a special connection with animals that was deep and forged even before his birth. According to legend, while Jahangir’s mother had pregnancy complications, Akbar pledged never to hunt with cheetahs on Fridays. This promise proved successful, and Jahangir was born. Jahangir showed extraordinary attention to detail and was a great observer, even as a young boy. He utilised these traits to learn more about the natural world around him. The young prince was fascinated with animals and commissioned some of the most meticulous paintings of rare animals and birds from his court artists. These paintings of exotic animals and birds were some of the first ones created in India. Jahangir had a renowned atelier, and Mansoor, who produced the most exquisite miniature paintings, was one of the most favoured artists. The emperor recorded detailed descriptions of the creatures he came across in his biography.

For instance, in 1620, when Jahangir visited Kashmir, he encountered a brown dipper which he described in his biography Tuzk-i-Jahangiri:” In this stream, I saw a bird like a saj. It dives, remains underneath for a long time, and comes up from a different place. I ordered them to catch and bring two or three of these birds so that I might ascertain whether they were waterfowl or web-footed or had open feet like land birds. They caught two..one died immediately, and the other lived for a day. Its feet were not webbed like a duck’s. I asked Nadirul-asr Ustad Mansur to draw its likeness”

In actuality, it was a dodo, and this was one of the earliest and most accurate depictions of the now-extinct bird. Jahangir also enjoyed gathering exotic creatures. One of his nobles, Mir Jafar, immediately bought a zebra from some Turks and gifted it to Jahangir. There are tales of how the zebra was mistaken for a horse with painted stripes and how attempts were made to scrub the stripes off before realising the animal was born with them. Jahangir made a lovely miniature before giving the zebra to the Shah of Iran.

Perhaps, the most peculiar story involving Jahangir and animals consists of a pair of Sarus cranes he owned named Laila and Majnu. They were given to the Mughal court as chicks, and five years later, they mated. When Jahangir learnt they had laid eggs, he was thrilled. His detailed observation of their nesting behaviours revealed that the male stood watch while the female sat alone with the eggs. Around dawn, the male would scratch the female’s head with his beak and switch places with the female. He observed that the male bird carried the hatchlings upside down when the eggs hatched, so he kept the male apart until it was determined ‘that its action had been affectionate’. The tales never end; there was a time when he interrupted a snake feasting on a rabbit because he wanted to observe it closely, so he asked his scouts to pick up the snake, and the startled reptile dropped the rabbit. Unfazed, Jahangir directed his scouts to stuff the rabbit in the snake’s mouth. He reports that ‘no matter how hard they tried, they couldn’t get it back in; in fact, they used so much force that they tore a corner in the snake’s mouth’.

The emperor’s experimentation did not stop. He was fascinated by animal reproduction and crossed-bred goat species, Markhor and Barbari. He made insightful observations regarding the offspring, noting that while regular goat kids would bleat and cry, the crossbreeds did not, and they acted highly independent. Still, he was never sentimental about them and looked forward to eating them. Jahangir was fascinated by wildlife and often performed autopsies on animals to understand their anatomical structures better. In one such incident, he did an autopsy on a lion to determine the source of its bravery. He found that, unlike other animals, lions’ gallbladders were inside the liver. He concluded that this was likely the secret of the animal’s bravery.

The emperor did, however, have a compassionate side, and he forbade the slaughter of animals on Thursdays and during Jain festivals. Jahangir erected a tomb for his pet antelope, the Hiran mandir, and the Haathi Mahal (elephant palace) for his elephants to spend time after they retired from combat service. He loved his elephants so much that when he saw them shivering in the frigid Yamuna water in December, he ordered his swimming pool to be filled with hot water and allowed his elephants to bathe in it.

Jahangir’s observation skills had surpassed those of his scouts and gamekeepers, and his abiliy and perseverance gained notoriety. He was reportedly the happiest among kids and animals. After he died in 1627 and Shah Jahan succeeded him, miniature paintings lost popularity, and Shah Jahan had no particular fondness for animals. But Jahangir’s memory endures due to the anecdotes contained in the Tuzk-I-Jahangiri and the miniatures that have traversed the globe.

SOURCES

-Jain, A. (2019, April 22). Emperor Jahangir: The Naturalist. PeepulTree. https://www.peepultree.world/livehistoryindia/story/people/emperor-jahangir-indias-first-naturalist

-Khan, E., & Parwez, M. (n.d.). Man and Wildlife in Mughal India : Jahangir and Nilgaw hunt. Vidyasagar University Journal of History , 2, 2013–2027. Retrieved March 3, 2023, from http://inet.vidyasagar.ac.in:8080/jspui/bitstream/123456789/1818/1/10.%20Enayatullah%20khan%20and%20Mohammad%20Parwez.pdf

–ANGEL. (2018, December 1). Salim and his pets. History and Chronicles. https://angel1900.wordpress.com/2018/12/01/prince-salim-and-pets/