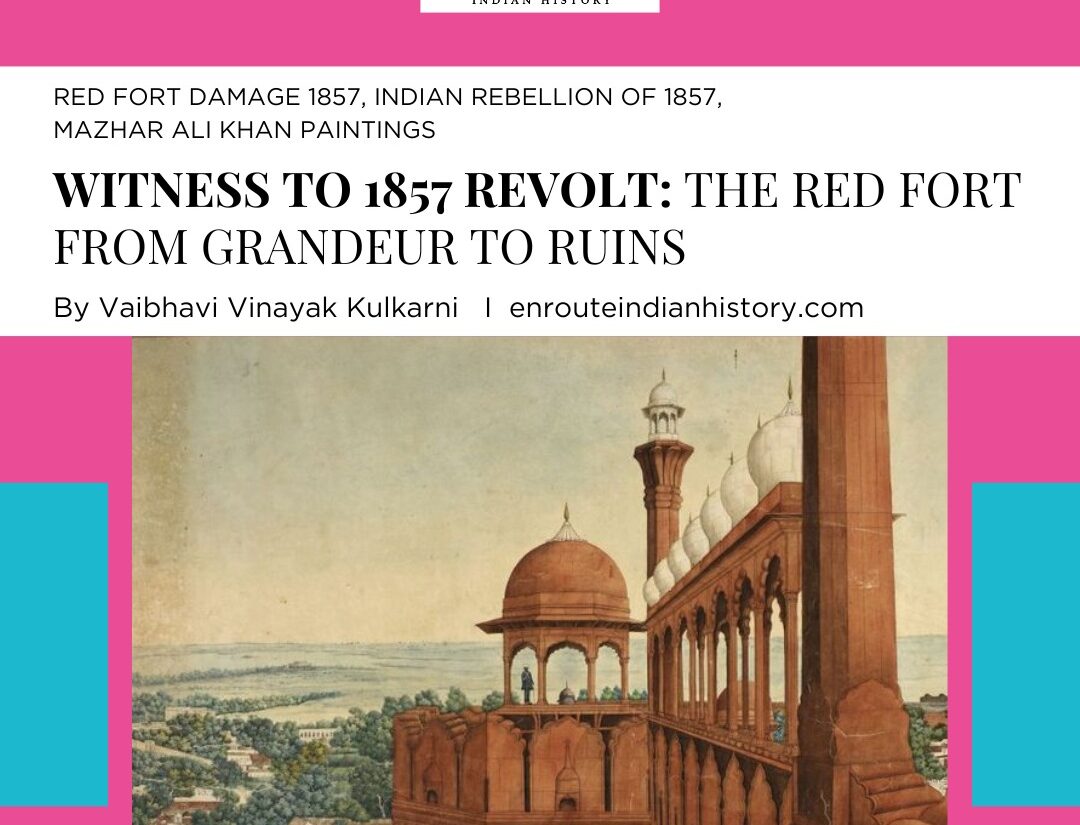

The Indian Revolt of 1857, also known as the Sepoy Mutiny, was a pivotal moment in Indian history that marked a significant upheaval against British colonial rule. This revolt had far-reaching impacts on various aspects of Indian society, including its architectural heritage. One of the most emblematic sites affected by the rebellion was the Red Fort in Delhi. The Red Fort, a symbol of Mughal grandeur and architectural brilliance, witnessed substantial damage during this period. The historical painting of Mazhar Ali Khan, an artist of that era, provides a poignant visual documentation of the Red Fort from 1846. The panorama painting helps us to understand, before and after the 1857 revolt. One can observe the historical and architectural changes brought about by the conflict and subsequent British Raj.

Section of Panorama of Delhi Painting By Mazhar Ali Khan (Source: British Library)

Red Fort: History and Significance

The Red Fort, or Lal Qila, is an iconic symbol of India’s rich history, architectural brilliance, and the enduring spirit of its people. The Red fort, also known as the Qila-e-Shahjahanabad and the Qila-e-Mubarak, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan built the Red Fort in 1639, it took over a decade to complete it in 1648. It has served as the main residence for the Mughal emperors for nearly 200 years. This majestic fort, constructed from red sandstone, epitomizes the zenith of Mughal architectural innovation and grandeur. The Red Fort is renowned for its stunning and intricate architectural elements. The fort complex includes the Diwan-i-Aam (Hall of Public Audience) and Diwan-i-Khas (Hall of Private Audience), which exemplify the Mughal aesthetic with blending of Persian, Timurid, and Indian architectural styles. The fort also formerly included magnificent gardens, marble structures and pavilions, reflecting the Mughal emphasis on elegance and splendor. Beyond its architectural splendor, the Red Fort holds immense historical significance. It was not merely a military fortification but a center of governance, culture, and artistic expression. The fort was a potent symbol of Mughal power and wealth, embodying the empire’s zenith.

Red Fort Complex in present (Source: UNESCO)

Mazhar Ali Khan: Visual Chronicler of Late Mughal Delhi

Mazhar Ali Khan is an exceptional topographical artist from late Mughal Delhi. He is renowned for his precision and dedication to capture authentic views of historical sites. Unlike many artists of his time, he was known for visiting actual locations to create his sketches rather than relying on the works of predecessors. This approach allowed him to produce highly accurate and detailed depictions of the city’s monuments and landscapes. Mazhar Ali Khan’s artworks are invaluable historical documents that capture the architectural splendor and grandeur of Mughal Delhi. Sir Thomas Metcalfe, the President of the Archaeological Society of Delhi, may have acquired or commissioned Mazhar Ali Khan and his Studio to create a comprehensive visual record of Shahjahanabad (Old name for Delhi) and its significant structures. This collection includes 125 paintings, capturing both major monuments and lesser-known mosques and tombs. Metcalfe’s extensive research and accompanying writings further enriched these visual works, providing a detailed historical context.

Section of Panorama of Delhi Painting By Mazhar Ali Khan (Source: British Library)

The Delhi Panorama by Mazhar Ali Khan

One of Mazhar Ali Khan’s most notable works is the large-scale panorama of Delhi, painted and signed by him on November 25, 1846. This nearly five-meter-wide painting offers a 360-degree view from the southern exterior tower of the Lahore Gate of the Red Fort. The panorama masterfully integrates various viewpoints into a cohesive whole, displaying remarkable control of linear and aerial perspective. Mazhar Ali Khan’s panorama reveals key aspects of the Delhi palace, including the Diwan-i-Aam (Hall of Public Audience) and the Diwan-i-Khas (Hall of Private Audience). The artwork illustrates the red stone railing in the courtyard, which separated the nobles and privileged from the general public. It also provides insights into the city of Shahjahanabad.

This work is especially significant as it captures the appearance of the Red Fort and its surroundings in the 1840s, a decade before much of the area was destroyed in the 1857 uprising. These paintings not only offer a glimpse into the past but also serve as a testament to the resilience and enduring legacy of Delhi’s architectural heritage.

Section of Panorama of Delhi Painting By Mazhar Ali Khan (Source: British Library)

Diwan-i -Am and the jharoka, in the Delhi palace, by Mazhar ‘Ali Khan, c.1840. (Source: The Delhi Palace in 1846: a panoramic view by Mazhar Ali Khan)

The 1857 Revolt: The Red Fort and the Mughal Emperor

The 1857 Revolt, also known as the Indian Rebellion of 1857, was a major uprising against the British East India Company’s rule in India. It marked a crucial turning point in Indian history, with widespread participation from various segments of society, including soldiers, peasants, and local rulers. The revolt began as a Mutiny of Sepoys or Indian soldiers, in the British East India Company’s army. The immediate cause of the mutiny was the introduction of the new Enfield rifle, which required soldiers to bite off the ends of lubricated cartridges believed to be greased with cow and pig fat, offending both Hindu and Muslim religious practices. Among the central locations during this rebellion was Delhi, where the Red Fort and the Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar played significant roles. The Mughal Empire was significantly weakened by the mid-19th century, though the Red Fort still held immense symbolic power.On May 11, 1857, the early morning peace at the Red Fort was shattered by the sounds of rebellion. Bahadur Shah Zafar, the 82-year-old Mughal emperor was caught off guard, and found himself at the centre of a burgeoning revolt. On the afternoon of May 11, the rebel soldiers reached the Red Fort and persuaded Bahadur Shah Zafar to lead them. Despite his old age and lack of real political power, Bahadur Shah Zafar became a figurehead for the rebels. Under his nominal leadership, Delhi became a key stronghold for the rebels. The Red Fort, with its grand halls like the Diwan-i-Aam (Hall of Public Audience) and Diwan-i-Khas (Hall of Private Audience), turned into the headquarters of the revolt. However, this phase of revival was short-lived.

The Siege and Aftermath

The British quickly organized a counteroffensive as recapturing Delhi was crucial to regaining control over the rest of India. By September 1857, after several months of fierce fighting, British forces managed to recapture Delhi. Bahadur Shah Zafar was captured, tried, and exiled to Rangoon (now Yangon, Myanmar) where as the British executed his sons. The Delhi city sustained significant damage during the siege. The Red Fort itself witnessed significant destruction, and many of its beautiful structures were damaged or demolished.When the British stormed the city, widespread plunder and destruction ensued. Soldiers were allowed three days of unrestricted looting, taking valuables from the Red Fort, including jewels, weapons, royal clothing, and in situ marble slabs and inlay work. The copper-gilt domes of the Diwan i Khas, the Musamman Burj and the Moti Masjid were auctioned off. Many looted items made their way to England, as numerous British soldiers and officers chose to retire after the revolt ended, taking their spoils with them. Just as British gentlemen had taken historical artifacts home in the early nineteenth century as souvenirs of their Indian experiences, veterans of the 1857 mutiny brought back trophies of their conquest. Several of these trophies ended up in British museums. Among the most famous were rare pietra dura panels from the Red Fort’s Hall of General Audience, including the top central panel depicting Orpheus playing his lute, surrounded by wild animals. Captain John Jones took these panels in 1857, and they were later bought by the British government for 500 pounds when Jones returned to England. These panels eventually became part of the Indian artifacts collection at the Kensington Museum, now known as the Victoria & Albert Museum. Significant alterations were made to the city and its quarters. The Red Fort, a symbol of resistance, was drastically changed. Many buildings deemed unimportant or unusable were demolished, and the grounds were leveled. Debris from these clearances was used to create a glacis around the Fort walls. Outside the Fort, buildings within a 450-yard limit were cleared, resulting in dramatic changes. Only two buildings, the Rang Mahal and the Chota Rang Mahal (Mumtaz Mahal) but without their court, have survived the demolitions of 1858. By the end of this campaign of confiscation and demolition, Delhi was left a battered and mutilated city.

(Source: Commemorating and remembering 1857: The revolt in Delhi and its afterlife)

Kashmiri Gate after 1857 (Source: Commemorating and remembering 1857: The revolt in Delhi and its afterlife)

The 1857 Revolt and its aftermath profoundly reshaped the architectural and cultural landscape of Delhi, leaving the Red Fort a stark symbol of both the rebellion’s fierce resistance and the devastating consequences of colonial reprisal. The enduring legacy of this period serves as a poignant reminder of the resilience and enduring spirit of India’s historical heritage.

Bibliography:

- Nayanjot Lahiri (2003) Commemorating and remembering 1857: The revolt in Delhi and its afterlife, World Archaeology, 35:1. pp. 35-60.

- Losty J.P. The Delhi Palace in 1846: a panoramic view by Mazhar Ali Khan.

- The Red Fort and its surroundings. Booklet by World Monuments Fund’s Sustainable Tourism Initiative.

- https://www.deccanherald.com/india/red-fort-the-symbol-of-the-1857-rebellion-1136141.html

- https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/delhi/filling-the-red-fortamp39s-blanks/articleshow/11162894.cm

- May 29, 2024

- 11 Min Read

- May 29, 2024

- 8 Min Read