Woman and Indian Theatre: Shaping Identity and Narrative

- EIH User

- August 29, 2024

Indian theatre has long been a powerful medium for storytelling, cultural expression, and social commentary. Over the centuries, it has evolved through diverse traditions, from ancient Sanskrit drama to contemporary experimental performances. Yet, the role of women in Indian theatre has undergone a transformative journey, mirroring the broader societal shifts in gender dynamics. Historically, women in Indian theatre were often sidelined or absent. In traditional performances like Kathakali and Yakshagana, women weren’t just sidelined—they weren’t allowed to perform. Men played female roles, reflecting a society that kept women out of the limelight and confined them to domestic roles. As Poile Sengupta poignantly captures in her play “Mangalam”, “Because a woman has patience, she is not allowed to speak, and she never learns the words.”

Throughout history, male writers have often depicted women’s roles in Indian theatre in ways that served their narratives, shaping female characters to fit particular ideals or evoke specific emotions. Even when women were central characters, as in Kalidasa’s “Abhijnana Shakuntalam” or the ancient Tamil epic “Cilappatikaram”. Their roles were often crafted to evoke pity—a sentiment that men in a phallocentric society are traditionally taught to fear.

Women in these stories were frequently portrayed in relation to men, their identities defined by their romantic or sexual relationships. This portrayal reinforced a limited view of women’s roles and experiences, reducing them to objects of male desire or symbols of virtue, rather than fully realized individuals with their agency and complexities. However, the narrative began to shift as women increasingly asserted their presence on the stage. From being marginalized, they have become central figures in feminist movements within Indian theatre, challenging and redefining the portrayal of gender, identity, and power.

From IPTA to Feminist Theatre

The 1940s saw the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) breaking new ground, offering a dynamic stage where women could shine as performers and directors, altering women’s representation in Indian drama. Many people’s journey into IPTA was sparked by their political activism, which later transitioned into cultural activism, giving rise to powerful female narratives in Indian theatre. Dina Pathak, for example. Originally a social activist, she viewed her artistic contributions as “the work of manure”—essential nourishment for societal growth. Similarly, Reba Roychoudhury’s memoir paints a vivid picture of IPTA’s vibrant environment—brimming with “laughter, galp (stories), dance, play, writing, alochna (discussions), and reading”—which fueled her resolve to challenge societal norms.

This supportive and progressive space of IPTA empowered many women to use drama as a powerful tool for self-expression and identity exploration, solidifying their place in women-led theatre movements in India. By bringing their own experiences to the stage, they connected deeply with audiences and used their cultural backgrounds to shape compelling characters, emphasizing the importance of women’s representation in Indian drama. Their performances became a platform for asserting their identities and advocating for social change, aligning with the broader goals of gender activism in Indian theatre “Sarphire” IPTA

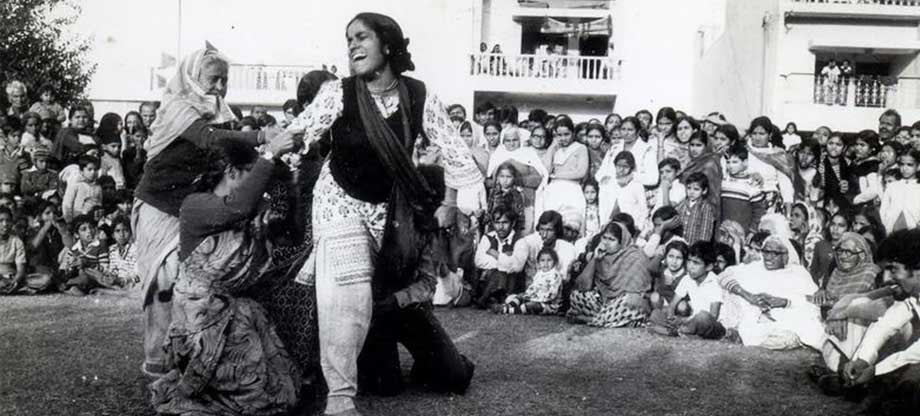

Feminist theatre in India emerged as a bold counter to patriarchal norms in both society and the arts. It challenged traditional narratives, marking a significant shift in female narratives in Indian theatre. This genre, which grew alongside the street theatre movement, used performance techniques to push for social justice. A pioneering example of this movement was the Jan Natya Manch, founded by Safdar Hashmi in 1973. Their street play, “Aurat” (1979), took on critical issues like sati, domestic violence, and dowry. Addressing not only pressing issues but also reimagining traditional myths, offering fresh perspectives on epic figures like Sita and Savitri from a woman’s viewpoint.

Women Playwrights Making Waves in Indian Theatre

Emerging female narratives in Indian theatre have been strongly represented by figures like Usha Ganguli and Mahasweta Devi, who have brought fresh, fearless perspectives to the stage. Mahasweta Devi, in particular, delves into the complexities of societal conflict with plays such as “Mother of 1084”, which vividly portrays a mother’s profound grief during the Naxalite movement. Her other works, including “Aajer”, “Urvashi O’ Johnny”, “Bayen”, and “Water”, showcase her unwavering commitment to addressing social injustices and giving voice to marginalized communities, highlighting the vital role of women’s representation in Indian drama.

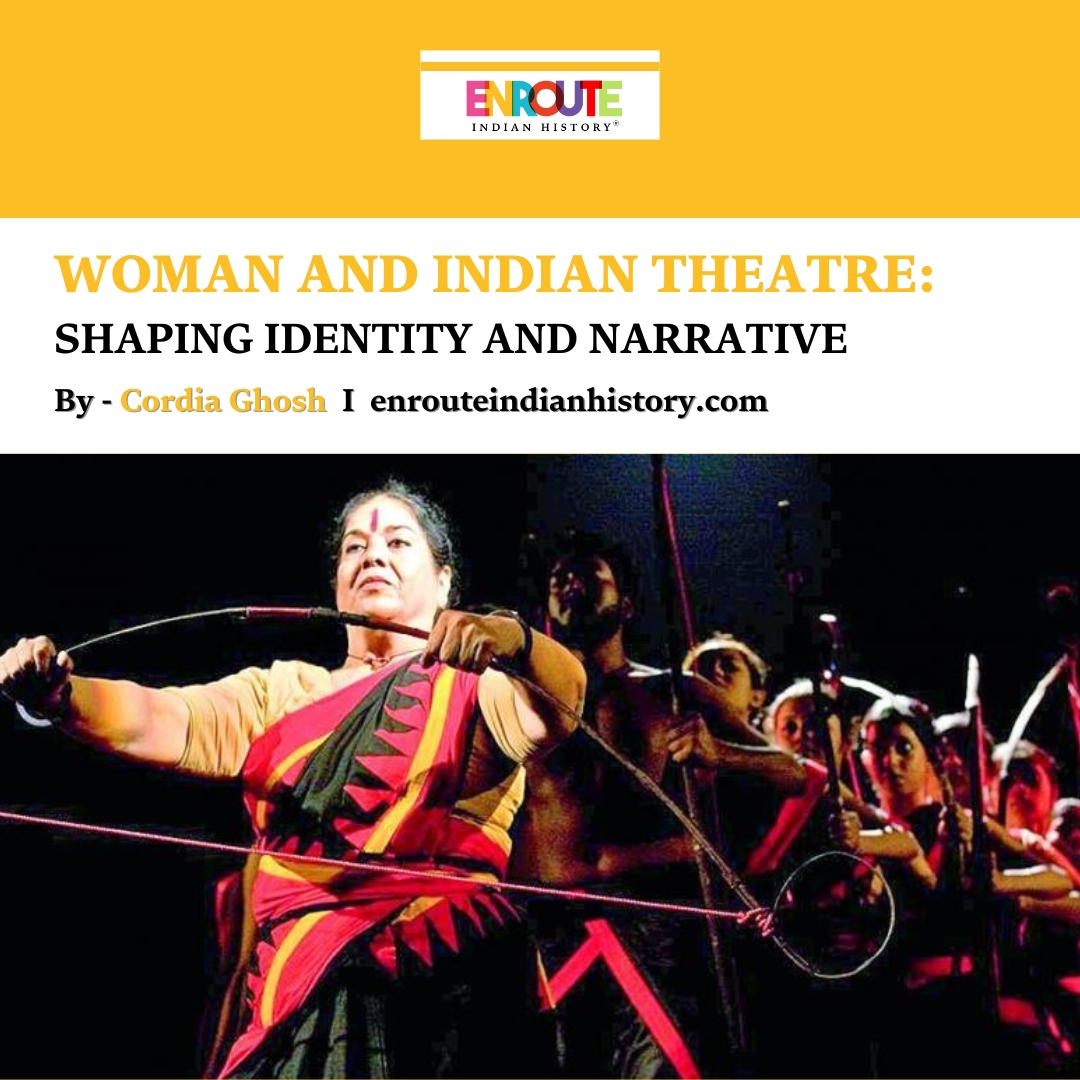

Scene from Usha Ganguly’s play Chandalika.

Tutun Mukherjee’s anthology, “Staging Resistance: Plays by Women in Translation”, sheds light on the uphill battle faced by women playwrights. Mukherjee reveals how a male-dominated theatre scene often pushed women’s voices to the sidelines and limited their creative freedom. Historical barriers, from educational denial to male-dominated print culture, have constrained women’s roles in Indian theatre.

Yet, despite these challenges the landscape of women’s theatre is thriving. Festivals and workshops hosted by groups like Yavanika in Hyderabad, Prithvi Theatre in Mumbai, and Rangakarmee in Kolkata have become vital platforms for celebrating Women playwrights in India. The National Women’s Theatre Festivals in Mysore and beyond further this momentum, spotlighting female playwrights and their impactful work.

Usha Ganguli’s ”Antaryatra” (2002) uses her own experiences to illuminate the struggles of actresses, while Jyoti Mhapsekar’s “Beti Aayee” addresses discrimination against the girl child with an all-female cast. Geetanjali Shree’s “Umrao” (1993), adapted from Mohammad Hadi Ruswa’s novel, critiques the stereotypical portrayal of courtesans. Tripurari Sharma’s “Lado Mausi” and Madhushree Dutta’s “Sundari” explore the intersection of gender and performance, while B. Gauri’s “Aur Kitne Tukde” delves into the trauma of partition through female experiences. Born from the experimental theatre movement of the 1960s and the feminist political upheaval, feminist theatre in India has redefined traditional structures, emphasizing non-linear narratives and open-ended conclusions to highlight women’s unique perspectives

Gendered Spaces in Indian Theatre

Indian theatre has long been a stage dominated by male heavyweights like Girish Karnad, Vijay Tendulkar, and Badal Sircar. When it comes to English-language drama, figures like Pratap Sharma, Asif Currimbhoy, and Mahesh Dattani have traditionally held the spotlight, leaving female playwrights in the shadows. Yet, this isn’t the whole story. Women like Bharati Sarabhai, with her impactful plays “The Well of the People” and “Two Women”, have made their mark, and in recent years, voices such as Mrinalini Sarabhai, Uma Parameshwaran, Shanta Gokhale, and Poile Sengupta have brought fresh perspectives to the stage, significantly contributing to feminist theatre in India.

But why the disparity? Why are women playwrights in India not given their due?

The issue reflects broader concerns about women’s representation in Indian drama and how gendered spaces in Indian theatre often marginalize female voices.

In an interview with Lakshmi Subramaniam, Dattani addressed the scarcity of women playwrights in modern Indian theatre. He noted that “women playwrights write about strong feminine concerns or simply write about women for no political reasons (same as male playwrights write about men without really thinking about it).” However, “theatre companies prefer to do plays with a male protagonist,” which may explain the “less female representation among visible playwrights.”

Many men who manage theatre spaces often dismiss women playwrights because they struggle to relate to narratives told from a female perspective or fail to take them seriously. This lack of understanding has hindered the careers of many women aspiring to make their mark in playwriting, further exacerbating the challenges within women-led theatre movements in India. The gap between male and female representation in theatre mirrors the broader legal and social support—or lack thereof—for women. It wasn’t until 1961 that anti-dowry laws were introduced, and domestic violence only became legally punishable in 1983. These legal milestones highlight the ongoing need for societal change to support women’s empowerment.

Fast forward to today, and women’s role in Indian theatre is transforming. It’s not just about the performances; it’s about balancing feminist ideology with theatrical artistry. Sharanya Ramprakash’s “Akshayambara” is a striking example of this evolution. By taking on the role of Duryodhana, a traditionally male character, Sharanya doesn’t merely step into a male-dominated space; she redefines it, challenging conventional gender norms without the need for disguising her femininity. Ramprakash’s approach underscores a powerful statement:

“When I come on to the stage, and say I am Ravana, people should be ready to go with that,”

Feminist theatre, as Susan Basnett puts it, is all about demanding equal pay, education, and opportunities while challenging outdated social norms and practices. It’s a space where women are rewriting the rules, turning traditional narratives on their heads, and crafting stories that reflect their unique experiences. The Coming of Age, Women Playwrights Shaping Indian Theatre

The spotlight on women playwrights in India is a more recent and thrilling development. Women like Dina Mehta, Manjula Padmanabhan, and Poile Sengupta have burst onto the scene, shaking up the traditional narrative and bringing fresh perspectives to the stage.

Dina Mehta, the Mumbai-based trailblazer, has made a splash with plays like “The Myth Makers” and “Brides Are Not for Burning”. The latter, which snagged the BBC’s worldwide competition prize, dives deep into issues of gender-based violence and discrimination. Manjula Padmanabhan, known for her groundbreaking play “Harvest” (which won the Onassis Prize), spans genres from comic strips to novels, tackling themes of objectification and societal norms. Poile Sengupta has made her mark with her debut play “Mangalam” and other notable works like “Keats Was a Tuber”, adding rich layers of children’s literature and themes of migration and identity to the theatrical world.

These pioneering women have expanded the theatrical canvas, moving beyond the confines of domesticity to explore complex female experiences and challenge outdated norms. They’ve redefined feminist theatre, presenting strong, multifaceted female characters and pushing beyond traditional narratives. With women playwrights and directors gaining prominence, their work is reshaping the status quo. The stage is now set for a new era—one where gendered spaces are being redefined, and women are taking centre stage in narrating their own stories

References:-

https://www.indiatimes.com/explainers/news/feminist-theatre-in-india-562063.html

https://www.yourarticlelibrary.com/essay/rise-of-womens-theatre-in-india/24346#google_vignette

https://www.critical-stages.org/3/

https://www.hercircle.in/hcm/Engage/D/854484F8-0AE5-416D-A1F8-2AD0010B88C3.JPG

https://thetheatretimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/DSC_0012948715-900×598.jpg

https://images.deccanchronicle.com/dc-Cover-jeir52gqcad2dsguijedf5nok7-20181020224648.Medi.jpeg