21 Lamps and Deer skin : How unique shadow puppetry tells the story of Ramayana

- EIH User

- October 29, 2023

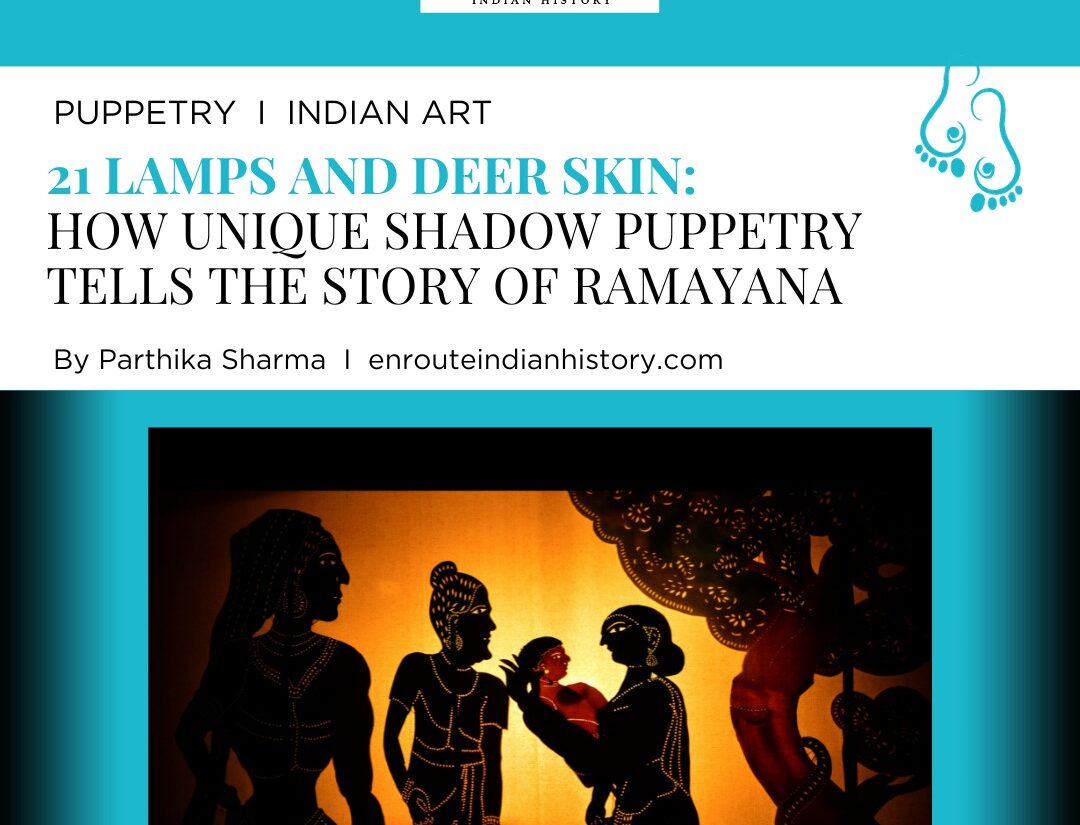

The setting is an intimate dark theatre at the edge of Bhadrakali Temple. A makeshift screen is hung up using a black cloth on the bottom and a white cloth on the top. On a long Jackwood plank behind this curtain, twenty-one half-shells of coconuts with cotton wicks are placed, filled with coconut oil. One by one, leather puppets are pulled out from a basket – Rama, Laksmana, Sita, Surpanakha, Ganesha, numerous demons- and are stacked on one side.

Then, suddenly, the air is filled with sounds of cenda drums emanating from the temple. The oracle-priest emerges, advancing with deliberate steps that jingle the bells on his ankles, his belt, and the curved sword he is holding high above his head. An assortment of musicians, a temple lamp bearer, authorities, and spectators follow him. His ice-white hair and bright crimson skirt flashing in the light of kerosene lamps, he becomes possessed by Bhagavati, his prophetic shrieks scarcely audible above the thunderous drumming behind him.

The procession circles the drama house three times, and then the oracle-priest halts, performing a brief, jerky dance and uttering cries, he showers the spectators with rice. He renders a final offering of rice to the principal puppeteer, who then receives the heavy brass temple lamp and lights the wicks. The screen illuminates with hues of orange, and two Brahmin puppets emerge, dancing jerkily around Ganesha and ringing bells in imitation of the oracle-priest.

Traditionally puppetry in India can be divided into four forms based on the style of manipulation – glove, rod, string and shadow. Tholpavakoothu falls under the second category.

By Mullookkaaran – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, Source: Wikimedia Commons

Tholpavakoothu shadow art is a ritualistic performing art that is prevalent in Kerala’s northern regions such as Palakkad and Malappuram. In Malayalam, ‘thol’ means leather, ‘pava’ means puppet, and ‘koothu’ means play, and Tholpavakoothu uses leather puppets to illustrate the Kamba Ramayanam. It is a form of Indian shadow puppetry which is performed using twenty-one oil lamps mounted on a specially curved wooden beam called ‘vilakku madam’. Traditionally, the performances take place during the Pooram season from January through May; usually beginning at midnight and continuing until dawn. Depending on the temple where it is performed, the performance may take 7, 14, 21, or 41 days and involves 120 to 150 puppets.

The leader of the troupe is respectfully referred to as Pullavar (scholar), a moniker that many indigenous shadow puppeteers from Kerala have begun adopting as their last name. The recitation of slokas is a part of the performance, and the performers are expected to know the meanings of over 2100 slokas before they take the stage. In some temples, the cultural performance is accompanied by instruments such as the chenda, ezhupara, ilathalam (metal instrument), and maddalam.

Before the performance begins, audience members give the puppeteers their names, promise donations (invariably one rupee apiece), and describe any issues they are eager to have remedied. Later, at some point in the show, the puppeteers would stop their narration to read each of those names and sing a verse for each patron who had donated one rupee, soliciting the blessings of the goddess Bhagavati and Sri Rama on their behalf.

On a long Jackwood plank behind this curtain, twenty-one half-shells of coconuts with cotton wicks are placed, filled with coconut oil.

By Arayilpdas at ml. Wikipedia, CC BY 3.0

The Goddess who was born from poison : Bhadrakali

Tholpavakoothu puppetry is not primarily performed for an audience, but rather as a ritualistic worship of the goddess Bhadrakali. It is preceded by several rites performed at the main temple to summon the goddess Bhadrakali to witness the story. This is established based upon a legend- “Brahma had blessed a demoness who gave birth to a son named ‘Darika’. Darika grew to be so strong that he troubled hermits and sages, who distressed, prayed to Lord Shiva for assistance. Shiva used the poison “Kalakoota” to create the goddess Bhadrakali. The battle between them went in for days. Rama and Ravana were engaged in a furious battle at the same time, and Bhadrakali was unable to witness the fight, and thus the Ramayana was performed for her.

A 17th-century wooden idol of Bhadra Kali from Kerala

The setting of Tholapavakattu

The practitioner of the art must be an adept carver with the ability to carve semi-transparent or opaque models of people, fabled animals, etc. from animal hide. As deer is revered in Hindu mythology and the Ramayana is regarded as a sacred story, it was essential to use deer skin to craft the Tholpavas. Only rulers from the Kshatriya clan had the right to hunt the deer for food and they deployed the leftover hide for making puppets for tholpavakoothu.

In the present day, buffalo skin or goat skin is used. The puppet is sculpted by punching small holes in the leather with chesiles and an hammer and then attaching it vertically to a bamboo rod. Different carving techniques are employed in the creation of puppets, including Veeralipattu for king robes worn by Rama and Ravana, Nakshatrakothu for Lakshman’s puppet, Nelmanikothu, in which both sides are carved, and Chandrakalaroopam for the moon’s shape. The deerskin puppets were black and white but goatskin being very thin allows one to experiment with colors.

Five different categories of Tholpavakoothu puppets can be distinguished: sitting puppets with only one movable hand, standing puppets with just one movable hand, walking puppets with both movable legs, lying puppets, and war puppets with both movable hands and legs. Agarbhathi’s powder, also known as telli powder, is thrown on the oil lamp flames during the war scene to produce special effects that simulate a conflagration on screen.

Prepared stage at a Koothumandam Source: Wikimedia Commons

Tholpavakoothu is performed in varied spaces in temples – corridors, courtyards, and built structures. However, the primary spot for the shadow art is a separate structure facing the temple, a permanent shadow theater, known as the ‘Koothumadam’. Koothumadams are found in various bhadrakali temples of Palakkad, Malappuram, and Thrissur districts of Kerala. It is strategically situated outside the main shrine so that audiences from different castes can witness the show.

How Kamba Ramayana becomes the spine of storytelling

Chola monarchs bore Rama’s name in their imperial titles, even perceiving parallels between their conquest and Rama’s when they erected icons of the epic hero to celebrate a victory over the Sinhala kings of Lanka. One temple inscription goes so far as to suggest the story of Rama as an origin myth for the Cholas, which was a solar dynasty like Rama’s. In Indian history, Rama stood as a paradigm of political power and a model of kingship, so a Chola king, as the puppeteers tell it, commissioned Kampan, and his rival, Ottakkuttan, to compose a “Ramayana in the southern tongue.”

Ram was traditionally depicted in Valmiki’s original writing as a man who resided in this world. It served as a witness to Rama’s life and sent a powerful message that helped establish Lord Raman as a person of integrity. On the other hand, Kamban Ramayan presents Raman as a man while elevating him to the status of God. Kamban emphasizes that Raman is a God in every instance, with varying strengths and weaknesses; the main intention of the text is to increase awareness of God – Raman, balancing the qualities of God and human nature. It is quite striking because nowhere in the epic does Kamban’s Raman mention that he is an incarnation of Lord Vishnu.

The Kamban Ramayan used for Tholpavakoothu shadow art has five books. The birth and marriage of Rama to Sita are described in the first book, Bala Kandam (the Birth Book). The Palace shenanigans and Rama’s banishment are recorded in the second book, Ayodhya Kandam (the Ayodhya Book). The third book, Aranya Kandam (the Forest Book), follows Rama, Laksmana, and Sita’s adventures with sages and demons after they leave Ayodhya and travel into the forest. The fourth and fifth books, Kishkindha Kandam and Sundara Kandam (the Kiskindha Book and the Beautiful Book) are filled with events that span from Sita’s kidnapping to the conflict with Ravana. The sixth and last book of Kampan is the Yuddha Kandam (War Book). Rama and Sita are reconciled, and they travel back to Ayodhya for Rama’s delayed coronation, which serves as both the Tholpavakoothu puppet play’s and Kampan’s text’s last scene.

The sacred arrow of Lord Rama is handed over to the head Puppeteer ‘the pulavar’ before this enactment. This arrow is carved out of Palmyra wood by an individual belonging to the Kurupa Community (Nair). The arrow (Ramasharam) and the black Ayapudava (the black lower cloth of the screen) are returned to the temple following the performance cycle there. All the performers share a portion of the white Ayapudava (cloth screen). To symbolize a successful outcome, betel leaves and nuts are chewed.

With time, this Indian shadow puppetry has grown and changed to reflect the shifting attitudes of the populace. From 1969, a condensed version of Ramayana began to be performed at additional venues outside temples. This hour-long presentation exclusively includes sections from the Ramayana that have major plot points and greater action. Additionally, this version is presented for audiences internationally and at events supported by the government. International exposure to various puppetry forms inspired the Tholpavakoothu artists to explore novel topics. This resulted in a new performance in 2007 based on Mahatma Gandhi’s life and hardships, and another in 2012 focused on Jesus Christ for Kerala’s substantial Christian community. Art imitates life.

References

- Sinha, Atul, 2020. Caste, Gender and Space in Tholpavakoothu Shadow Puppet Performances in Bhadrakali Temples of Kerala. Journal Of Uttarakhand Academy Of Administration, Nainital (JUAAN), pp.64-76.

- Nishanth, A., 2021. Tholpavakoothu: A Study On The Performing Art Of Shadow Puppetry In Kerala.

- Blackburn, S., 1996. Inside the Drama-House: Rama stories and shadow puppets in South India. Univ of California Press.

- Subramaniyan, Chandrika. (2021), ‘Valmiki and Kamban: The Ramayanam Differences’, ‘Shreymaya’. Available at: https://www.shremaya.org.au/board/post/valmiki-and-kamban-the-ramayanam-differences

- May 15, 2024

- 6 Min Read