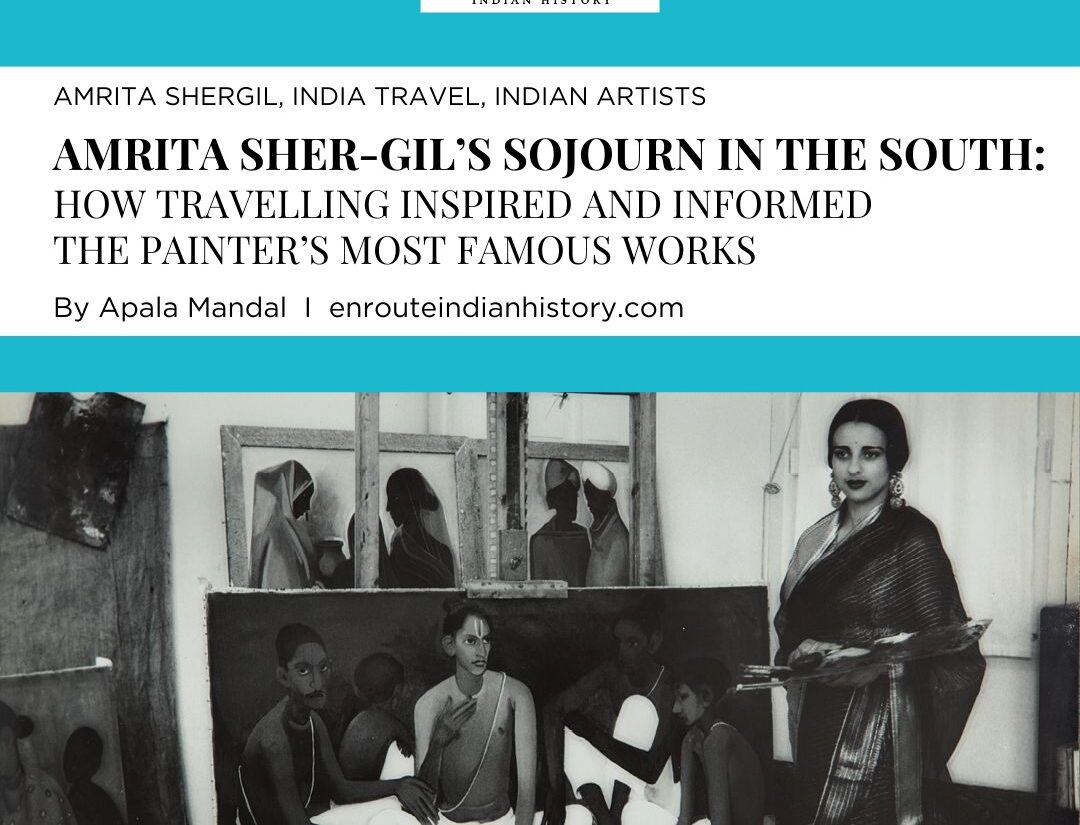

Amrita Sher-Gil’s Sojourn in the South: How Travelling Inspired and Informed the Painter’s Most Famous Works

- EIH User

- April 3, 2024

Over the years, many poets, writers and thinkers have pointed out the powerful relationship between travel and art inspiration. Perhaps none have done so as succinctly as Jonah Lehrer, who once said, “We travel because we need to, because distance and difference are the secret tonic of creativity.” For remarkable Indian and Hungarian artist Amrita Sher-Gil, travelling provided an invaluable opportunity to explore palettes, themes and art styles very distinct from the European art traditions she had been trained in at Paris and Florence. This article uses letters by Sher-Gil and the accounts of her biographers to explore how a tour of South India between 1936 and 1937 shaped the artist’s trajectory and helped her make some of the most renowned Indian paintings

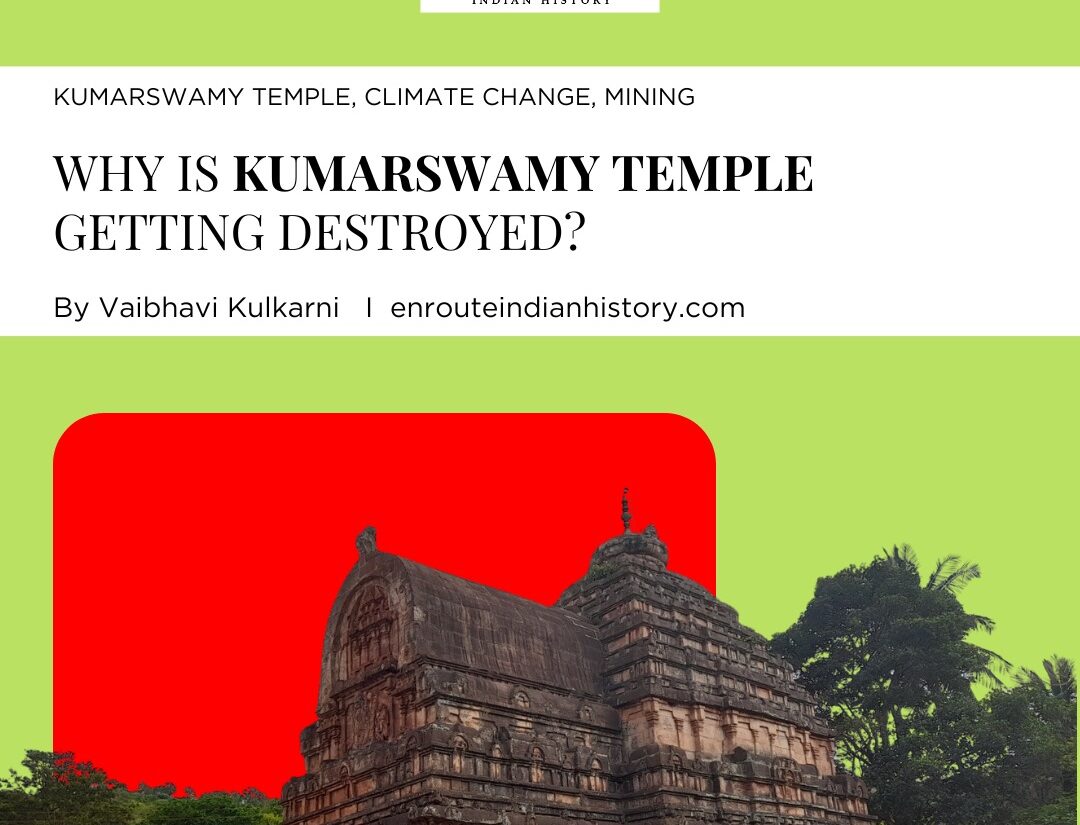

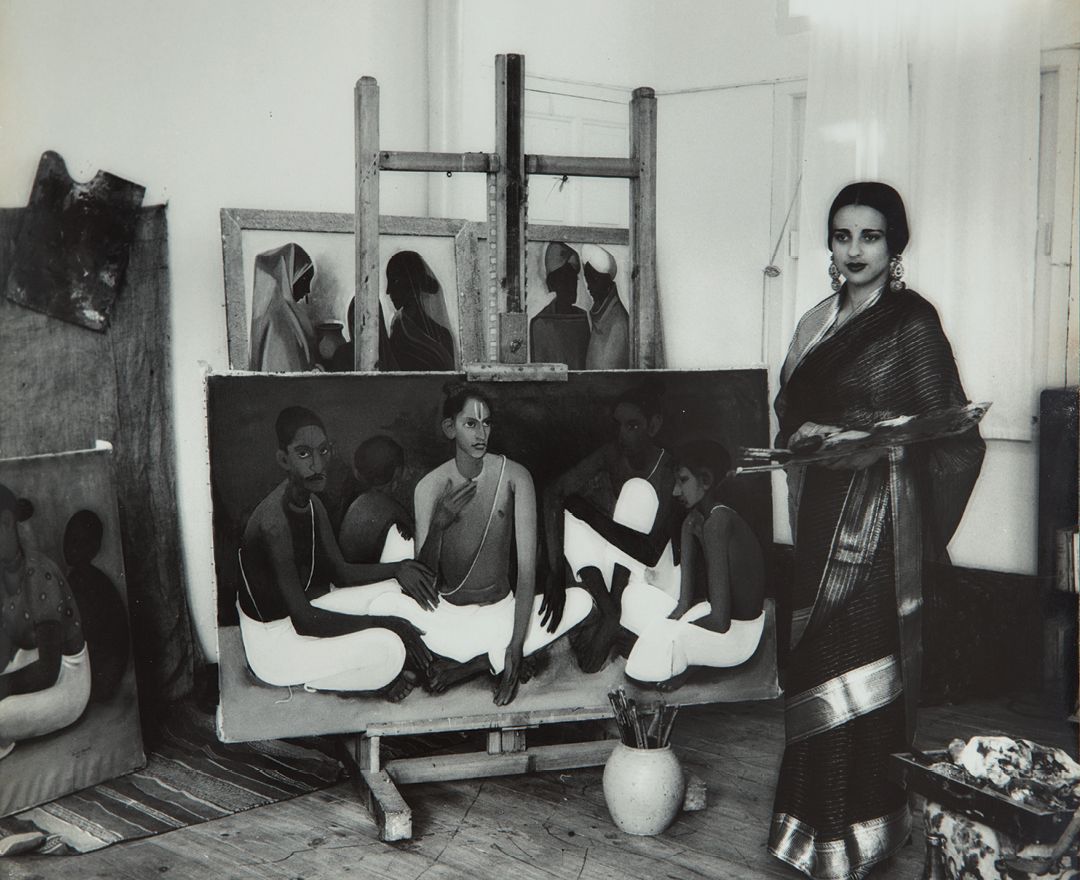

Figure (a): Amrita Sher-Gil (likely in her studio in Simla) in the late 1930s, painting ‘Brahmacharis’. Image Source: Delhi Art Gallery (DAG)

Figure (b): Amrita and her younger sister Indira, to whom she wrote letters throughout her travels.

Image Source: The Artisera Blog

Amrita Sher-Gil, a Masterclass in Fusion:

Sher-Gil’s powerful impact on Indian art puts her firmly in the league of stalwarts like Rabindranath Tagore and Jamini Ray. Her art is internationally acclaimed, and her sensitive portrayals of women and the poor render her works revolutionary across contexts. What truly sets her apart, though, is her ability to blend elements of Western and Indian art together, producing a quintessential style that quickly became her trademark. Many have dubbed her the Frida Kahlo of India based on this ability to merge techniques and traditions. Besides being contemporaries, Kahlo and Sher-Gil’s lives have many parallels that contributed to both artists’ creative journeys: travelling around the West but longing always for home was only one of these many commonalities (Soni 2019).

Her travels only sharpened a propensity for fusion, mixing and amalgamating that existed in Sher-Gil’s art from the very start. In a special issue of the Usha Journal of Art and Literature, Sher-Gil wrote, “My professor [in Europe] had often said that, judging by the richness of my colouring, I was not really in my element in the grey studios of the West, that my artistic personality would find its true atmosphere in the colour and light of the East.” (Sher-Gil 1942). She returned to India in 1934, and after meeting Karl Khandelvala—an art collector and critic who would become one of her strongest supporters—she set off to travel the country and reconnect with Indian art forms and styles. While she was known to have appreciated Mughal miniatures and the traditions of the Pahadi school of art, her art was fundamentally transformed by her travels in South India and her visits to the cave paintings of Ajanta.

Figure (c): Sher-Gil travelled to France for her early art education at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts. Image Source: Wikicommons

Figure (d): Sher-Gil also studied art at The Académie de la Grande Chaumière in Paris. Image Source: Courtney Traub for Paris Unlocked

The Tour of the South:

In the company of Barada Ukil (one of the three Ukil brothers who eventually set up the All India Fine Arts & Crafts Society), Amrita Sher-Gil spent several months travelling around South India. Her reflections and recollections of this period are preserved in the many letters she wrote to her parents, sister, friends and colleagues like Karl Khandalavala. Excerpts from these have been collected and brought together by Yashodhara Dalmia, in her acclaimed biography titled ‘Amrita Sher-Gil: A Life’ (2013).

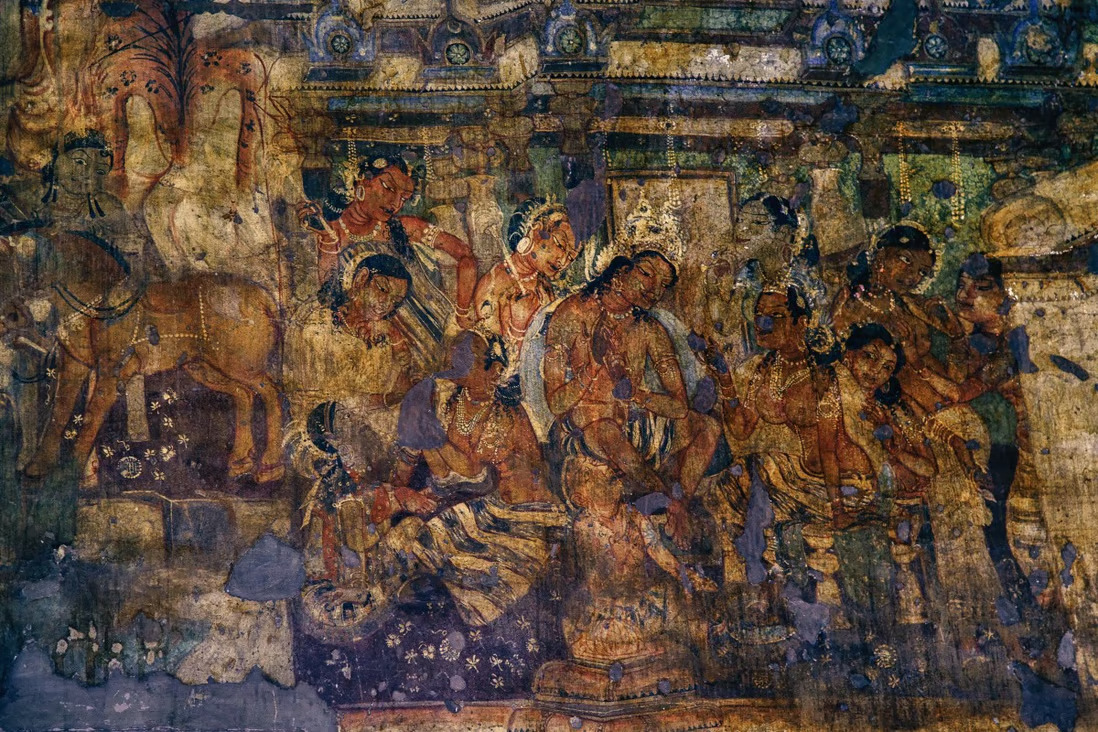

From Bombay, the first place Sher-Gil visited was Ajanta and Ellora, where according to Dalmia, she was “wonderstruck by the breathtaking sensuality and lyricism of the cave paintings and the temples” (2013). In a letter to her parents, she wrote, “Ajanta was wonderful. I have, for the first time since my return to India, learnt something, from somebody else’s work”. In her detailed reflections to Khandalavala, Sher-Gil critiques some aspects of the art at Ajanta (including the details of jewellery that she found “feebly painted”). However, she reiterates that the vast majority of the paintings at Ajanta are extraordinary. “I don’t think I have ever seen anything that can equal it”, she writes. While based near Ajanta, Sher-Gil made a number of small drawings that would influence her later paintings and become points of reference for much of her art in the future (Dalmia 2013).

Figures (e) and (f): These are some of the cave paintings Amrita Sher-Gil may have encountered on her travels to Ajanta, firmly shaping the trajectory of her art career.

Image Source for (e): John Griffiths (1877-78), MAP Academy

Image Source for (f): Emdadul Hoque Topu for Shutterstock

Travelling, while bringing us to new places and experiences, is also formative in its ability to introduce us to new people. In the next stop of her journey, Sher-Gil visited Hyderabad, where she met Sarojini Naidu, a woman she took an instant liking to. Sher-Gil was known to focus on the difficult predicament of Indian women in much of her artwork, and her interactions with Naidu—one of the most prominent women politicians of India—take up considerable space in her letters to her loved ones. Naidu continued to support Sher-Gil’s art career and sent a warm letter of condolence when the artist passed away at the age of 28.

Next, Sher-Gil visited Madurai, Rameshwaram and Trivandrum, where she felt that the paintings and frescos of Ajanta had come to life. She was moved by the “rich emerald green vegetation”, “the red ochre-coloured earth”, and the “extraordinarily beautiful” people, men, women and children. “I do not know how I will ever resign myself to living and painting in Shimla, or for that matter, anywhere in North India after seeing the South”, she lamented in a letter written to her sister Indira in early 1937. Nonetheless, after visiting and painting on the beaches of Cochin, Sher-Gil returned to Shimla. Her connection with and inspiration from her travels in the South remained constant, as she began the task of painting her most famous works.

Painting the Trilogy:

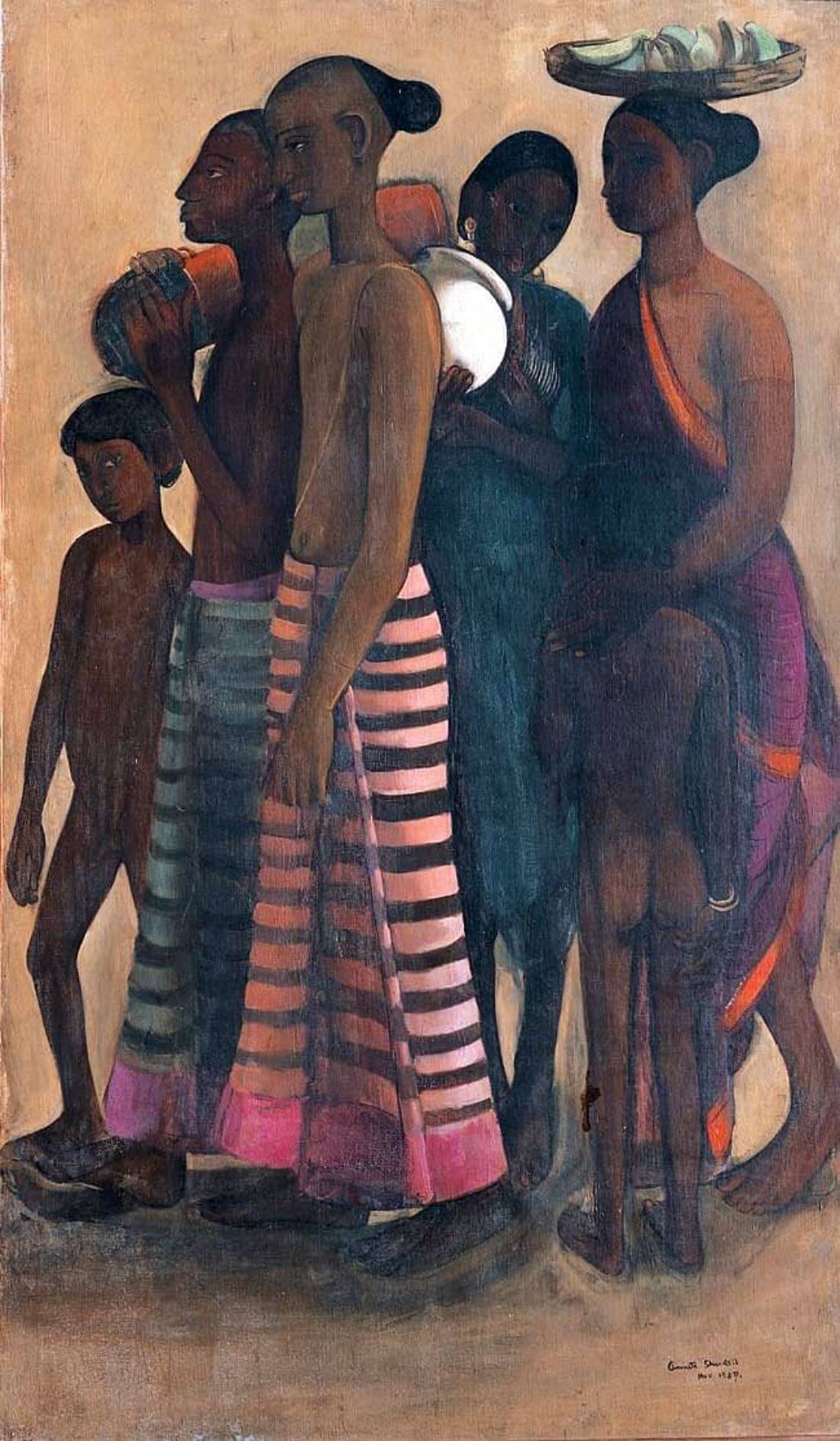

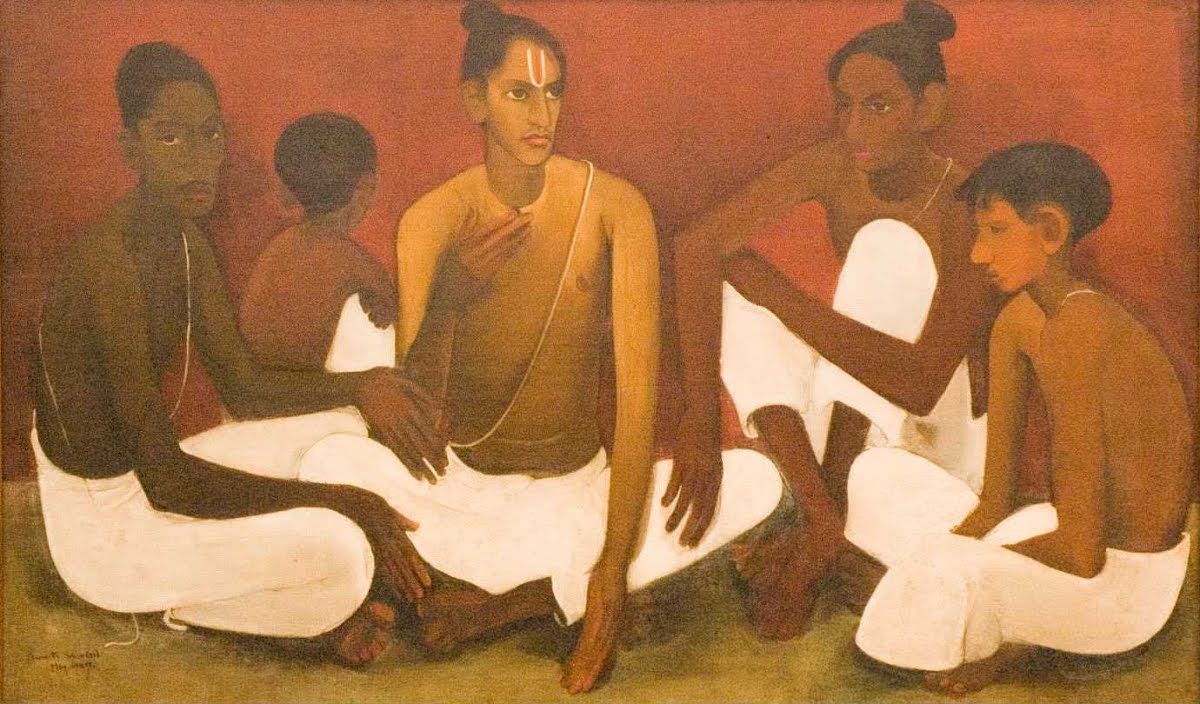

Sher-Gil’s South Indian Trilogy—including Bride’s Toilet, Brahmacharis and South Indian Villagers Going to Market—is perhaps her most well-known set of paintings. She painted them in Shimla, where sights, sounds and memories from her travels in South India began to surface and shape her art. According to Dalmia (2013), Sher-Gil painted with renewed enthusiasm and tried to capture the “colours, tonalities and expressive body movements” that she encountered in the South.

Figure (g): Bride’s Toilet (1937) by Amrita Sher-Gil, currently at the National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi (NGMA). Image Source: Wikicommons

Figure (h): South Indian Villagers going to Market (1937) by Amrita Sher-Gil, currently at the NGMA.

Image Source: Wikicommons

Of course, one way to tap back into our memories of travel is to surround ourselves with material reminders of where we went (tourist souvenirs, knickknacks, the food and culture of the places we visited). Sher-Gil used this strategy too—she needed to use live models in her paintings and therefore made her North Indian servants in Shimla dress in colourful clothes she had carried back from the South (Dalmia 2013). “I propose to dress the bleak hill types in the glowing colours of the south, to give them a little glamour and attraction. I am dying to get down to work. I am teeming with ideas”, she wrote to her sister.

And work she did. The Bride’s Toilet, Brahmacharis and South Indian Villagers Going to Market, all reflect her time in Ajanta and the South. A constant feature in her work is the blending of Indian and Western influences, which is evident in these pieces, especially in the reflective ambience she created in Bride’s Toilet. The figures and forms in the Trilogy paintings are simplified, and their poses are inspired deeply by what Sher-Gil saw at Ajanta. Notably, the paintings are permeated by a bold and fearless use of colour. Indeed, we can immediately see the rich hues of flaming red, deep green and burnt earthy brown that she was so impacted by during her travels. The clothes Sher-Gil’s characters wear are vibrant, but most significant is her choice to use almost blinding (but still varied) shades of white, similar to the colour of the dhotis, lungis and sarees she saw people wearing in the temple town of Madurai. We see this most explicitly, perhaps in Brahmacharis.

Figure (i): Brahmacharis (1937) by Amrita Sher-Gil, currently at the NGMA.

Image Source: Google Arts and Culture.

In South Indian Villagers Going to the Market, there is a striking sense of mobility. In the words of Dalmia (2013), the figures in the painting, with their “burnt sienna bodies and brilliant clothes”, seem to have “stepped down from the cave walls to the present, as they go about their day-to-day affairs”. This sentiment is echoed by others, including artist K.G. Subramanyam, who stated that in this final painting, “Amrita came closer to the appreciation of the special character of Ajanta paintings than most, its studied disposition of masses, its rich and mellow colour play. She also came nearer to seeing the sensuous humanism of Ajanta than many” (Subramanyam 1972). The Trilogy is a true and pointed illustration of how closely related art and travel are, and how each can strongly impact the other.

Amrita Sher-Gil, an Interpreter of Indian Life:

One final connection between art and travelling that this essay will explore is the opportunities that travelling provides to deepen experiences and offer authenticity. Critics of Sher-Gil often pointed out her foreign training to suggest that she could not truly be an Indian artist. While Sher-Gil retaliated by saying that she saw her vocation as “an interpreter of Indian life”, Geeta Kapur is quick to note the limitations of this claim. Kapur suggests that in early work, Sher-Gil was painting the poor and wretched of India from a position of pure aesthetics. This choice, compounded by several layers of class privilege that alienated Sher-Gil from the poor she painted, resulted in her early work offering only superficial images (Kapur 1972).

By travelling around the country at length, Amrita Sher-Gil was able to learn more about the conditions of the subjects she painted, and the reality of their lives. This knowledge became interwoven into her painting practices, culminating in richer, more rooted, and more profound paintings in the later part of her career. The South Indian Trilogy is a great example of this. Geeta Kapur, focussing specifically on Brahmacharis, suggests that the success of the painting comes from Sher-Gil’s developed familiarity with the Indian environment, which allows the artist to “impart a greater authenticity” to the paintings she produces. Not only is that authenticity present in the scenery, colours and environment of the painting (consider the earthy tones, inspired by the actual colour of the earth Sher-Gil saw in South India), but also in the characters. In Brahmacharis, each character is subtly differentiated from each other, but the commonalities in dress and habit indicate a shared social context. According to Kapur, this allows for a “remarkable balance” (1972), between a realism that makes these characters authentic and believable and a stylisation that fills the painting with rhythm, design and unity.

With these paintings propelling her reputation and reverence, Sher-Gil rose to great heights in Indian art, until her career was tragically cut short. Like all great artists, her oeuvre is a product of several influences. Nonetheless, the role of travelling in inspiring, shaping and sharpening her art is undeniable, and the art world is all the richer for her decision to explore her country.

References:

Dalmia, Y. (2013). Amrita Sher-Gil: A Life. Penguin Random House India.

Kapur, G. (1972). The Evolution of Content in Amrita Sher-Gil’s Paintings. In: V. Sundaram, G. Kapur, G.M. Sheikh and K.G. Subramanyam, eds., Amrita Sher-Gil: Essays. New Delhi: Marg Publications, pp.39–54.

Sher-Gil, A. (1942). Evolution of My Art. Usha Journal of Art and Literature: Special Edition on Amrita, 3(2), p.99.

Soni, M. (2019). Frida Kahlo and Amrita Sher-Gil: Soul Sisters. India Currents. Available at: https://indiacurrents.com/frida-kahlo-and-amrita-sher-gil-soul-sisters/

Subramanyam, K.G. (1972). Amrita Sher-Gil and the East-West Dilemma. In: V. Sundaram, G. Kapur, G.M. Sheikh and K.G. Subramanyam, eds., Amrita Sher-Gil: Essays. New Delhi: Marg Publications, pp.63–73.

- May 15, 2024

- 6 Min Read