Building Blocks of History: Tracing India’s Brick Evolution

- enrouteI

- August 3, 2023

Brick is the construction material we’ve all seen. As it turns out, bricks are literally the building blocks of history. The humble brick stands as an enduring testament to the rise and fall of civilizations, narrating tales of power. Bricks serve as silent witnesses, speaking eloquently of the societies they built. This article attempts to trace bricks throughout Indian history, exploring their significance from the Indus Valley Civilization to contemporary India.

The Indus civilization extended across the plains of Punjab, Sindh, Baluchistan, the Gujarat coast, encompassing an area of about 1 million km2 at its peak, comprising of thousands of individual sites. Although usually referred to as the Indus Valley Civilization, the Indus Valley was only one among the many river valleys the civilization spawned around. The Daksht Valley of the Makran coast in the West, the Ganga Yamuna Doab in the East, the Tapti Vally in the South, and the Oxus in the North Afghanistan straddled the settlements of this ancient civilization. Cities that have been recognized today include Harappa and Mohenjodaro, both of which contained about 40,000 residents each at their peak. The total population in the mature phase (2500-1900 BCE) is estimated to be about a few million people.

The Indus Civilization reveals the use of bricks since around 7000 BCE. This is when the earliest mud bricks have been found at the site of Mehrgarh. The settlements of Amri and Kotdiji are also made from mud bricks. Mud bricks are bricks made with clay and water that are sundried. The hotter the sun, the stronger the brick. In contrast, baked bricks were heated in ovens called kilns that would strengthen the bricks. Baked bricks occurred for the first time at Jalilpur approximately in 2800 BCE. Most large cities of the civilization, such as Harappa, Mohenjodaro, Kot Diji, Ganweriwala, Rakhigarhi, and Lothal have been found to utilize both mud and baked bricks. Only one large Harappan city, Dholavira, is built entirely from mud bricks. The bricks followed a typical “Indus proportion”, or a standard ratio of 4:2:1 (length to width to height). The adherence to this ratio was ensured by the use of standardized moulds.

A photo of the Indus Valley Civilization’s large settlement, Mohenjo-Daro, in what is now Sindh province, Pakistan. The settlement was abandoned in the 19th century B.C. (Image credit: Pavel Gospodinov via Getty Images) via Live Science

Baked bricks saw widespread use largely during the Mature Harappan phase. After 1900 BCE, large cities were abandoned and baked brick manufacturing was discontinued. Thus, the period of baked brick usage coincides with heightened urbanism, large cities as opposed to village settlements. Other technologies such as writing, shell ornaments, weights, and seals also flourished in this highly urbanized period. A close relationship between building materials and cities at large is thus evident. This relationship also translated into the social domain. While mud bricks harden fast and have better thermal insulation, they are not as resistant to water. In Harappan cities, water-resistant construction material was required, as is evident from the widely known baths, drainage systems, and flood protection structures. The production of baked bricks, however, despite this important benefit, is much costlier. They needed to be heated to very high temperatures to be strong enough. This technology thus required skilled labor and resources. These standards are preserved in craftsmen’s traditions and social norms. A high degree of knowledge was needed to figure out the proportions of mixing silts and water and find the right temperature and roasting time to produce bricks of adequate strength. The fall in baked brick usage could be indicative of a lack of skilled craftsmen. Whether they migrated or stopped producing due to a change in social norms remains unknown.

A significant portion of the archaeological remains from the Indus Civilization comprises bricks. They hint towards insights into the correlation between technology, construction materials, and societal development during the peak of the Indus Civilization. Jumping far ahead in time, lakhauri bricks and nanakshashi bricks were used as construction material in impressive structures of Indian history constructed roughly during the 16th to 18th centuries. Hundreds of centuries apart, these bricks also reflect the evolving architectural practices and craftsmanship over time. This construction material continued to contribute to the grandeur and durability of architectural marvels across the Indian subcontinent, and that different rulers, in different areas of the subcontinent utilized unique bricks might also highlight the power of bricks in projecting distinct royal authority.

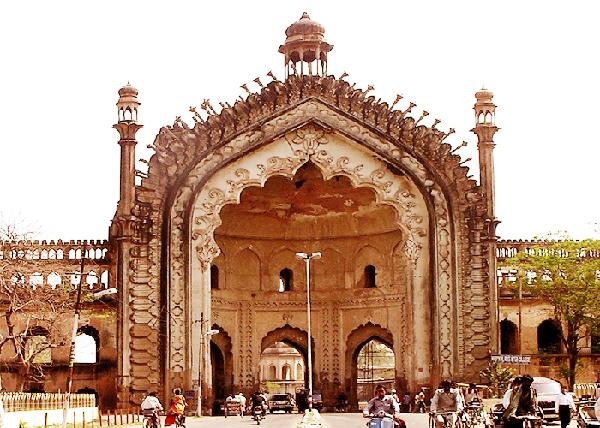

The lakhauri bricks are characterized by a flat, rectangular shape, with typical dimensions of 100 mm x 150 mm x 20 mm or 100 mm x 150 mm x 50 mm. These bricks are an essential element in the construction of the architectural marvels of this era. Among the most notable buildings using this brick are the Bada Imambara, and the Rumi Darwaza in Lucknow.

Bada Imambara at Lucknow. Source: Tutorialspoint

Another significant historical structure, Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s palace, was constructed using Nanakshahi bricks, distinctive to the Punjab region. Nanakshahi bricks are known for their small, thin, and multi-hued appearance, exhibiting strength and resistance against frost and adverse weather conditions. These bricks are created through a process of burning and powdering, resulting in their unique characteristics. The average size of Nanakshahi clay bricks is approximately 18.3 cm in length, 9.4 cm in width, and 2.7 cm in height, with a weight of about 1.28 kg per brick.

While bricks could also be signifiers of royalty, for the common people, bricks also denoted class and caste status. Anil Laul writes, “The lower the caste, the slimmer and smaller the brick, the higher the caste, the bigger the brick”. People from upper castes could afford the resources needed to strengthen bricks, such as blending clays, fuel, and transport, whereas those who couldn’t had to rely on slimmer bricks that used less fuel in their making.

Thus, from impressive historical monuments to social markers, bricks played a multifaceted role in shaping India’s architectural landscape and societal structure. The legacy of these remarkable construction materials continues to resonate today. With an annual production of around 250-300 billion bricks, India is the world’s second-largest producer of bricks in the world, generating seasonal employment for 10 million people. The demand for bricks is expected to increase multifold due to the burgeoning sectors of transportation and construction. Today’s bricks, at 190 mm x 90 mm x 90 mm, weighing in at about 3 kg, look very different from the bricks of the bygone eras. Newer construction materials and technologies have also emerged, with fired clay bricks now being the norm. This industry is also the largest consumer of coal in the country.

Exposed Lakhori bricks used to build a kos minar or milestone. Picture Source : Wikipedia Commons

As we look upon the magnificent structures standing strong, from grand historical monuments to contemporary skyscrapers, we must acknowledge the unyielding spirit of the brick. The humble brick, more than a construction material, can also speak to power relations and societal structures. These unassuming rectangular blocks have played a foundational role in Indian history and shaping societies.

Bibliography

Bhushan, Chandra. “No Bricks in the Wall”. Down to Earth (2019). https://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/air/no-bricks-in-the-wall-64510

Bureau of Energy Efficiency. “Market Transformation towards Energy Efficiency in Brick Sector” (2019). https://beeindia.gov.in/sites/default/files/Brick%20Sector%20Market%20Transformation%20Blueprint_BEE%281%29.pdf

Kamyotra, J.S. “Brick Kilns in India”. (n.d.). https://cdn.cseindia.org/docs/aad2015/11.03.2015%20Brick%20Presentation.pdf

Khan, Aurangzeb, and Carsten Lemmen. “Bricks and urbanism in the Indus Valley rise and decline.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1303.1426 (2013).

Laul, Anil. “Urban Red Herrings” Zingy Homes (2015).https://www.zingyhomes.com/latest-trends/human-settlement-planning-design-sustainability/

Malhotra, Mona. “A study of conservation interventions at Ram Bagh, the summer retreat of Maharaja Ranjit Singh at Amritsar.” Creative Space 1, no. 1 (2013): 39-61.

Rai, Durgesh C., and S. Dhanapal. “Bricks and mortars in Lucknow monuments of c. 17–18 century.” Current science (2013): 238-244.

Singh, Guljit, Anshu Tomar, and Varinder Singh Kanwar. “Physical, mechanical and crystallographic properties of clay bricks and mortars of the sixteenth–nineteenth century monuments of East Punjab.” Journal of Building Pathology and Rehabilitation 7, no. 1 (2022): 82.