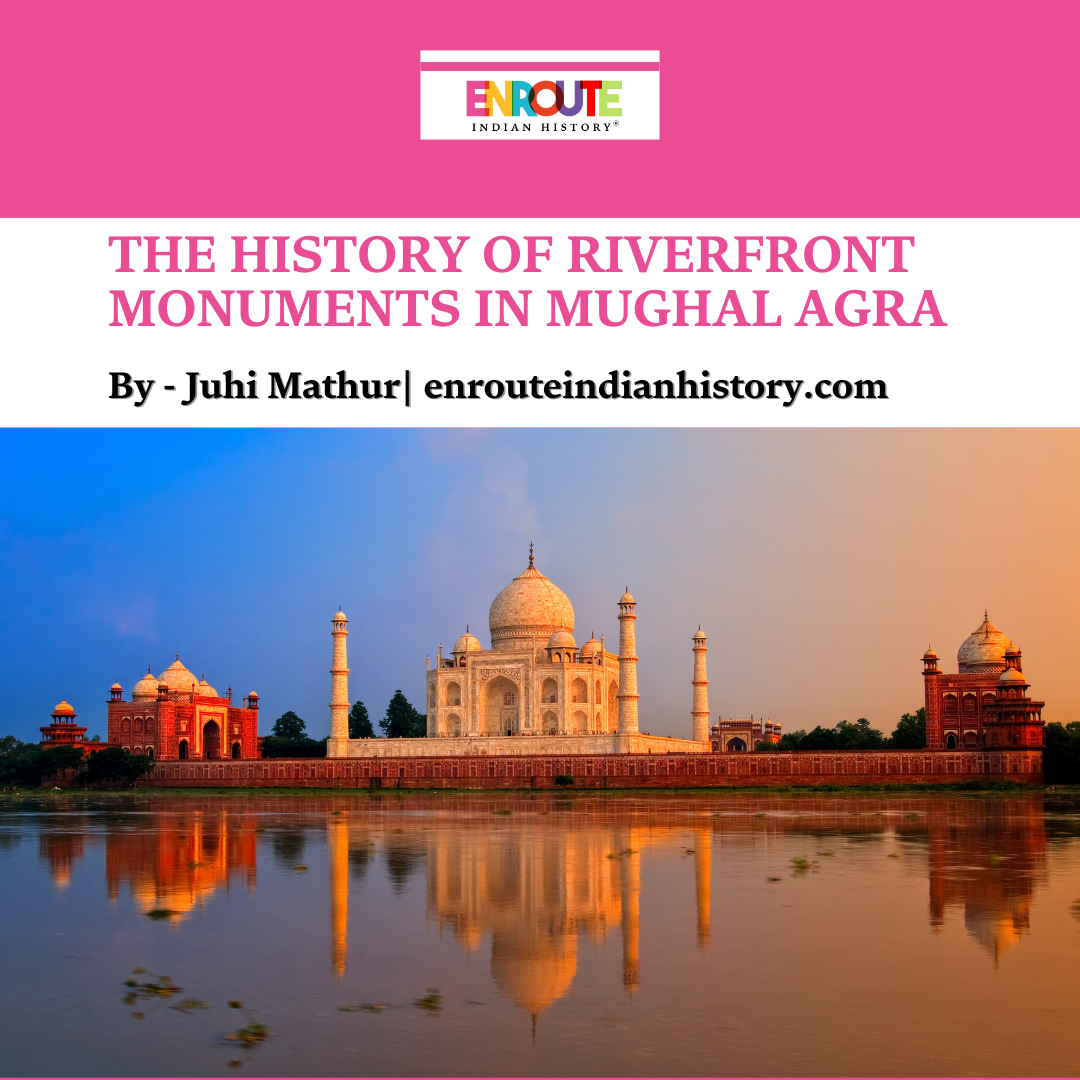

Chronicling the History of Riverfront Monuments in Mughal Agra

- iamanoushkajain

- June 14, 2025

By Juhi Mathur

The city of Agra is akin to an old historic text containing letters from different individuals who defined the meaning of Agra itself in their respective ways, some writing poetry about love and some writing odes to the beauty of its land. In simpler terms, Agra is a historic city with imprints of different cultures as a result of constantly shifting sovereign power. In the Mughal empire, Agra’s identity as a riverside city became an integral part of town planning initiatives, thriving as the main capital when Babur set his base in Hindustan in 1526 CE. Originally, it has been estimated that a total of 44 gardens (both riverfront and inland) were present in the city, many-18th century was eroded or destroyed by invaders after the weakening of the Mughal empire post-18th century.

River complexes and their cultural significance

River complexes and their cultural significance

Ebba Koch has studied the heritage of Mughal Agra and the history of Islamic architecture in the city through various methodologies and pointed out that the riverfront gardens and carefully composed structures were an inherent part of the town planning and landscaping, claiming that there at least forty-four such riverfront gardens (baghs). Both the banks of river Yamuna (also known as Jamuna or Jamna) were lined with palatial houses, imperial gardens, tombs, and mansions, the right bank had houses belonging to princes and mansabdars (an individual holding an important rank in the Mughal court) whilst the left bank was usually reserved for imperial gardens. A very important aspect of riverside land was that it could not be bought by anyone, and they were offered only to the members of the nobility and high ranks by the emperor. This facet of unattainability made the riverside sites a symbol of prestige and power, becoming an architectural remnant of a family’s lineage and history. However, these lands could be reclaimed after the death of the designated noble, to prevent this reclamation, nobles ensured to build a tomb at the riverside gardens, converting them into tomb gardens and preserving their legacy. After Shah Jahan shifted his capital to Delhi in 1648, the palaces and garden tombs in Agra became significantly less important and their historiography became more of an obscure part of the past

Riverside Gardens in the Mughal Empire

Ebba Koch has explained that the construction of riverfront gardens especially during Babur’s reign was a symbol of power more, citing James Wescoat, who argued that Babur built gardens in citadels and fortresses that belonged to the pre-Mughal era. This showcased opposition towards his rivals, and these structures became “emblems of territorial control”, CatherineAsher noted that Babur’s choice to build gardens was also to establish a new aesthetic that represented the stylistic characteristics of Mughal reign. He built most of his garden complexes on the opposite bank of river Jamuna (modern-day Yamuna) directly opposite the fort of the last Lodi Sultan.

Originally a resident of Samarkand, and later on with a sovereign in Kabul, Babur found the balmy city of Agra a complete departure from the pleasant winters of Kabul and Central Asia, and it is also deciphered from his autobiography Baburnama that he found it hard to acclimate to the weather and surroundings of northern Indian plains. Nostalgia and Babur’s love for botany and horticulture led him to build various riverside garden complexes on the banks of Yamuna and around the city, notably – Bagh-i-Dahra, Bagh-i-Hasht Bihisht, Bagh-i-Zar-Afshan (now known as Ram Bagh), and Mehtab Bagh. He embedded the construction of these gardens with charbagh style, a Persian style of architecture where a square or rectangular garden is divided into four sections flanked by pathways (khiyabans) and water fountains. Ebba Koch has pointed out that before even the construction of these gardens, Babur issued a construction of a stepwell complex to facilitate the supply of water to gardens inside the forts. These gardens became an integral part of the Mughal culture and aided in transforming the landscape of the city, as many of these gardens were built around the periphery of the city, therefore they added to the luxurious aesthetics of the city and also served as pleasure gardens for the nobility. Beyond that these gardens could be orchards, gul,istans, or they could be for funerary purposes. It has been noted that during Shah Jahan’s reign the relationship between the garden complex and the tomb became more pronounced as seen in the layout of the Taj Mahal.

During Akbar’s reign, the Mughal city of Agra thrived and developed as a riverbank city becoming the official imperial headquarters for the royal family. Both the sides of Yamuna River were flanked by various gardens and even Akbar’s fort was constructed under a garden scheme. One of the elaborate structures in the fort is Jahangiri Mahal, which is a riverside courtyard which was built on the southern end of the residential axis facing the Jamuna River on the east. It is noticeable that though the Agra Fort is devoid of any gardens at present, the Jahangiri Mahal had an elaborate garden as well as elements of water architecture. The palace used to have a garden below jharokha-i-darshan, and Ebba Koch points out that English merchant William Finch would describe this garden as a curious garden, from where Jahangir boarded a boat to travel to another garden on the other side of the river. This showcased that gardens were prominently built outside the forts as part of the riverfront architecture.

Jahangir’s reign and riverside monuments in Agra

Apart from the Jahangiri Mahal garden in Agra fort, the two surviving riverfront architectural remnants are Aram Bagh which was built by Babur in 1528 CE and followed a pattern of Hash Bihisht rather than Char Bagh and it was reworked by Jahangir’s wife Nur Jahan as Bagh-i-nur-Afshan (Light-Scattering Garden) in 1621, the gardens show Nur Jahan’s expertise in garden and beautification of the space, and it was captured in the visual vocabulary of Mughal muraqqas (albums).

Another garden complex that lies on the eastern bank of Yamuna, and between Aram Bagh and Chini ka Rauza, it is known as Zahara Bagh (Bagh-i-Jahanara) and was laid out by Mumtaz Mahal around the late 1620s. The identification of this tomb was carried out by Ebba Koch who cited the Map of Agra found in the collection of Sawai Man Singh II Museum in Jaipur, and a thorough research of the architecture placed the garden complex in the period of the early seventeenth century. Ebba Koch identified the garden complex belonging to Shah Jahan’s eldest daughter Jahanara, through her research of the work of Abu Talib Kalim, a poet in Shah Jahan’s court.

“Among the eulogies which Kalim wrote for Shahjahan, we find a lengthy mathnawi on Agra. Already its title contains a reference to the Bagh-i-Jahanara and a major portion of the poem is dedicated to the praise of this garden“.

The verse functions as an ode to the marvels of the imperial Mughal gardens while serving as a testimonial to the architectural details of the space.

Both the complexes (Aram Bagh and Bagh-i-Jahanara) share a similarity in their layouts which became a defining factor for the future Mughal palace architecture. The main building was in the centre of the garden as it previously was in the Charbagh plan, instead, the main complex was shifted to the terrace region, lining the river bank. The terrace structure would be flanked by corner towers of the garden’s enclosure wall. Ebba Koch has pointed out two advantages due to this layout change – a respite from the semi-arid weather as the running water made the climatic conditions favourable and the complex provided a solidified front to an observer who saw the garden from a boat or the other side of the river bank.

The tomb commissioned by Nur Jahan

One of the architectural gems from Agra, the tomb of Itimaud-ul-Daulah was one of the earlier examples of marble tombs and mausoleums, it is also known as a precursor of the Taj Mahal in terms of the pietra dura work as well as the usage of white marble. It is a mausoleum dedicated to Mirza Giyath Begh, Lord of treasure and vizier to Jahangir, who was given the title of Itimad-ud-Daulah. Situated on the left bank of Yamuna, at a 1km distance from Chini ka Rauza (a funerary tomb of scholar and poet Shirazi who was the grand vizier in Shah Jahan’s court), the tomb was built by Begh’s daughter Nur Jahan, who was given this land by her husband Emperor Jahangir, the construction of tomb completed in 1628, seven years after Begh’s death, the tomb also has the grave of Nur Jahan’s mother. This funerary complex reflects the political power of Nur Jahan and it is an example of Mughal architecture which was commissioned by a woman. This structure held significance for Mumtaz Mahal, as Mirza Giyath Begh was her uncle and this space itself held a lot of importance as a symbol of power for the noble houses by association with the royal family.

Riverside architecture during Shah Jahan’s reign

During Shah Jahan’s reign, the canonical format of riverfront monuments and gardens developed further and employed advanced technology to create riverside structures, most notably seen in the mausoleum complex of the Taj Mahal. Considered to be one of the greatest architectural marvels from pre-modern India, the Taj Mahal is a testament to sublime beauty and technical prowess in the land of world architecture and it was constructed keeping that in mind, Ebba Koch points out that the words of Shah Jahan’s early historian Muhammad Amin Qazwini, writing in the 1630s:

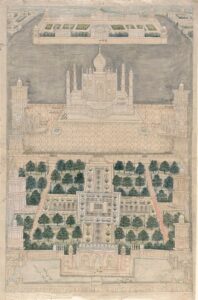

The layout of the Taj Mahal follows a typical layout of the riverside tombs and gardens of Mughal Agra, with a char bagh garden which leads to the main tomb that stands on the river bank, constructed on a raised terrace.

Koch has pointed out that, unlike the waterfalls and mountain springs in Central Asia, where the monument was built against a slow-moving river, water was used to irrigate the vast garden complex including the ponds and fountains that are festooned in the garden. Even the char bagh plan is a result of the Indo-Gangetic plains, as it is placed on the inward or terrestrial side of the terrace while the domed mausoleum presents an exquisite front when viewed from a boat in the river or across from the opposite bank. Henceforth, the design also kept the aesthetics of the space in mind.

Another important aspect of the Taj Mahal is the Khan-i-Alam Bagh on the right bank of Yamuna between the Taj Mahal and the tomb of Sayyid Jalal Bukhari. The bagh belonged to an important noble, Khan Alam, whose name was Mirza Barkhurdar, he belonged to Jahangir’s court and was an important figure in several political endeavours. He was the official Ambassador to Iran and was sent to Safavid Persia to negotiate peace with Shah Abbas and maintain diplomatic relations after the conflict in Kandahar, quite interestingly Khan Alam’s presence has been included in the Mughal visual narratives from Jahangir’s reign. The garden also has Khan-i-alam’s mansion and tomb along with his family members, thus converting this space into a funerary complex. At present, the Bagh has been converted into a nursery which is maintained by ASI, and it is known for bearing the old structures of hydraulics that were used to irrigate the gardens of the Taj Mahal.

Each tomb and mausoleum that has been explored thus far in this article stands as a testament to the technological advancements that defined the Golden Age of the Mughal era, each of these tombs and gardens provides us with an aesthetic genealogy that helps us to configure the traditions of art and culture amongst the nobility. They have become an imprint of the past, providing opportunities for various scholars and researchers to understand humanity’s past, thus making them part of tangible history, which is under the protection of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). The restoration of Mehtab Bagh that began in the 1990s by ASI in collaboration with the World Monument Fund (WMF) helped to revive the beauty of this mid-sixteenth-century garden that was built by Babur. This project showcased the value of research in Mughal history, but more importantly also helped the scholars to recognise the eco-history of the period, by reviving the garden through planting the flowers and trees that belonged to the Mughal period. Similarly, we can see how the position of these monuments endangers their existence in the absence of awareness of their historical context as seen with the now-lost Bagh-i-Jahanara, which was already struggling against the currents of the river, crumbled and collapsed under the weight of negligence and irreversible damage caused by torrential rains in the region.

The analysis of the river embankments in Agra and the remaining monuments that are festooned in and around the city showcase the nuances of town planning that were practised by the Mughal empire, as they tried to present a city with a fortified front and furthering the aesthetics that signified their power and wealth. We find the elements of romanticism at the core of many riverside palaces with the presence of jharokhas and gardens that found their place in the eulogies of poets and artists playing on the sensorial experiential nature of water in culture. A city that shone under the moonlight when smells of gulabs permeated the pavilions of char bagh while the white marble of the tombs shone brightly. Delving beyond the concepts of paradise and garden in Persian literature, the architectural motifs tell fantastical stories of corporeal human beings.

Bibliography:

1. “Tomb of I’timād-ud-Daulah.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tomb_of_I%27tim%C4%81d-ud-Daulah.

2. Gommans, Jos. “The Agra Scroll: Agra in the Early 19th Century.” Asian and African Studies Blog, British Library, 18 Jan. 2018, https://blogs.bl.uk/asian-and-african/2018/01/the-agra-scroll-agra-in-the-early-19th-century.html.

3. “I’timad-ud-Daulah’s Tomb.” Archnet, https://www.archnet.org/sites/1557.

4. Menin, Sarah, et al. “Re-envisioning Mughal Riverfront Gardens in Agra: Conservation Approaches.” World Monuments Fund, 6 Apr. 2017, https://www.wmf.org/blog/re-envisioning-mughal-riverfront-gardens-agra-conservation-approaches.

5. Mutsuddi, Ipsita. “Exploring the Jahangir Mahal’s Red Fort, Agra.” Medium, 9 July 2021, https://medium.com/@i_mutsuddi/exploring-the-jahangir-mahals-red-fort-agra-177aceec6f1d.

6. “Mehtab Bagh – The Moonlit Garden in Agra.” Asia Grace Circle, https://asiagracircle.in/mehtab-bagh-otther.html.

7.”Itmad-Ud-DaulaTomb.” Asia Grace Circle, https://asiagracircle.in/itmad-ud-daula-tomb.html.

8. “Mehtab Bagh.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mehtab_Bagh.

9. Khan, Zafar Aafaq. “UP Authorities Fail to Protect Remaining Parts of Mughal-Era Jahanara Bagh in Agra.” Clarion India, 12 Oct. 2021, https://clarionindia.net/up-authotities-fail-to-protect-remaining-parts-of-mughal-era-jahanara-bagh-in-agra/?amp=1.

10. Banerjee, Tathagata. “Lost Garden of Jahanara.” Deccan Herald, 12 Aug. 2012, https://www.deccanherald.com/features/lost-garden-jahanara-2316762.

11. “Restored Mughal Gardens Bloom Along Agra’s Riverfront.” Smithsonian Magazine, Smithsonian Institution, 3 Apr. 2019, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/restored-mugal-gardens-bloom-along-agras-riverfront-180971258/.

12. Koch, Ebba. “The Taj Mahal: Architecture, Symbolism, and Urban Significance.” Muqarnas, vol. 22, 2005, pp. 128–49. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25482427. Accessed 11 Nov. 2024.

13. Akhtar, Salim Javed. “MAHTAB BAGH: AN IMPERIAL MUGHAL GARDEN AT AGRA.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, vol. 69, 2008, pp. 1083–90. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44147270. Accessed 11 Nov. 2024.

14. Koch, Ebba. “Mughal Palace Gardens from Babur to Shah Jahan (1526-1648).” Muqarnas, vol. 14, 1997, pp. 143–65. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1523242. Accessed 11 Nov. 2024.