Eid al-fitr, a significant celebration marking the end of Ramazan, held a prominent position within the lavish courts of the Mughal Empire. Concluding the Islamic holy month of Ramazan, Eid al-fitr was a period of splendor, intense religious devotion, and collective jubilation within the Mughal Court. Nevertheless, the course of Eid al-fitr in Mughal history was far from uniform, as it mirrored the evolving notions of Mughal power and the varying policies pursued by different emperors. Throughout the reigns of various Mughal emperors, the celebration took on different forms, reflecting the distinct attributes of each ruler’s time in power. Even with these variations, Eid al-fitr remained a significant celebration until the very end of the Mughal dynasty.

(Illustration of the east gate of Jama Masjid in 1795 Image via Wikimedia Commons)

From Ferghana to Hindustan: Tumultuous Years

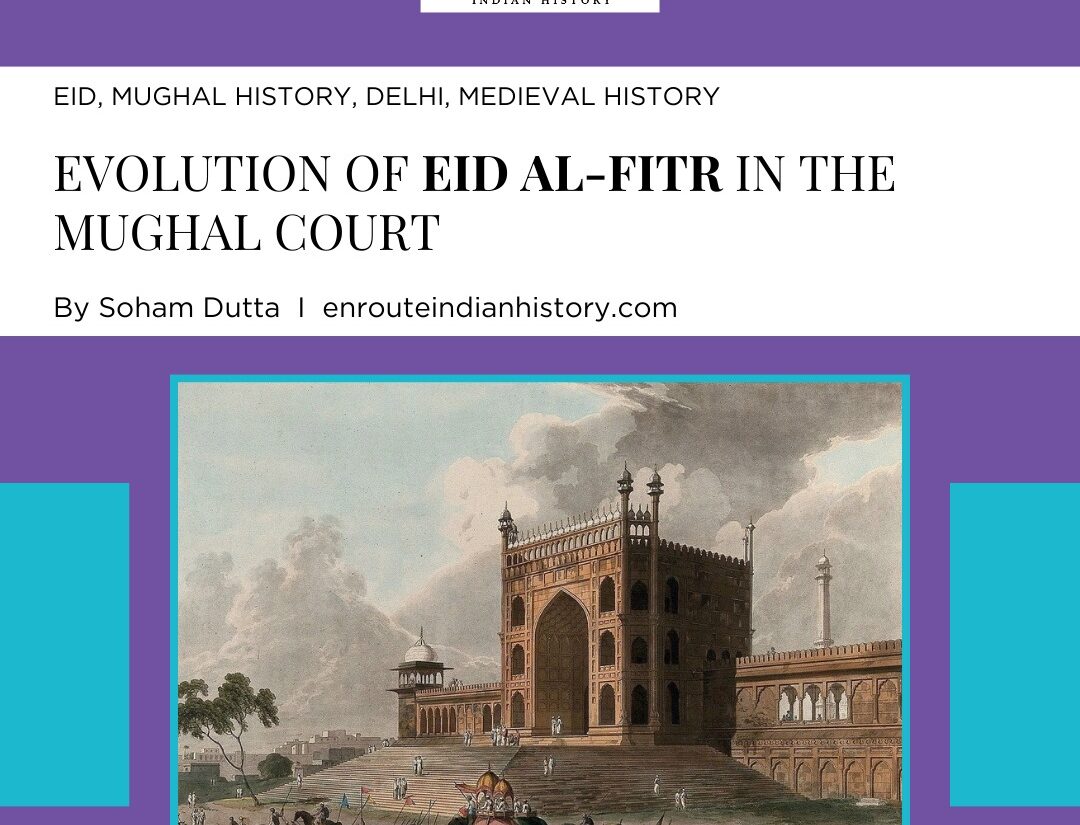

(Babur greets courtiers at the Id festival, via British Library,2012)

In his early years, Babur faced a relentless struggle to establish his kingdom after being forced out of Samarkand by the Uzbeks. For most of his life, he was deeply involved in battles and conflicts, leaving little room for lavish celebrations or the formalities that his successors would later adopt. Babur’s main emphasis was on military conquests, rather than engaging in lavish celebrations and elaborate court rituals. In his memoir, Baburnama, Babur himself recounts a fascinating detail about his annual Ramazan feast. He reveals that for over a decade, he made a deliberate choice to celebrate this important occasion in different locations each year due to military considerations. This practice of not keeping the feast in the same place for two consecutive years showcases Babur’s non-sedentary lifestyle and his constantly moving convoy.It was only in 1526 CE, after establishing their presence in northern India, Babur began to observe Ramazan and Eid al-fitr in a manner befitting their royal status. During the month of Ramazan, he dedicated his time to performing ablutions and engaging in tarawih prayers(adopting the 20 different postures of prayer). This spiritual practice took place in the serene garden, reminiscent of a heavenly paradise. In the garden of victory in Sikri, a stone platform was constructed on the northeastern side where feast tents were elegantly arranged. Nevertheless, he maintained the custom of not observing the sacred month of Ramazan in the same location for two consecutive years. In 1526 CE, he chose to celebrate in Agra, and in 1527 CE, he opted for Sikri. Emperor Humayun, his successor, faced a similar fate when he was exiled to Safavid Iran after being defeated by Sher Shah Suri.

During the latter half of the 16th century CE, the Mughal Empire, under the rule of Emperor Akbar, experienced a period of consolidation. It was during this time that new court etiquette and traditions were established. These changes paved the way for the formalization of various rituals and customs that were observed during imperial events and festivals including Eid al-fitr (Richards,1993).

Jashn-e-Eid: Heyday of Celebration

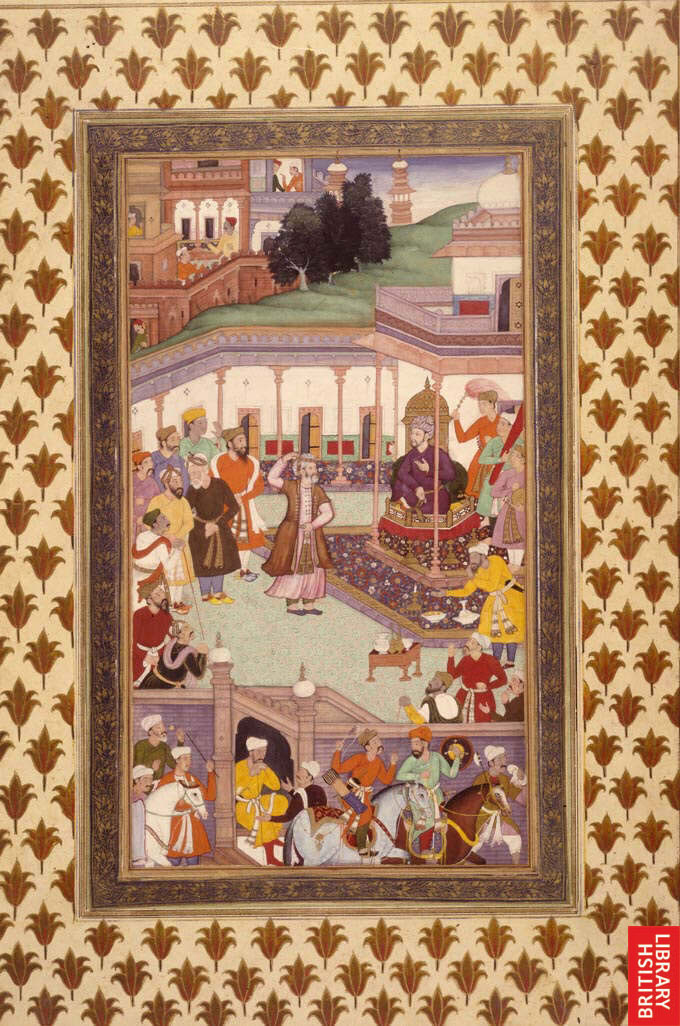

In the Tujuk-i-Jahingiri, a historical document from the reign of Emperor Jahangir, we find a comprehensive description of the celebration of Ramazan and Eid al-Fitr. By this time, many of the formalized etiquette and practices established by Akbar had become a permanent part of the Mughal tradition. In this memoir, Emperor Jahangir recounts his experiences during the holy month of Ramazan. He describes how he would leave his throne and make his way to the Idgah, where he was met with enthusiastic crowds who expressed their gratitude and bestowed gifts upon him. After completing his duties, he would make his way back to the palace to issue orders for charitable donations to be sent to numerous saints and religious institutions. He mentions, “I commanded a sum of money to be spent on alms and charity. Some lakhs of dams were entrusted to Dust Muhammad (afterward Khwaja Jahan), who divided them amongst faqirs and those who were in want, and a lakh of dams each was given to Jamalu-d-din Husain Anju (the lexicographer), Mirza Sadr Jahan, and Mir Muhammad Riza Sabzawari to dispose of in charity in different quarters of the city. I sent 5,000 rupees to the dervishes of Shaikh Muhammad Husain Jami and gave directions that each day one of the officers of the watch should give 50,000 dams to faqirs.” He also promoted and presented his courtiers and noble officers on this occasion.

(Emperor Jahangir at the gathering for the Eid al-Fitr, via Museum of Islamic Art,2008)

During the reign of Emperor Shahjahan, Eid al-Fitr celebrations were observed with great pomp and grandeur. In 1628 CE, during Emperor Shah Jahan’s reign, Mughal courtier Hamiduddin Lahori recounts the Ramazan and Eid al-Fitr festivities. He mentions During Ramazan, Sadr Musavi Khan welcomed underprivileged individuals and provided relief, including 30,000 rupees in donations and regular allowances. On June 3, 1628, the crescent moon brought joy and music. The next day, on Eid, princes, nobles, courtiers, and state officials gathered in the grand audience hall to express congratulations and well wishes to the emperor. He participated in a ceremonial procession to the Eidgah, offering prayers, and distributing gold among the people during the royal process.

Munshi Chandra Bhan Brahman, another courtier of Shah Jahan, vividly describes the grand royal procession to the Eidgah, a grand spectacle where the emperor emerges from the palace for public prayers. The city is on display, with houses and bazaars adorned with vibrant brocades. A multitude of individuals from surrounding towns and villages flock to the capital, filled with anticipation to catch a glimpse of their ruler. The royal route and surrounding grounds are meticulously arranged and beautifully designed, with regiments of mounted and infantry soldiers armed with matchlocks, rocket launchers, and flags. Sideshows fill the air with the resounding melodies of trumpets, bugles, and clarions. The emperor gracefully makes his way to the Eidgah, seated on a splendidly adorned horse or atop a majestic elephant. The atmosphere is both solemn and festive, with a lavish procession. During the royal process, significant amounts of gold are distributed among the general population. The emperor then makes his way to the Eidgah, where he humbly bows his head to the ground. The individual who delivers the Khutba for each imperial title is bestowed with robes of honor and monetary rewards by the emperor. Emperor Shahjahan paid an Eid-ul-Fitr visit to Jama Masjid in July 1656, shortly after its completion. On this occasion, the entire route from the front of Naqqar Khana inside the fort to the mosque ‘was flanked by two rows of elephants with gold and silver housings, besides a great many musketeers, matchlock and rocketmen’ (Liddle,2017).

Following Shah Jahan’s death and the takeover by his son Aurangzeb, fundamental changes occurred in the way Eid al-Fitr was observed. He had a puritanical mindset and set out to correct what he saw as moral laxity, resulting in increased austerity, orthodoxy, and court rituals. (Liddle,2017). He also constructed a separate Eidgah in Paharganj and offered prayers there instead of the Jama Masjid built by his father, Emperor Shahjahan (Safvi, 2019). It appears, however, that this austerity was quickly lifted following Emperor Aurangzeb’s demise in 1707 CE; his successors proceeded to celebrate Eid al-Fitr with the same fanfare, albeit with restricted means and authority.

(Aurangzeb built the Shahi Eidgah or place to offer prayers on Eid on outskirts of Shahjahanabad image via ranasafvi.com)

Eid al-fitr in final day’s of Mughal Empire

In Bazm-e-Aakhir, written by Munshi Faizuddin, the days of the last two Mughal Emperors, Akbar II and Bahadur Shah II, are recounted. One significant occasion during this time was the last Friday of Ramazan, known as Alvida. The Badshah would embark on a grand ceremonial procession to the Jama Masjid. He would sit on a silver chair beside an elephant and perform ablutions before entering the mosque. Princes and nobles followed him. The Badshah would request the imam to read out the khutba, a sermon, and then recite the names of all emperors who have passed away. The wardrobe superintendent would provide a robe to the imam, and the congregation followed suit. The imam would read the two raka’ats of namaz for Friday after the khutba. After completing his prayers, the Badshah would visit the asar sharif, a small enclosure housing the sacred relics of the Prophet. He would pay homage to the relics and return to the Qila. On the twenty-ninth day of Ramazan, envoys were sent to observe the moon, which would signify the end of Ramazan. When the moon was spotted or a letter confirming a sighting from a village, the moment to rejoice began. In the naqqarkhana, a 25-gun salute was given to commemorate the upcoming arrival of Eid al-fitr the following day. If the moon was not sighted, the gun salute would be done on the thirteenth day of Ramazan (Safvi,2018).

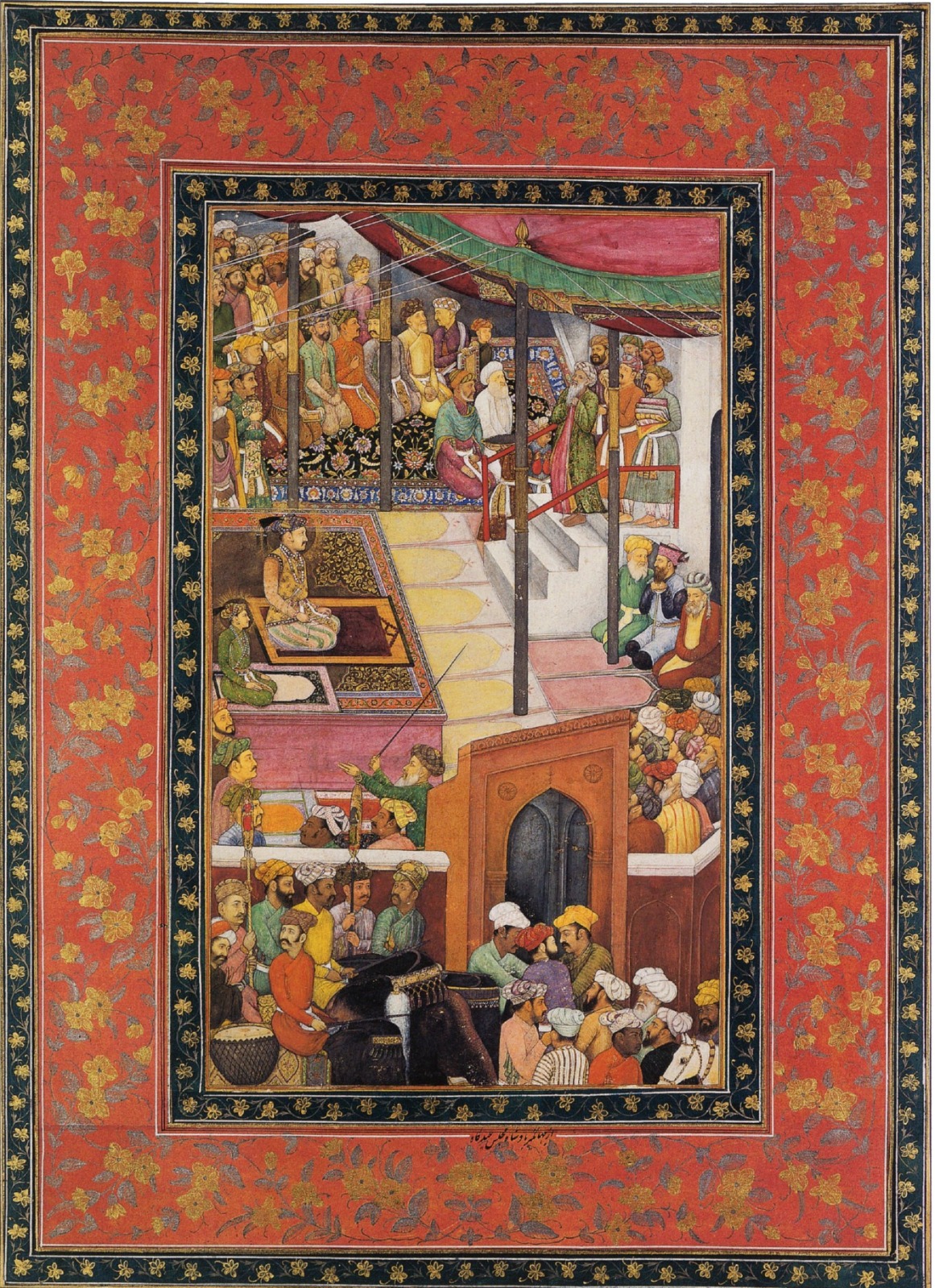

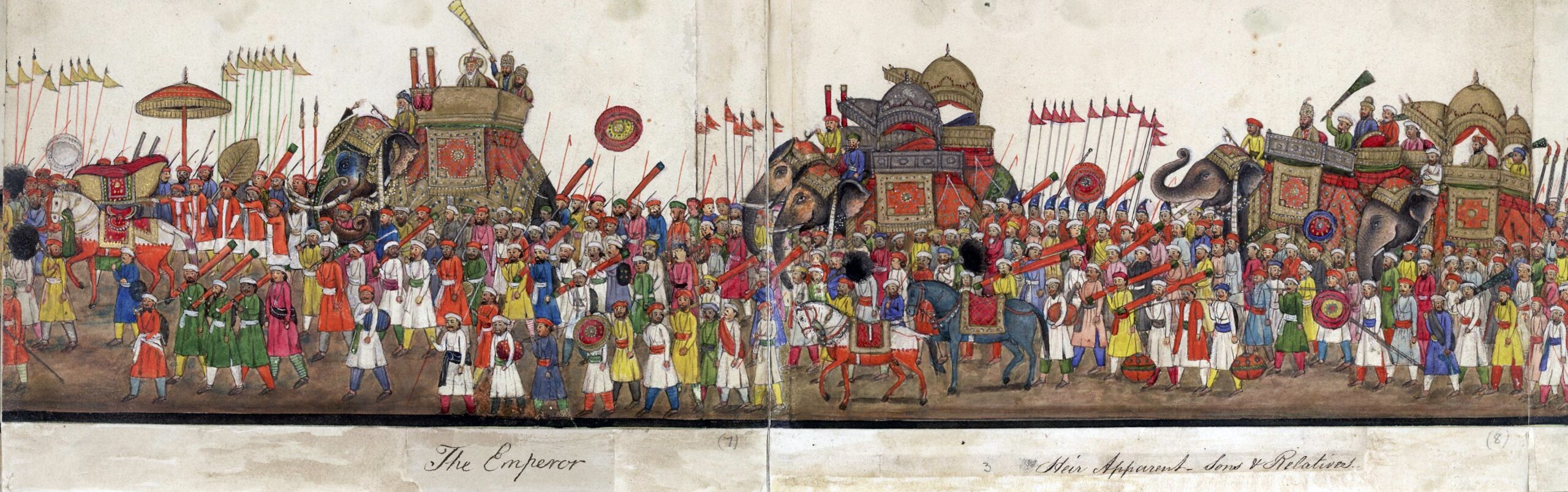

(A panorama in 12 folds showing the procession of the Emperor Bahadur Shah to celebrate the feast of the ‘Id., 1843, via British Library, 2009)

The Badshah, the next day would bathe and change into jewel-adorned robes before preparing to eat and drink. The procession began with a trumpet, and the Badshah would ride on his majestic elephant, symbolizing his power and authority. The royal procession would then divide into two, and the guns were fired again. The Badshah would then enter his hawadar, where he would address his subjects. The heir apparent sat in a palanquin, while the rest followed on foot.

After disembarking from the elephant, the Badshah entered the royal tent, where he would read the khutba. The armory superintendent fastened a sword and bow-and-arrow around the imam’s waist, and the imam read the khutba with a hand resting on the hilt of the sword. Upon the announcement of the Badshah’s name, the wardrobe superintendent presented him with another robe. A single gun was fired as a sign of respect for the khutba. The Badshah then returned to the Qila, where he held court in the Diwan-e-Khas. He accepted offerings and bestowed garlands and turban emblems upon them. He then entered the mahal and took his seat on a magnificent silver throne, graciously receiving offerings from all the noble ladies in attendance (Safvi,2018).

Thus, the festival of Eid al-Fitr transformed from a simple celebration into a grand event in the Mughal court. It was observed with great splendor and extravagance, except for a short period during Aurangzeb’s reign. The lavish display of wealth and power during Eid al-fitr in the Mughal court was not only a reflection of the Emperor’s authority but also a strategic maneuver to solidify political alliances and maintain control. The festival served as a platform for showcasing generosity, charity, and the distribution of power among courtiers, highlighting the intricate dynamics of the imperial court.

References

- Babur. The Baburnama: Memoirs of Babur, Prince, and Emperor. United Kingdom, Random House Publishing Group, 2002.

- Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri: or Memoirs of Jahangir: Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri: or Memoirs of Jahangir – Henry Beveridge, Alexander Roger, and Nuru-d-din Jahangir’s Royal Chronicles. India, Prabhat Prakashan, 1978.

- Iftikhar, Rukhsana. (2019). Genesis of Muslim Culture and Co-Existence in the Mughal Era. Journal of Islamic Thought and Civilization. 09. 119-130. 10.32350/jitc.91.08.

- Safvi, Rana. Shahjahanabad: The Living City of Old Delhi. India, HarperCollins India, 2019.

- City of My Heart: Four Accounts of Love, Loss and Betrayal in Nineteenth-Century Delhi. India, Hachette India, 2018.

- Richards, John F.. The Mughal Empire. United Kingdom, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- Liddle, Swapna. Chandni Chowk: The Mughal City of Old Delhi. India, Speaking Tiger Books, 2017.