Imagine the rhythmic sounds of two wooden shuttles of a loom going back and forth, synchronised with the weaver’s cadence while weaving cotton threads into a beautiful six-yard saree with intricate motifs and a thick border. This traditional handloom from Bengal, which originated in Medieval India and continues to date, is called Tant. A quintessential item in almost every Bengali wardrobe, Tant is favoured for its soft and breathable fabric conducive to the harsh and sultry summers of the region.

Traditional Handloom Weaving

Source: ARTS of INDIA

Handloom: Intrinsic to Indigenous Communities of Bengal

Archaeologists have traced the origins of cotton as far back as the Neolithic period of the Indian subcontinent (Moulherat et al. 2002) and observed its proliferation from the Harappan Civilisation onwards. A fabric known as dukula, a fine and expensive cloth produced in Bengal, finds mention in various ancient Indian texts like Arthashastra, Mahabharata and the commentary on the Acharanga sutra (Gopal 1961). Surprisingly, cotton is less notable in early classical literature due to its use by the masses and not by the elite (see Gopal 1961: 61 and references therein). For centuries, and possibly even more, traditional loom weaving has been considered as important as agriculture to the local indigenous communities of Bengal. It is a complex, demanding, elaborate and laborious artisanal skill, but still the primary source of livelihood for many communities in rural West Bengal. This industry gained immense recognition and flourished due to royal patronage during the time of the Mughals. However, with the advent of colonial rule, the handloom industry suffered massive losses and was on the brink of extinction.

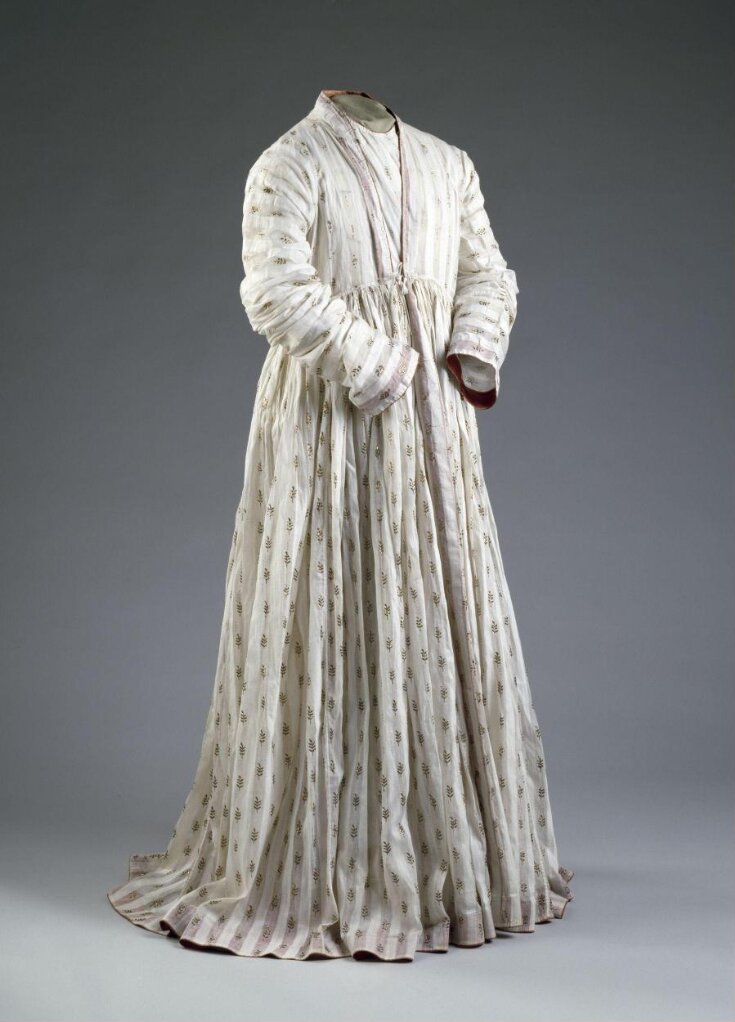

Bengali Muslin

The fate of the famed Bengali muslin from Dhaka was even worse due to British rule. This extraordinary material, made entirely out of cotton fabric and woven on traditional looms, had a high thread count, between 800-1200, a feat considered nearly impossible today. This muslin is produced from a specific variety of cotton called Gossypium arboreum var. Neglecta, locally known as Phuti Karpas, and is endemic to Bangladesh. Due to its high thread count, this fabric was unbelievably soft and had a high global demand amongst the nobility. The Arthashastra and The Preiplus of the Erythraen Sea describe the novelty of this fabric (Khatun 2015) while Mughal poets described it as light as air: baft hawa (woven air) or water: abe rawan (running water) and pleasant as the morning dew: shabnam (MAIWA). Tragically, this fabric and its source, the plant, met a brutal end with colonial rule. Now a GI-tagged handloom, it is slowly being revived to its former glory by Saiful Islam (see History – Bengal Muslin).

Man’s robe (Jama) is said to have belonged to Tipu Sultan of Mysore (d.1799) of white cotton muslin embroidered with gold, India, 18th century.

Source: Jama | Unknown | V&A Explore The Collections

The Versatile Tant

Tant is a versatile woven cotton fabric with many varieties that warrant their separate categories. Not only is it ideal for daily wear because of its light and airy fabric, it comes with an array of design elements, motifs and colours. Tant varieties get their name from the handloom cluster (village or city) they originated from, with unique weaving methods, patterns and motifs. Notable amongst those from West Bengal are the eponymous Dhanikhali, Shantipur, Phulia, Tangail (originally from Bangladesh) and Kenjakura. The classic Lal Paar Korial, Garad, and Baluchari style sarees are often adopted for cotton fabric but are popularly associated with silk.

Sun-drying dyed cotton yarn

Source: Avishek Das for MASH India

Jamdani

Along with Muslin, the Jamdani technique also received royal patronage during Mughal times. It has earned a well-deserved spot in the UNESCO list of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, and in 2016, Bangladesh received the Geographical Indication (GI) tag for Jamdani. The erstwhile district of Dhaka was the epicentre of the production of Jamdani fabric during the Mughal rule and was traditionally known as the ‘flowered muslin’ from Bengal (Khatun 2015).

Karuna Ezara Parikh (@karunaezara) in a white Jamdani saree by Coloroso Calcutta C O L O R O S O (@colorosoweaves)

It highlights the skills and design fortitude of the weavers as the Jamdani designs are woven into the loom through a particular discontinuous weft technique (Datta 2018). This unique weaving technique has a vast repertoire of motifs heavily inspired by Persian design, like geometric patterns and zigzag lines and those inspired by nature, flora and fauna. The designs are classified as hazar-buti, rose-leaf, dora-kata, chand, tara-buti, dabutar-khop, angurlata, kalka, kach, karalla, dalim, hapai, maḍuli, dooring, batpata, sandesh, chand, kachulata, inchi, hazar moti, ring, baghnali, panpata, kajallata, pona, mayur, pachh, dokla, anaras and panphul, to name a few (see further Khatun 2015; Datta 2018). Unlike the Bengali muslin, Jamdani survived the oppressive colonial textile laws, for it was adopted as a design element for sarees of cotton (Tant) and other fabrics (Khatun 2015).

The GI-Tagged Handlooms of West Bengal

Baluchari, Dhanikali and Shantipuri handloom and sarees are widely popular Bengali sarees. Baluchari sarees are notable for their ornate and intricate designs based on the Bishnupur Temple Architecture, generally designed for silk fabric. However, Baluchari design elements on Tant are also well-liked by Bengali women.

A woman preparing cotton yarn

Source: Artisans: Bengal Weavers– MAIWA

Most of the literature will point out that the Shantipuri Tant is the oldest Bengali textile to have survived, with its origins going back to the 15th century. However, it was only during the 17th century when the Shantipur handloom industry got established with Mughal patronage, and the sarees were exported far and wide to Turkey, Greece, parts of Arabia, Iran and Afghanistan (Mitra et al. 2009). These are coveted for their high thread count and soft fabric, simple design and the sarees have a unique extra warp on the border. Although cotton is the primary fabric for this handloom, the saree borders are decorated with other textiles, including silver and gold zari. The Paisley designs are frequently observed on these sarees amongst a host of design elements like “Nilambari, Gangajamuna, Benkipar, Bhomra, Rajmahal, Chandmalla, Anshpar, Brindabani Mour Par, Dorookha” to name a few (Mitra et al. 2009). The neighbouring village of Phulia is also a big handloom and saree weaving centre for Shantipuri Jamdani and Tangail handloom.

Tangail Saree

Source: TheCrazyLooms

Tangail handloom originated in Bangladesh, but after the partition in 1947, many weavers of the Basak community settled in the district of Nadia, West Bengal (Basak and Paul 2015). The Tangail handloom of undivided India has been recorded in foreign travellers’ accounts of Ibn Battuta and Huen Tsang (Datta 2018). The present-day and recently GI-tagged Tangail of West Bengal fuses the traditional handicraft of Bangladesh and Shanitpuri-style and is produced in the Nadia and Purba Bardhaman districts. Tangail sarees are different from Shantipuri due to their paper-like finish and the extra-weft butis or small repeated motifs on the body of the saree.

Simplicity of Weaves

Kenjakura Products

Source: Kenjakura Tant | RCCH

The village of Kenjakura in the Bankura, West Bengal, is primarily a weaving community. They are known for producing brilliant gamchas or towels, sarees with subtle colours and simple geometric shapes like cheques, stripes, honeycomb patterns and flower motifs called phool toyla. Apart from sarees, dupattas and stoles, the weavers of Kenjakura make lovely household furnishing items like cushion covers, curtains, and mats. Dhaniakhali sarees, or ‘Mamata sarees’ as they are popularly known, are a staple of the Trinamool Congress party leader. They are simple and subtle, with thin borders and stripes for design.

Dhanikhali Saree

Source: https://balaramsaha.com

Revival

The handloom industry is still a small-scale and relatively decentralised industry in India. According to the 4th handloom census by the Ministry of Textiles, Government of India, more than 35 lakh people are employed in this sector, with a lion’s share of the workforce, i.e. 72% being women. In West Bengal, more than 2 lakh handlooms employ more than 6 lakh people. Given these statistics, this industry is still in a state of crisis. Factors impeding its progress range from autocratic middlemen or Mahajans to competition with power looms and machine-made textiles, to low-profit margins and reduced capacity for capital, as well as expensive raw materials and lack of marketing, just to name a few. One of the major causes of the dwindling industry is that traditional handloom weaving is time and labour-intensive. The weavers get paid for the finished products rather than the time spent on each piece.

Currently, the Government of India, private organisations, designers and ateliers, are taking the initiative to revive and promote the Handloom Industry of India. For anything to survive, specifically traditional handicrafts, they need to evolve and meet the current needs of society without losing their identity. Datta (2018) summarises the steps taken to help with this endeavour like design intervention, where the weavers are exploring non-traditional raw materials, they are expanding their product portfolio by asserting themselves in the household furnishings sector, and are now being equipped and educated by experts in the field to help them upgrade their skills by linking them to institutes like NIFT, as well as West Bengal Khadi and Village Industries Board. For marketing, Central Cottage Industries Emporium and Handloom House, along with others, are assisting weavers with exhibitions and marketing strategies and removing the middlemen. An overall infrastructural improvement, yarn banks and resource and dyeing units have helped with easy access to raw materials and equipment.

Essentially, the India Cottage Industries, in general, and the Handloom Industry within it, are the guardians of regional cultures, traditions and rich Indian history. It remains a low to no-carbon emissions industry; the pieces are entirely handmade with no dependency on electricity, and each piece is unique and has the quality to last for decades (Jones, 2020 www.ygncollective.com). Their survival and proliferation should be of primary importance in this globalised world. For this, they must overcome substantial obstacles and survive the onslaught of modern-day industry standards, the high demand of consumers, and supply-chain management while preserving their artistic skills and integrity. In doing so, they help uphold the cultural identity of the country.

References

Basak, N.K. and Paul, P. 2015. Origin and Evolution of the Handloom Industry of Fulia and Its Present Scenario, Nadia District, West Bengal, India. Economics 4(6): 132-138.

Datta, DB. 2018. An in-depth study on jamdani and tangail weavers of Purba Bardhaman District, West Bengal, India. Journal of Textile Engineering & Fashion Technology. Vol. 4(3):263‒270. DOI: 10.15406/jteft.2018.04.00150

Dubey, P. and Santra, S. 2013. Weaving and Livelihood in Shantipur of West Bengal: Past and Present. International Journal of Current Research. Vol. 5(12), pp. 4014-4017.

Gopal, L. (1961). Textiles in Ancient India. Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 4(1), 53-69. https://doi.org/10.2307/3596207

Khatun, S. 2015. The Jamdani Sari: An Exquisite Female Costume of Bangladesh. Traditional Knowledge and Traditional Cultural Expressions of South Asia, (ed.) Sanjay Garg. Sri Lanka: SAARC Cultural Centre.

Mitra, A., Choudhuri, P.K. and Mukherjee, A. 2009. A diagnostic report on cluster development programme of Shantipur handloom cluster, Nadia, West Bengal Part I – Evolution of the cluster and cluster analysis. Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge. Vol. 8(4), pp. 502-509.

Moulherat, C., Tengberg, M., Haquet, J., & Mille, B. (2002). First Evidence of Cotton at Neolithic Mehrgarh, Pakistan: Analysis of Mineralized Fibres from a Copper Bead. Journal of Archaeological Science, 29(12), 1393-1401. https://doi.org/10.1006/jasc.2001.0779

What is Traditional Loom Weaving? YGN Collective | Artisan Goods

The ancient fabric that no one knows how to make

- May 15, 2024

- 6 Min Read