Female Bhakti Saints and the Challenge to Patriarchy

- EIH User

- August 30, 2024

PERCEPTIONS OF THE FEMININE

In Hinduism, a woman embodies shakti, the original energy of the universe. However, the Brahmanical orthodoxy did worship the divine feminine yet deprecation of the position of ordinary Women in Medieval Indian Society was practiced. The image of a woman as a temptress was deeply rooted in religious tradition and reinforced through myths and legends. Adding to this, a medieval period poet-saint writes the following,

vyāsa kanaka aru kāminī, tajiyai bhajiyai dūrī harisauṃ aṃtara pārihaiṃ, mukha dai jaihaiṃ dhūri – Śrī Harirāma Vyāsa, Vyāsa Vāṇī, Siddhāṃta Kī Sākhī

“One should avoid and run away from the desire of Kanak (money) and Kaamini (beautiful girls), for He can easily be distracted from the affluence of Hari Bhajan (devotion) and ultimately suffers.”

Here it’s apparent that to lead oneself on the devotional path to the Divine, it was advisable for a man to maintain a distance from kanak –wealth and kamini-women. Julie Leslie has highlighted the prevalent notion that – women encountered spiritual hurdles due to their perceived proximity to the material world of physicality and relationships and the traditional notion about the ‘weakness’ of their womanly natures. Thus the journey of women towards self-identity and self-expression faced considerable obstacles due to the patriarchal foundations of society, economy, and even language. In such a situation women striving for spiritual freedom in Hinduism, through self-expression, necessarily appeared deviant.

In such a socio-cultural milieu, the emergence of the Bhakti Movement and female rebels offered a counter-narrative that challenged traditional gender norms and provided a platform for female spirituality to flourish.

TRACING THE BHAKTI MOVEMENT

The Bhakti movement began in South India between the 7th and 10th centuries, with the Alvars and Nayanars composing devotional poems in Tamil to Vishnu and Shiva, respectively. Bhakti soon spread to North India, notably through the 10th-century Sanskrit text, the Bhagavata Purana. Within this Medieval Indian Bhakti Movement, the devotional practices included reciting the deity’s name, singing hymns, wearing identifying emblems, and undertaking pilgrimages, effectively deinstitutionalizing religious practices.

Bhakti represented a return to the universal language of daily life, with its music and poetry serving as both spiritual guides and social records of the poets’ experiences. The works created by passionate women, expressed deep personal emotions, blending divine devotion with human intimacy and sensuality underscoring the birth of a new relationship between patriarchy and Hindu Bhakti Saints – one that of both devotion and dissent.

THE VARIED VOICES OF FEMALE BHAKTI SAINTS

“In the Bhakti movements, women take on the qualities that men traditionally have. They break rules of Manu that forbid them to do so. A respectable woman is not, for instance, allowed to live by herself or outdoors, or refuse sex to her husband- but women saints wander and travel alone, give up husband, children and family.”

– A.K. Ramanujan, ‘Talking to God’

A few female Bhakti Saints in India, such as Akka Mahadevi, Andal, and Meerabai, are well-known beyond their regional contexts. In contrast, figures like Karaikkal Ammaiyar, Soyarabai, and Lal Ded, whose lives and work provide insights into inequality and discrimination, remain less recognized. The legacy of many of these women saints is preserved primarily through oral traditions and hagiographic accounts.

(https://jaggerylit.com/)

Andal: A pioneering figure in the Bhakti movement in Tamil Nadu, she is the only female Alwar whose compositions are included in the revered ‘Nalayira Divya Prabandham,’ a collection of 4,000 Tamil verses. As a child, Andal was found abandoned in the garden of Periazhwar, a devout Vishnu follower who made garlands for the temple, he adopted her naming her Kothai. It is poignant that even in this narrative, within a patriarchal society, a female deity finds acceptance only after being adopted by an upper-caste family. Andal’s upbringing in a Brahmin household nurtured her deep devotion to Vishnu later expressing a desire to marry Lord Ranganatha, a form of Vishnu.

(sarweshshah.me)

Karaikkal Ammaiyar: One of the 63 revered Nayanar mystics from Tamil Nadu, she is celebrated for her deep devotion to Lord Shiva. Abandoned by her husband, who saw her as a goddess after witnessing her miracles, Ammaiyar was ostracized by a society that could not accept a married woman living alone. This harsh judgment led her to renounce conventional beauty and social conformity, seeking instead a life of spiritual asceticism.

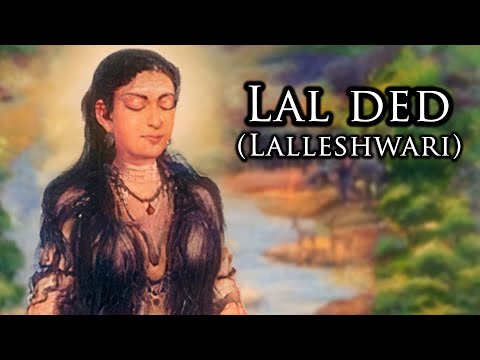

Lal Ded: Born into a Kashmiri Pandit family in the 14th century, she left her oppressive marriage to follow a path of devotion to Shaivism. Her vakhs, or poetic verses, are some of the earliest known works in Kashmiri literature. After severing her material ties, Lal Ded is believed to have wandered unclothed, symbolizing her rejection of worldly attachments in favor of a spiritual existence. Her writings often featured sexual metaphors, to convey spiritual freedom and insights rather than materialistic desires.

(quora.com)

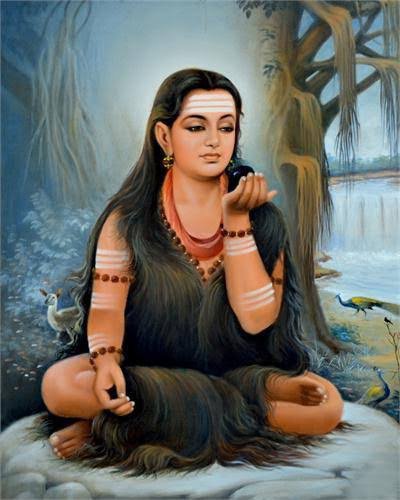

Akka Mahadevi: She was a 12th-century Shiva devotee from Karnataka, and is renowned for her vachanas, which express her frustration with societal norms inherent in the relationship between women saints and patriarchy. Married to King Kaushika, she rejected the conventional life, eventually renouncing her royal ties and wandering naked, covered only by her hair, in search of her Divine Lover, Shiva.

(https://www.dollsofindia.com)

Mirabai: A Rajput princess turned poet-saint, she is renowned for her bhajans dedicated to Lord Krishna. Her verses, rich in lyrical beauty and spiritual depth, also carry a strong feminist undertone, challenging the rigid societal norms of her time. Mirabai’s unwavering devotion led her to renounce her royal duties and her marriage, embracing a life of Spiritual Freedom in Hinduism which defied the expectations placed on women in her era.

(https://storymirror.com/read/marathi/poem/snt-soyraabaaii/5908yewq)

Sant Soyarabai: Belonging to Mahar caste, she was a woman from Maharashtra, who lived a life rooted in devotion to Lord Vithoba while navigating the challenges of caste and gender. Unlike many other women saints who rejected marriage, Soyarabai found spiritual freedom within her domestic life. Her abhangas vividly depict the struggles of daily life, caste oppression, and her deep devotion, highlighting her heightened awareness of both gender and caste issues reflecting an altogether varied dimension of Bhakti Saints and Cultural Rebellion.

These women Bhakti saints came from diverse backgrounds—some were prosperous, others impoverished; some were married, others single; they belonged to various castes, from Brahmins and Rajputs to Shudras. Despite their differences, they shared a common resolve to express their devotion. The Bhakti Movement and Female Rebels boldly challenged male-dominated spaces, marching forward with unwavering determination.

THE NATURE OF BHAKTI AND GENDER DYNAMICS

A key aspect of Bhakti poetry was its portrayal of the soul’s union with God through the metaphor of romantic love. Bhakti poetry frequently adopted a female voice, often that of a bride yearning for her absent husband. This literary trope sometimes led to a paradox where male devotees, by adopting an idealized female persona, could represent ‘feminine’ qualities, while actual women faced disadvantages due to societal perceptions of their ‘natural’ femininity.

Uma Chakravarti sheds light on the Bhakti Movement and gender equality, she notes that while male bhaktas could integrate household life with devotion, females faced significant challenges reconciling family responsibilities with their spiritual pursuits. Women like Meera Bai and Bahinabai faced considerable resistance due to their devotion, which was often perceived as a threat to traditional family structures. The societal view of women loving a divine figure, even Krishna, was seen as a transgression of dharma and social expectations.

To overcome these barriers, some women in medieval Indian society completely abandoned their household duties, while others challenged their parents or chose to live independently. Figures like Andal devoted themselves solely to their spiritual practice, illustrating the diverse paths women took to reconcile their devotion with societal expectations.

REIMAGINING FEMINISM THROUGH WOMEN BHAKTAS

A paradox related to gender roles in Bhakti tradition raises the argument that female poet-saints merely shifted from ‘slavery to husband’ to ‘slavery to god’, exemplifying that the wife takes on a relation of generalized subalternity to her lord-husband. However we must refer to what Tanika Sarkar suggested, highlighting how a feminist appeal to universal rights “does not at all mean wiping individual lives clean of community and cultural influences. It means simply not allowing them mandatory powers even when the individual rejects certain aspects of them. It also allows the individual to select, move away, and deny aspects of the culture into which she is born. Only within a horizon of freedom can she have a meaningful relationship with her cultural life world”. Thus the ability of women in medieval Indian society to choose their individualistic orientation and the subject of their devotion conveys the embracing of non-conformity to societal and familial expectations and having the power to craft their own choices. Historical figures like Lal Ded & Akka Mahadevi, often exhibited characteristics and actions aligned with feminist ideals, even if they didn’t identify consciously as feminists themselves. The core principles of feminism—such as advocating for gender equality, challenging stereotypes, and combating discrimination—can be identified in the actions and writings of the female Bhakti saints in India, even if they didn’t use the term “feminism” as we understand it today.

CONCLUSION

The medieval period witnessed the contradictory notions of femininity, ascribed on one level the status of divine primordial power while temporally being treated as mere subjugated objects of ownership defining a social setting based on gendered hypocrisy and hierarchical convenience. In the wake of the Bhakti movement, women poet-saints like Mirabai and Akka Mahadevi diverged from traditional feminine ideals. While obliterating the cultural perception of a woman being an obstruction in the path of salvation, they embodied the process of empowerment and completely neglected the image of a woman as a temptress.

References –

https://feminisminindia.com/2017/04/03/bhakti-movement-women/

https://feminisminindia.com/2019/07/05/andal-desexualised-mother-and-her-erotic-desires/

https://janataweekly.org/roots-of-feminist-fervour-women-in-bhakti-movement/

Ramaswamy, Vijaya. “Rebels — Conformists? Women Saints in Medieval South India.” Anthropos, vol. 87, no. 1/3, 1992, pp. 133–46. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40462578. Accessed 25 Aug. 2024.

Pande, Rekha. Divine sounds from the heart—singing unfettered in their own voices: the Bhakti movement and its women saints (12th to 17th Century). Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2010.

Julie Leslie, ‘Essence and Existence: Women and Religion in Ancient Indian Texts’, in Pat Holden, Women’s Religious Experience, p 93-7

RAMASWAMY, VIJAYA. “Rebels, Mystics or Housewives? Women in Virasaivism.” India International Centre Quarterly, vol. 23, no. 3/4, 1996, pp. 190–203. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23004619. Accessed 26 Aug. 2024.

Tanika Sarkar, “A Prehistory of Rights: The Age of Consent Debate in Colonial Bengal,” Feminist Studies 23, no. 3 (2000): 601–22, quotation on 618–19

- Bhakti Movement and Female Rebels

- Bhakti Movement and Gender Equality

- Bhakti Saints and Cultural Rebellion

- Female Bhakti Saints in India

- Gender Roles in Bhakti Tradition

- Medieval India Bhakti Movement

- Patriarchy and Hindu Bhakti Saints

- Spiritual Freedom in Hinduism

- Women in Medieval Indian Society

- Women Saints and Patriarchy