Finding the Queer in Delhi& #39;s Lanes: Significance of Akhil Katyal& #39;s Delhi Poems in Queering Spaces

- EIH User

- April 10, 2024

Throughout its historical existence of several centuries, several poets have written extensively about the city of Delhi. While some of them such as Ghalib and Mir Taqi Mir have written poems of lament, i.e. shahr-e-asob, highlighting the socio-political decline of the city, other poets have covered the city as a site of conflict and trauma post the Partition of India. Agha Shahid Ali’s poetry, however, changed this trend as it moved beyond the depiction of the city as a site of conflict and explored other themes that are now heavily associated with Delhi such as desire and memory. Akhil Katyal, a contemporary poet-professor, who has been influenced by Shahid’s poems on Delhi, uniquely depicts the city as he uses the city’s geographies to re-imagine the city. His poems not only depict the invisiblised queer community and the oppression faced by it but also celebrates queer desire, relationships, and activism. This essay examines how Akhil Katyal’s Delhi poems reimagine the city and bring to attention the struggles, desires, and victories of the otherised queer community, moving away from a heteronormative depiction of the city and hence, queering the space.

Though the capital of India, Delhi has been a city known for being unsafe for gender and sexual minorities, and hence, gender minorities have not been able to access and enjoy the public spaces of the capital as much as the cis-het men have been able to. Historically speaking, not only have queer individuals been denied access to public spaces and resources but for the largest time the community has not been accepted as homosexuality has been considered illegal and even an offense. In order to battle such fierce obstacles, the law in itself has not proved to be sufficient for queer individuals continue to face severe homophobia, discrimination and harassment even after decriminalisation of homosexuality in several nations. The issue concerns far larger factors than the law and homosexuality is still considered to be an issue of social taboo. Hence, more measures than mere decriminalization are required to combat homophobia. One of the most important ways to challenge such social attitudes is by the reclaiming of public spaces by the queer community. Reclaiming public spaces refers to the act of claiming access to public spaces such as parks, historical monuments, markets etc. by individuals of a marginalised and otherised social group who have historically not been allowed to access such spaces or discriminated against while doing so. Such reclaiming does not merely lead to laying claim to a public space but also laying claim to the queer identity in that space. Reclaiming public spaces, though does not end homophobic attitudes yet it plays a significant role in assertion of the queer identity in a public space and hence challenges the otherisation and exclusion of the queer community.

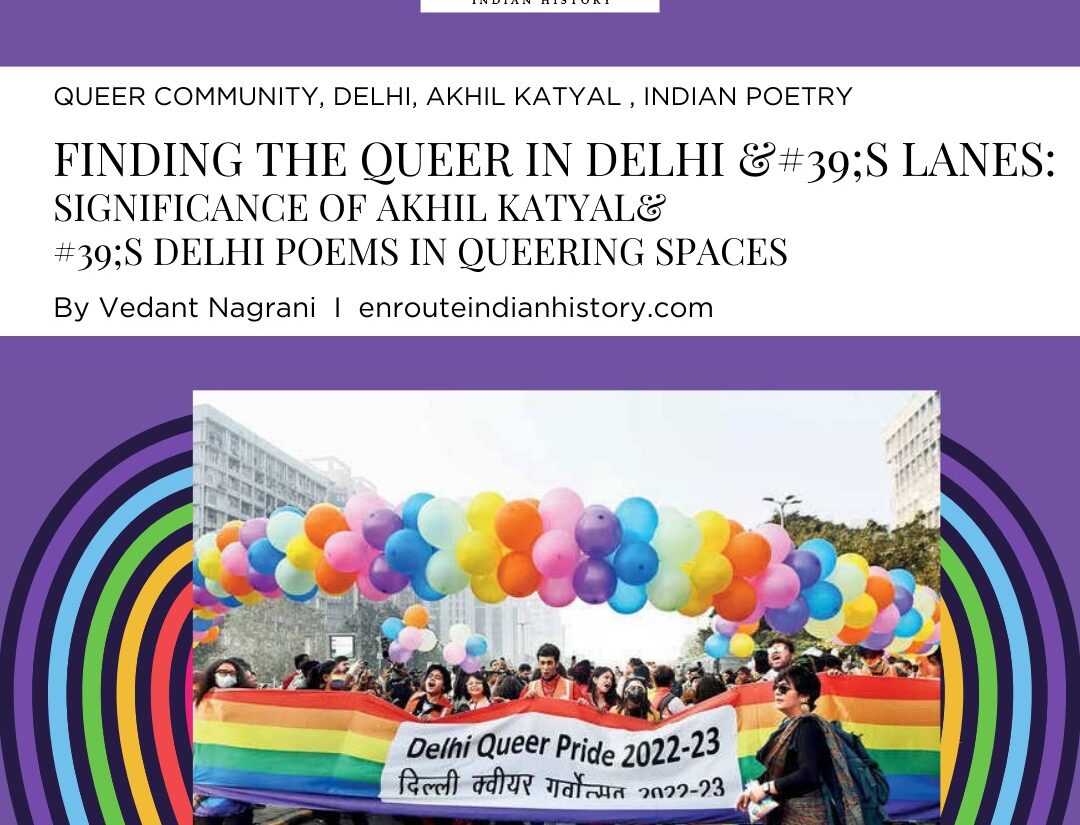

Akhil Katyal, a Delhi-based poet has played a significant role in depicting the many shades of the queer community in Delhi often using irony, sarcasm, and witty humour apart from realistic depictions of everyday discrimination and homophobia. In his poem “The Barakhamba Road/Tolstoy Marg Crossing”, he depicts Delhi in its many shades as the city gears up for Delhi Queer Pride, an annual pride march held in November in the Tolstoy Marg area of the capital where thousands of queer individuals and allies gather for a march of celebration and resistance. The poem also depicts the diversity within the queer community as well as the importance of the pride march as it traces the journey of several individuals from different parts of Delhi such as Shahadara, Saket, Vishwavidyalaya who are united by the desire to be a part of the march:

An odd, white handkerchief tied on his arm,

he gets onto the metro at Vishwavidyalaya.

With a stuffed back-pack on her shoulder,

she boards the bus at Shahdara.

In his grey track pants,

he hails an Ola from Saket,

With her phone in her back-pocket,

she climbs onto a Haryana Roadways bus.

The red glass bangles he’d bought yesterday

reflect the winter sun; his fingers dance.

She pulls out a crumpled rainbow muffler

and waves it to her from across the road.

He sees a small tear in the stockings as he

pulls down the track pants but doesn’t care.

At that Crossing she knows from the map, she

sees a big crowd – and turns her phone to silent.

A photograph of the 2022-23 Delhi Queer Pride march

Courtesy: Riya Sharma and Divya Kaushik, Times of India

Katyal does not merely depict the city and queer the city. Rather, he goes a step further and also reimagines the geography of the city and infuses it with his imagination of human bonds. His depiction of his relationship with his partner seems impossible to imagine in isolation without Delhi which is such an important site for him. As his relationship matures with time, so do his imaginations of it in the city’s spaces. That is, the temporalities of his relationship are depicted in relation to the many spaces and parts of Delhi:

He was as arrogant as a

Chattarpur farmhouse but

in the end, I figured he was

just cluttered, like Adhchini.

Which I liked. Our beginnings

were rocky, we held hands,

infrequently, and uneasily,

like Def Col and Kotla,

but then, in some years,

often and more breezily,

like Jangpura & Jangpura

Extension. All those years,

of romance and apprehension,

he’d held me in his Najafgarh

arms and kissed me like

Shalimar Bagh. Not that we

didn’t fight like Rajouri,

crossing each other’s Civil

Lines, not that he wasn’t at

times distant like Greater

Noida, or quiet like Asola,

but always, when the worst

had passed, we returned at

last, to where we’d been, some

where near Dilshad Garden,

by the blessings of Nizamuddin.

In one of his poems titled “Jangpura Extension”, Katyal beautifully depicts a rainy day in the Jangpura Extension with his partner. The poem not only locates the queer desire in the poet and his partner’s bond but also in a 50 year-old Sikh man who approaches the poet in an act of “cruising” after he drops his partner at the JLN metro station. Initiating the conversation by asking him directions for the ‘Khanna Market’, a misnomer for Khan Market, he offers to drop the poet to Lodhi Garden where he wanted to go.This depiction of the 50 year-old Sikh man functions at three levels. First, it depicts the many layers of queer desire and its marginal existence as the poet himself takes some time to realize that the Sikh man is cruising due to its discreet nature. Second, it also depicts the importance of geography of the city as Lodhi Garden, the poet’s destination, is a site of desire and one of the rather few spaces where queer individuals can still engage in acts of love. Third, it also deconstructs the prejudice associated with the queer community and its imagination as a “Western idea”, “a phase” or as a “trend of today’s youth” as it depicts a 50 year-old man desiring same-sex love. He is more or less of the same age as that of the people who harbor such prejudices and hence the poem effectively challenges such ideas:

The Latin word for the

ear is “pinna”, wings.

I knew why this morning

as you held me between

finger and thumb, I was only

cartilage ready to fly –

you woke up, and outside

the rain made even the petals

of bougainvillea so heavy,

that the plants had to

shed them, filigreeing the

pavement with the

colour of sunrise, and later

as we walked towards the

stadium, we waded through

remnants of the sun,

attenuated under our feet,

as “the earth,” was

“thawing from longing

into longing.” You said bye,

took the metro, and I

walked on past noon.

When turning near JLN,

a Maruti stopped by, a

man, about fifty, Sikh,

asked me the directions for

Khanna Market; when I told

him, he said “Come I’ll

drop you.” I said “I am

going to Lodhi Gardens.”

Again, “Come I’ll drop you,”

and it took me a second to

realise he was cruising; as I

looked, the sun was thawing

in his eyes. I said “I’ll walk.”

He took my answer and

crushed it on the road.

In another poem titled “For Someone Who Will Read This”, the poet imagines how the world would be 500 years from the present. Using the frame of time and by locating the poem in the future, he satirizes the gender norms of the present as he imagines how

“our toilets for “men” and “women”/

must make you laugh”. Further, in his imaginary conversation with his future reader, he also asks the reader if the contemporary political crises such as that of Kashmir have been resolved or not, if Mumbai still stands by the sea and so on. In the end, he asks the reader for a favor:

Would you go to Humayun’s Tomb

in what used to be Delhi

and just as you’re climbing the front stairs,

near the fourth step, I have cut into

the stone wall to your left –

“Akhil loves Rohit”

Will you go and look at it?

Make sure it’s still there?

In this poem, though the poet is concerned with several political concerns, he asks the reader for a favor only for his personal relationship. This favor depicts how important the inscription on the monument is for the poet as well as other queer individuals. Though such inscriptions are also done by people not belonging to the queer community, they become very important for queer individuals as it is one of the only few spaces where queer love is knowingly or unknowingly acknowledged and accepted as the people passing by do not usually care to read such inscriptions carefully. Such inscriptions tend to defy the state’s narratives about the queer community and its lack of recognition of the community as they embed their confession to the walls of the monument and create a public memory that they hope will be timeless.

Much like Sunil Gupta’s photographs of Delhi, Akhil Katyal’s poems on Delhi do not merely capture the beauty of the city but also records and captures the marginalised and otherised queer community within the capital. As the aforementioned poems depict, his poems capture the various shades of queer love from cruising, inscriptions on public walls, community-making in pride marches and so on. His poems on Delhi are very relevant as they not only depict the queer community but they also queer the city itself. Rather than engaging in scathing and charged critiques of homophobia, his poems often use satire, irony, and humour to challenge societal attitudes towards the queer community making his poems much more accessible to his readers.

Works Cited

- Katyal, Akhil. “Delhi Queer Pride: Ten short poems by a city-based queer poet to mark a decade of pride.” Scroll.in, 12 Nov. 2017,

- Shah, Sonali. “Poet verses Delhi.” India Today, 16 Mar. 2020,

https://www.indiatoday.in/magazine/leisure/story/20200316-poet-verses-delhi-1652764-2020-03-06

- Ghoshal, Somak. “How do you hear a city like Delhi?” Mint Lounge, 10 Apr. 2020,