An Italian Scholar, Cardano, in 1564, remarked that playing card games is like an ‘ambush’ because of their concealed identity. The history of playing cards in Indian culture has evolved from being used for recreation to gambling and as a symbol of social status. People believe that the earliest playing cards in India were Patrakrida. However, the first written evidence of Playing cards in Indian history was in the 16th century. The written evidence suggests that the earliest card games in Indian culture are associated with the Ganjifa cards. The word Ganjifa means Playing Cards originated in Persia in the 15th century, derived from the Persian word ‘Ganj’ or Treasury. The origin of the cards themselves is, however, debated. According to a Persian chronicler of the 17th century, the Ganjifa card game and its playing cards were invented by Mirza Giyath al-Din Mansur. It considers Ganjifa, an adaptation of the European card game. Later, Mehdi Roschanzamir rejected this theory. He argues that the Persian sources mention the Ganjifa card game existed before the Safavid period (1501- 1732). It was then probably played with chips carved out from Turquoise.

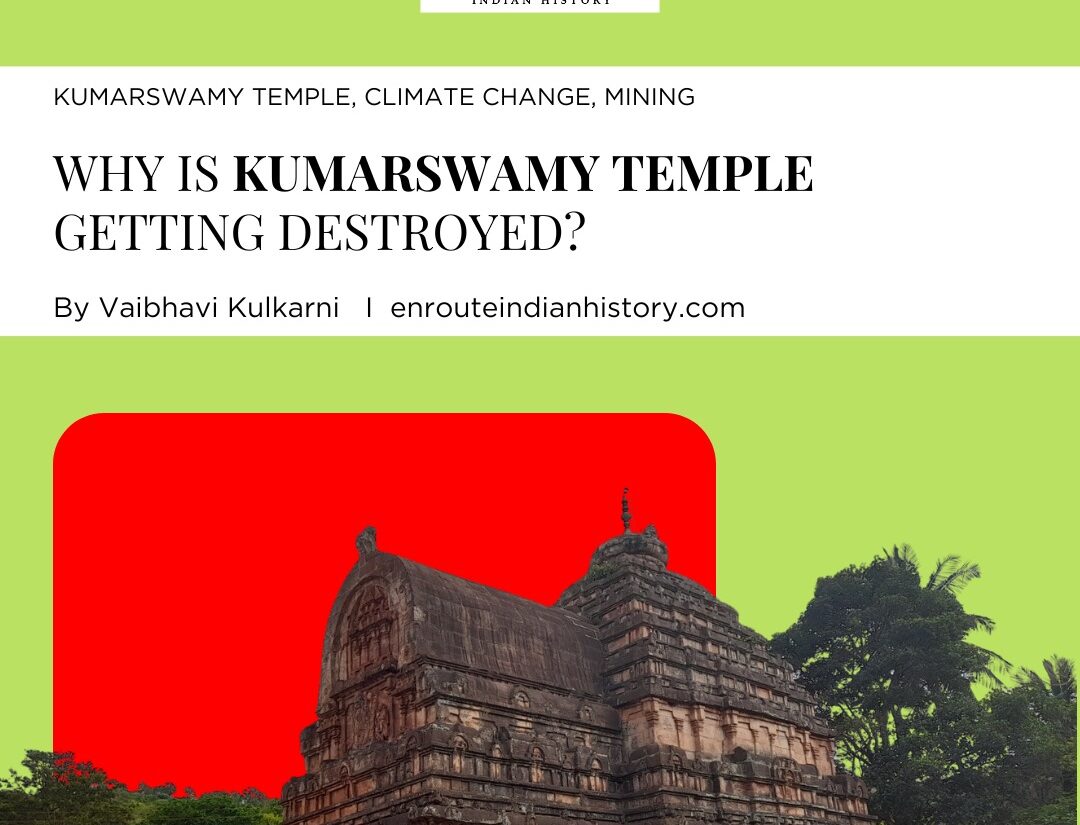

Mughal Ganjifa Playing Cards, Early 19th century, complete set, courtesy of the Wovensouls collection

The most accepted notion regarding the appearance of playing cards and card games is attributed to the entry of Mughals into the subcontinent. On the other hand, it is also plausible that the playing cards and card games traveled into the Indian subcontinent before the entry of the Mughals with the Turkman princes emigrating into the Deccan during the late 15th c. The playing cards of the card games in Indian culture consist of suits of equal value with an identical series of Numerals and court cards with the Raja as the highest among all. Traditionally cards in Indian culture were divided into three main categories. The eight-suited pack, the Hindu dasavatara deck includes ten suits, each depicting the incarnation of Vishnu. The third variant is the twelve-suited deck containing ninety-six cards, all having thematic references to the Hindu Ramayana epic.

Playing cards from Puri, Odisha, India, made with the traditional pattachitra technique. Courtesy: Wikipedia Commons

The first appearance of Ganjifa cards in Indian history was in the memoirs of Babur. These are circular cards with 2-12 cm diameter made out of ivory or tortoiseshell and painted with designs. In his memoir, Babur recounts gifting a pack of Ganjifa Playing cards to Shah Hasan during Ramzan in 1527. The Mughal emperor Akbar was also fond of card games and a detailed description of him playing cards is found in the Ain-i-Akbari. The cards used by Akabr was a 12-suitt deck called ‘Akbar Ganjifa’ but there are no extant specimens. However, a detailed description of the cards comes later in 1565. The earliest extant design of the Ganjifa card in Indian history comes from Ahmadnagar and is dated approximately around 1580, depicting the mir or king of the Surkh meaning gold coin. The earliest extant cards of Indian history to which a date can be attributed are a 75 Cards set of the Mughal Ganjifa whose first inventory date is 1674. The Mughal Ganjifa cards described by Ahli Shirazi ( Persian poet) belong to an eight-suited pack. These are Ghulam, Taj, Shamsher, Ashrafi, Chang, Barat, Tanka, and Qimash. The total pack consisted of ninety-six cards. Ten cards of each suit were number cards while the other two were court cards namely, mir and wazir.

Various Ganjifa cards from a 19th century Dashavatara set

India, Rajasthan, 19th century

Drawings; watercolors

Opaque watercolor on cardboard

Courtesy : LACMA

Indian history saw the development of other variants of Ganjifa playing cards and card games over time. The most prominent one was the one developed by Sri Krishna Raja Woodeyar III (1794-1868), ruler of Mysore. He was deposed on the pretext of alleged misrule by the Britishers and during this time, he spent a lot of time in mystical and astrological studies and also devised several card games that are mentioned in the work Sritattvanidi. His court painters produced several new cards for him ranging from thirty-six to 360 in number. In Orissa, the Game of Ganjifa and its cards are still played traditionally. Today, it remains the only state where cards are made through handcrafts rather than machines. The unique feature of the traditional playing cards of Orissa that are painted in the town of Paralakhemundi is that the story of Rama is depicted in cartoon strip format.

Ganjifa cards were very popular in the state of Rajasthan and the main center of manufacturing these cards in Indian history was Sheopur. Cards were usually made in the popular style of Bazar Kalam. On the other hand, in Sawantwadi, Maharashtra cards were made in Darbar Kalam or court style. These court-styled cards had dasvatara designs from Indian culture. The cards made in this style were usually thin, pliable, brightly colored, and consisted of rapid brush strokes in designs. The dasavatara Ganjifa style is considered to have been probably adapted in the 17th century as a response to suit the demands of the Hindu community. However, some of the iconographies remained similar to the Mughal cards. In Kashmir, the papier mache work was unique to the cards and the shape of the taj design on the cards is a unique feature of this region in the Indian culture.

EUROPEAN INFLUENCE ON INDIAN PLAYING CARDS.

While the larger room of debate suggests that the playing cards originated in South Asia and then traveled to Europe. There, however, is no doubt that during later centuries, Indian culture modified the card games and playing card designs according to European standards. The British soldiers took standardized designs on the playing cards from France to England to play during Christmas. In Sawantawadi, Maharashtra Indo-french-suited card box was manufactured with Ganjifa cards painted traditionally but containing the standardized French designs of Spades painted in black, hearts in red, diamonds, and clubs in white. The deck of cards used in card games became a status symbol during the colonial period in Indian history. As a result, the rich and elite in Indian society started demanding cards with European suit symbols that remained illustrated and produced locally. From the 16th century, Portuguese influence was evident in the playing cards of Indian culture. Designs such as cups, coins, swords, and clubs were copied and reproduced mainly in the states of Rajasthan and Deccan.

British influence however came later probably in the 18th century. Card packs of 52 and 32 were printed in local style. Adaptation of symbols could be best seen in Maharashtra where the traditional designs of cards used in card games were changed according to European standards. The horseman of the traditional Indian card became a Jack in the Europeanised version. In Orissa, the Dasavtara designs of cards were modified according to European format where Rama became the King, Lakshman became the Queen and Hanuman became the Jack on the Card. Another reason for the popularity of printed European cards in Indian culture was the widespread prevalence of Western card games such as poker, Rummy, and Bridge. The 32-card pack was introduced to meet the requirement of the game Piquet. Since Ganjifa cards could not be used for these card games, they were out-fashioned. It was however not the case that card games were not prevalent in Indian culture. Trick taking game of Ganjifa like the bridge was quite popular in Indian history and involved strict rules instructing the cards that may be led. A version of this game is still played in Orissa.

One of the favorite pass time of Indian men remains playing cards. Often daily wage labourers, itinerant workers take a rest from work in the afternoon to play cards. Popular places to play cards in the public are roadside, parks, and plinth or ‘chabutra’ in front of the shops .

Picture Courtesy : istock

Another popular card game was Naqsh. It was a gambling game like Blackjack, however, the target was 17 instead of 21. Special packs of forty-eight cards were produced in Bishnupur for the Naqsh card game. However, the Europeans created an image where Western games were seen as a status symbol of being a Sahib. The cardrooms or casinos as we know became the place of social gatherings for the wealthy. As a result, the wealthier class turned away from traditional Indian playing cards and card games. Gambling in India, however, is a state subject and the Public Gaming Act of 1867 is a central law that Prohibits one from being in charge of a Public gaming house or casinos. In 1955, Gambling was the most reported crime in the Connaught Place area of Delhi. The FIR reports details of lying stake money and playing cards left on the crime scenes.

By the 20th century, the handcrafted Ganjifa playing cards were overtaken by the printed European standardized cards. Turnhout in Belgium became the center of printed card manufacture globally during the 19th-20th century. Indian subcontinent became a significant market for these playing cards and as a result, a factory was established in Calcutta in 1922 by V.Genechten (the most famous cardmaker of that time) known as the Kamala Soap Factory which printed the Dilkhus playing cards and produced cards until the 1930s for clients all over the world.

Cards game and playing cards have been pivotal in women’s lives as well. Much of the literature of Indian history produced during the 19th c talks about the Westernization of Bengali women. The writings threatened the modernization of Bengali women who were allegedly imitating the idea of being a ‘Memsaheb.’ Bhudev Mukhopadhyay’s ‘Paribarik Prabanda’ published in 1882 describes the characteristics of an Indian woman being modernized, these included “reading books and playing cards.” Cards symbolized leisure for women but were considered an “expensive” way of social life. In reality, Cards game and playing cards in the afternoon became a refugee for women in Indian culture, who were stereotyped into following the distinction of public vs private spaces. Indian women were traditionally trained to be restricted to their households. Hence, leaving them no option for outdoor recreation activities. Many of the Indian nautches and prostitutes also used to play card games as a leisure activity and also as a deliberate attempt to enhance social standing.

In the famous movie Charulata (1964) directed by Satyajit Ray, the protagonist is shown playing cards on a summer afternoon to pass time.

An example of both cases can be found in popular culture. Satyajit Ray’s classic masterpiece Charulata (1964) depicts a game of cards between two women. On the other hand, a recent example of the latter case can be seen in the movie Gangubai Kathiawadi (2022), where the protagonist is seen carrying and playing cards (cards game). Thus, one can agree that the history of card games and playing cards in Indian culture has been interwoven in the Interplay of culture and foreign influences and the craze of card games just doesn’t seem to stop! Today online platforms provide various card games to which people are hooked, such as Solitaire and online Rummy. Recently, Mattel, a toy and game-sharing company announced the vacancy for the job of a chief UNO player in their office, whose priority would be to promote card games. It seems that the craze for cards and card games is just going to shoot up more in the coming year!

REFERENCES

- Mackenzie, and I. Finkel, (2004). Asian games: the art of contest. 1st ed. New York: Asia Society.

- N. Chopra, (1952) ‘GAMES, SPORTS, AND OTHER AMUSEMENTS DURING MUGHAL TIMES’, Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, 15pp. pp. 268-273. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/45436494

Beveridge, Annette Susannah (1922). The Babur-nama in English (Memoirs of Babur). Vol. 2. London: Luzac.

- May 15, 2024

- 6 Min Read