Hospitality on the Road: Exploring Travelers and Caravan Sarais in History

- EIH User

- July 19, 2023

For tourists today, options for accommodation abound. There are hotels, motels, online booking platforms like Trivago, and options for personalized stays through Airbnb. But where would travellers in the 17th century go when looking for sanctuary, a place to rest, refuel and recharge on their terribly long journeys?

The existence of elaborate networks of trade routes, especially during the 16th to 18th century is well known within Indian history. Road communications were crucial: goods had to be moved by merchants, the royals themselves travelled frequently, and huge armies might need to be moved to counter an invasion at any time. Along these routes, a vital institution emerged, providing crucial support, hospitality and respite to travellers and merchants alike: the Caravan Serai. The concept of institutions set up with the purpose of providing respite to weary travellers is not unique to the medieval era, or specific to the caravan serai. Dharamshalas, sattras, chavadi, for travellers and pilgrims have populated roadways since the ancient era. This article aims to shed light on the medieval-era caravan serais in the subcontinent.

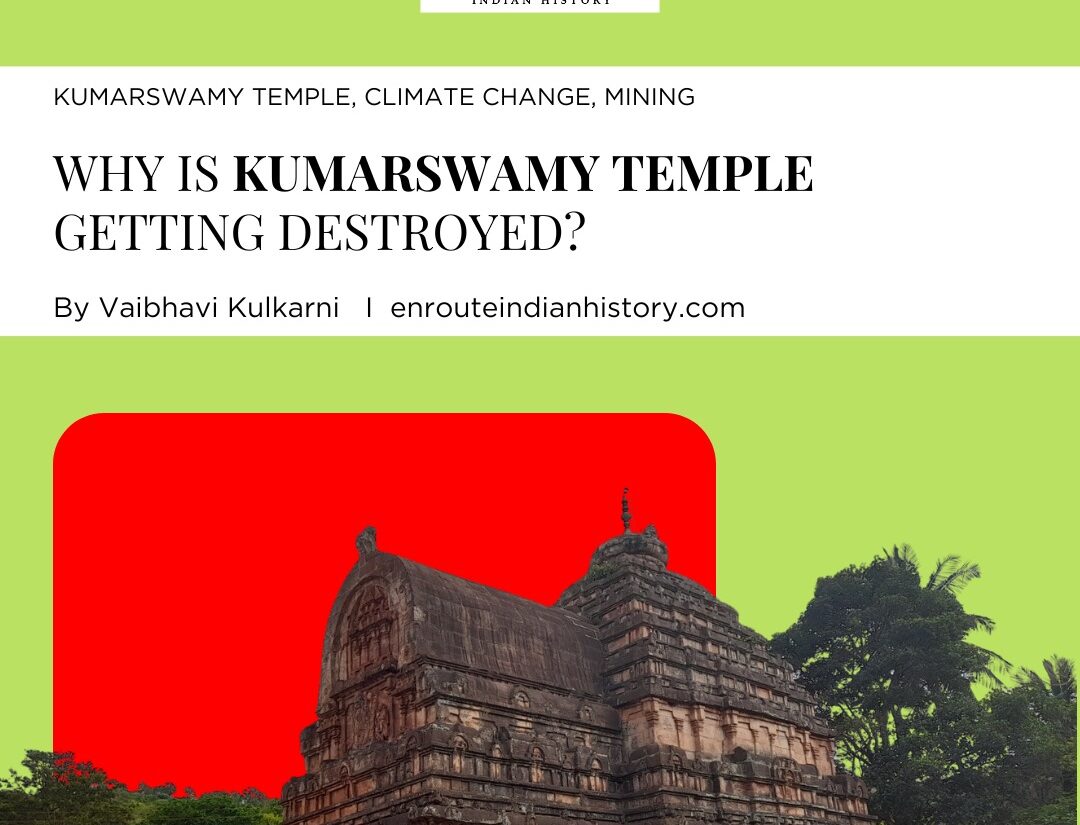

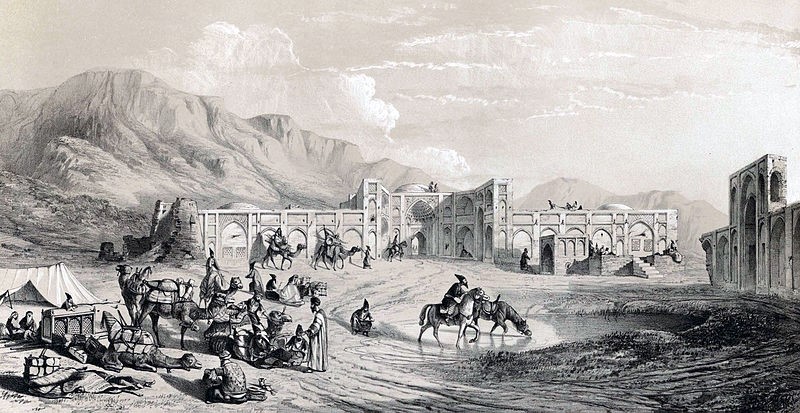

Figure 1 Caravan Serai in Central Asia by Eugène Flandin. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Caravan serais were roadside inns, serving as rest stops or waystations for travellers who traversed the vast subcontinent. People would arrive with their animals and caravans to find a hospitable venue in the sarais, which had small rooms for people to rest during the night. Sarais also had mosques for lodgers to say their prayers in, along with hammams and food and drink provisions for the travellers. According to Nicola Manucci, one caravan sarai had the capacity to host about 800 to 1,000 persons, with some being even larger. The structure itself was most often uniformly square in design and built around a large open courtyard. Serais were not only sites where travellers found rest, but also an opportunity to meet and interact with people from diverse regions—offering opportunities for exchange of material culture, language, traditions, and ideas.

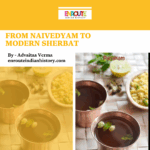

Sher Shah Sur is credited with initiating the large-scale institutionalized construction of Sarais, evidence for which comes to us from the Waqiat-i Mushtaqi (1580 AD). The construction of sarais was revitalized by the Mughals, and it was aimed that one sarai be located at every 10 kos, equivalent to what caravans could traverse in one day. The Persian text Chahar Gulshan (1750 AD) lists a large number of sarais falling between villages, towns, and cities. Two routes where sarais were prominent were the Grand Trunk Road, connecting the Indian subcontinent to Central Asia (covering cities of Calcutta, Delhi, Agra, Lahore, Peshawar and Kabul), and the route toward the Deccan, which passed through Malwa and the fort city capital of Mandu. Thus, a great number of sarais are located in Malwa, a region that witnessed great flows of commerce due to its position in the route toward the Deccan, and in the route to the port city of Surat.

Figure 2 Caravan Sarai at Mandu. Source: ASI

The sarais were built on the orders of the Emperor, but were also often constructed by princes, princesses, by imperial officers, or philanthropists. Fazl’s Akbarnama tells us that Akbar raised funds for the collection of several public works, including caravan sarais in 1586-1587. Jahangir as well, ordered jagirdars and officials of the Khalisa (territoris reserved for the imperial treasury) to build public works, also including sarais. These constructions were also aimed to incentivize people to settle in areas that were erstwhile deserted. Nur Jahan is also credited with constructing sarais, most famously the Badhashi Sarai for travellers’ use. Even princesses, such as the Princess Jahan Ara, the eldest daughter of Shah Jahan erected a sarai in Chandni Chowk, Delhi. Sarais, although popularised by rulers of the Delhi Sultanate and the Mughals, should not be thought of as an Islamic institution. Sarais such as Sarai Badridas, Sarai Malukchand, and Sarai Balchand suggest that Jains, as part of charitable endeavours were also engaged in the construction of sarais.

Once constructed, the serais were responsible for providing employment to a wide range of people. The chief official of a sarai was the shahna or Shiqdar. The shahna or shiqdar derived his sustenance from the land grants reserved for maintenance of the sarais, and was also in charge of ensuring consistently available supplies, and proper distribution of meals to the travellers and fodder for their animals. A caravan sarai was almost always accompanied by a market, and the shahna or shiqdar was also responsible for managing these markets. The shahna or shiqdar was further assisted by a service staff of cooks, watch-men, gate-keepers, darba (water-carriers), and cleaners.

Travellers’ Testimonies

Several travellers documented their impressions of the sarais. William Finch, an English traveller, in the 1620s described the sarai of Chaparghat as one of the most beautiful: “’Here is one of the fairest saraies in India, like a goodly castle then a inne to lodge strangers; the lodgings very faire of stone” (Early Travels in India, p.179). The English traveller Peter Mundy also described the structure of the sarai as having four towers, with four gates surrounded by a very high boundary wall and accompanied by battlements. The battlements are evidence of the measures taken to protect the travellers, their goods, and animals from bandits and thieves.

Francois Bernier (1620-1688 AD), a French physician who resided in India for twelve years generally held a negative view of the sarais in India. However, he was much impressed by the sarai built by Princess Jahan Ara in Delhi. He wished that a similar inn would be built in Paris for providing a safe haven to the travellers. He wrote that the sarai was in “the form of a large square with arcades, like our Place Royale”, the arches were separated by partitions.

In 1867, the colonial government passed the Indian Sarais Act to regulate the functions of these establishments. Interestingly, this law is still in force today and is the reason hotels in India are compelled to provide free water and washrooms to anyone who visits. While the era of sarais has passed, their influence on urban culture and the hospitality industry endures. Most sarais themselves have fallen into disarray today, a mere shadow of the grand establishments they once were. They lack recognition as heritage sites, and the theft of bricks from these structures is reported to be a common sight. Several of these had become common places of residence for those migrating during the Partition.

These roadside inns, with their grand architecture and practical amenities, served as vital waystations for travellers, fostering commerce and cultural exchange. The frequency with which the sarais feature in the descriptions provided by various travellers, highlight just how prominent they were at one point in Indian history. Caravan sarais, ranging from the impressive structures with towers and battlements to the more humble thatched huts enclosed within walls, attest to a thriving urban culture and mobility in the era.

References

Hasan, S. Bashir. “ROUTES AND TRADE IN MALWA UNDER THE MUGHALS.” In Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, vol. 57, pp. 347-360. Indian History Congress, 1996.

Kumar, Ravindra. “Administration of the Sarais in Mughal India.” In Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, vol. 39, pp. 464-472. Indian History Congress, 1978.

Anjum, Nazer Aziz. “” SARAIS” IN MUGHAL INDIA.” In Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, vol. 71, pp. 358-364. Indian History Congress, 2010.

Parihar, Subhash. “The Mughal Sarai at Doraha—Architectural Study.” East and West 37, no. 1/4 (1987): 309-325.

Parveen, Sagufta, and Mohd Noorain Khan. “SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC ROLE OF SARAIS (INNS) IN MEDIEVAL INDIA WITH ESPECIAL REFERENCE OF EUROPEAN TRAVELERS’ACCOUNTS.”

The Economic Times. “Sarai Amanat Khan: Mughal Era Caravan Sarai.” https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/magazines/travel/sarai-amanat-khan-mughal-era-caravan-sarai/articleshow/3081141.cms?from=mdr

- May 15, 2024

- 6 Min Read