“Bhagavan ke ghar der hai, andher nahi hai” (there is delay but not denial of justice in the court of the Lord), and “Upar wale ki laathi me aawaz nahi hoti” (the justice of the Lord is swift and silent) are some of the popular sayings in Northern India, used in common parlance in the context of the divine justice and its final say in the matters of this world and the next. Similarly, evocation of god in the realm of justice, legality, and punishment is an ancient tradition of the country, where the gods are often called outside their sanctums to partake in the worldly events of their devotees. Usually, they become the final authority or judge who keeps the records of the deeds of every being and serves them their sentences, in life and death. But in a few, rare and interesting cases, God becomes not the judge and jury, but the defendant and plaintiff, standing in the modern court of law, bringing the religious and the secular worlds face to face, in an intriguing correspondence.

Ram Lalla: The Young God of Ayodhya and one of the Parties in the Rama Janmabhoomi Case (Source: Times of India)

The History of God Living Among Humans

The Hindu Dharma shastras, repositories of legal knowledge, sometimes talk about the rights of the deity in the context of their property. A related idea of personification and personhood of the idol comes from the Shilpashastra (texts on Hindu iconography) which discuss the ritual of Praan-pratishtha of the idol of the sanctum sanctorum, in which the metal or stone statue is ritually consecrated to bring the divine essence within it (Lubin 2010). Additionally, the concept of the presence of divinity also received philosophical impetus from the traditions of Bhakti or devotion, which is based around a personal connection with the Lord, through acts of service or Seva in which the deity is not merely an idol but a living and active presence in the world. During the early medieval India, with dynasties making land grants and pompous donations to religious centers, temple towns developed especially in Southern India, with the deity of the sanctum becoming the Lord or Swami of the town.

However, there always remained a difference between the religious and philosophical idea of the deity as an active, living presence and their rights over the property. Brahmanas, ritual experts and priests were assigned by the donor or patron of the sacred centers to look after the property and treasures of the temple on the behalf of the deity.

The system continued under the Sultanate and Mughal period, but things were about to change with the advent of the British. Guided by their concept of God and property, along with modern jurisprudence and law, the British made the first clear attempt to concretize the idea of deity not in a religious, but in a legal sense, as a “legal entity” or “juristic person” (Govind 2021).

God as a Legal Entity

Beginning to administer justice in a unique cultural context of the Indian subcontinent, especially its religious structures, the British government often faced issues with the vagueness of the definition of God as the owner of the temple property (Shrivastava and Tiwari 2021). Compiling the incomprehensible rich legal traditions of Hinduism as Hindu Law, as a “solution” to the British officials and lawmakers perceived as the inability of the caretakers of the property, God was defined as a legal person, as opposed to a natural person (e.g. humans). The deity (worshipped image) of temple as a juristic person could now become a plaintiff in cases, exercising their powers from the physical icon of the sanctum (M. n.d.), only after the Pran-pratishtha ceremony (Lubin 2010). Repeating the remarks of Medhatithi, an ancient authority on law, “Hindu Law” gave the deity legal rights in a limited manner, subject to contextual interpretation, leaving enough room for discourses within and outside the courtroom, an elasticity which would go on to open Pandora’s box in the legal and social arena of modern India.

Deity as a Plaintiff and Person

When one begins the discussion on a deity in the courtroom, the latest and the most popular case that comes to mind is that of Ayodhya, where Ram Lalla Virajman was one of the interested persons, who recently won the case and “returned” home. There however are many more cases of God gracing the court, each one of which is as interesting as a fiction novella. Let us take a closer peek into a few of these cases, and understand the presence of God in the field of law in relation to – a) cases of Act of God, b) God as a Legal Person, c) God as a Plaintiff. But first, let us turn towards the example of the 2012 Bollywood drama-comedy, “OMG”, starring Paresh Rawal as a small businessman and Akshay Kumar as “Krishna Vasudeva”.

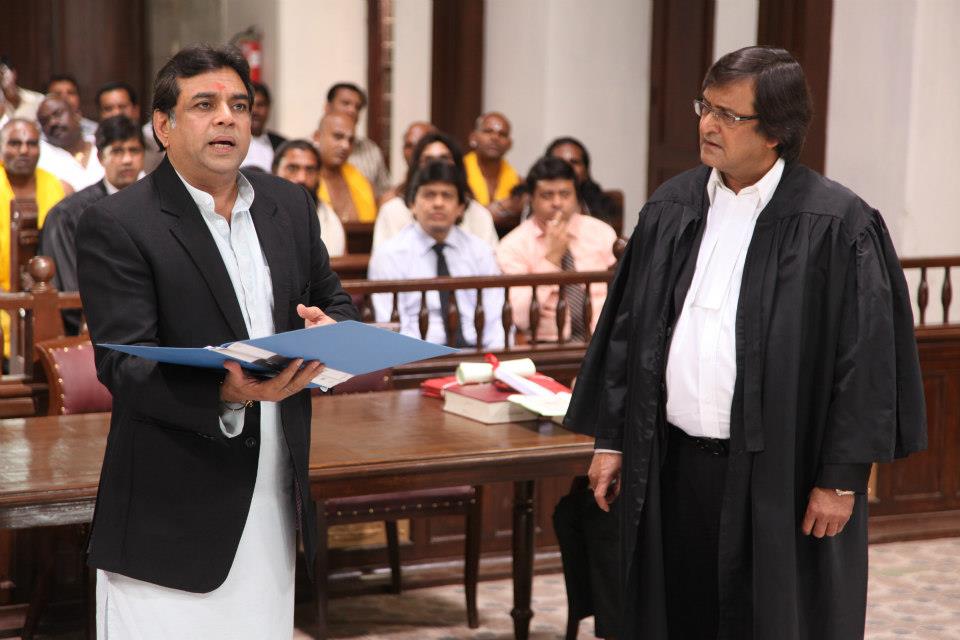

Paresh Rawal as Kanji Mehta fighting his case against God, a scene from OMG (2012) (Source: The Common Man Speaks)

The movie “OMG” or Oh My God revolves around Paresh Rawal as Kanji Mehta, whose life is turned upside down due to an earthquake which left his shop in a dilapidated state. Seeking a compensation for his loss, Mehta is informed by the insurance company that they are not liable to pay him because the destruction was an “act of God”. A helpless but determined Mehta approaches the court with a complaint against “Bhagwan” or God, leading to series of dramatic episodes mixed with an element of comedy and social commentary on the religious beliefs and misbeliefs of the country. In real life however, one cannot simply blame God for a major loss caused by natural forces. The legal concept of “Act of God” is evoked and applicable on cases where forces of nature caused loss of life or property which could not have been foreseen in any manner. The assessment of whether the case is one that involves an act of God depends upon the judgement of the courts, and do not require God to materialize as a “person.”

God’s Right to Privacy

Male Devotees Performing Worship in the Sabarimala Temple (Source: Economic Times)

So, when and how does God, an omnipresent being becomes a person, as per Indian law? To understand this, we will now go on a pilgrimage to the home of Ayyappa (a South Indian Hindu deity, born from Vishnu and Shiva), in Sabarimala, but with caution, because if you happen to be a menstruating woman, thou shall not enter! Welcoming all irrespective of their religion and caste (Acevedo 2023), the sanctum of Sabarimala is closed to young women, who are seen as a deterrence in the vow of celibacy taken by Lord Ayyappa. People approaching the court on the behalf of Ayyappa, remarked that under the Article 25 of the Indian Constitution, Ayyappa, like any other “person” had the right to observe his religious freedom and under Article 21, had “a right to privacy” (Acevedo 2023, 459). What the parties on the part of Ayyappa were asking, was a Constitutional right for the deity, as any other citizen of the country. The case continues to be legal and public sphere, but one thing the court clarified was that though Ayyappa was a legal entity, that too in a limited sense, and had a right to be worshipped in accordance to his ritual preferences, he had no Constitutional rights. The case of Sabarimala and the dispute over assigning citizenship to the deity (which makes him a person) has its root in the ancient culture of the country, especially in Uttara and Purvamimansa, a component of the Vedanta literature. According to the Uttara Mimansa, deities are seen as living beings, while the Purvamimansa underlines that deities are imaginary presences, made for sacred rituals (Acevedo 2023, 461).

God as Property Owner

The definition of personality and characteristic of the deity in legal context become complicated yet, when one considered the religious belief that one God can exist at a single point in time, in many forms. In the works of Donald R. Davis, the case of Pathur Nataraja, travelling from a humble sanctum of Tamil Nadu, the international black market and making a celebrity’s return, after making a stop in the court of Britian. The Union of India approached the court for returning the bronze to its home, with a little assistance from another plaintiff, Shiva himself. Shiva, residing in the Thanjavur shrine as a Lingam extended a claim over the Nataraja bronze, since it was his property, one of the many aspects of the deity. Victorious, Shiva was declared the rightful owner of his form as Nataraja, making the Pathur Nataraja case a notable mention in the fascinating history of divinity materializing into a person in the court of law.

Is a Legal Definition of God Possible?

The term “person,” which is often used in the addition to “legal”, to define God in cases of Hindu law, is itself an ambiguous term, undefined by the Constitution of India. The religious tradition- Hinduism, in the background of which the process of defining “God” (when they enter the court) has begun, remains a non-homogenous element, which is populated by contrasting, conflicting and contradicting components. As one moves further, towards the philosophical and spiritual meanings of the religion and God, sayings like “Kan-kan me hain Ram base” (Ram resides in each particle of the Universe), welcome you, adding to the existing mystification.

Today, with the report of the Archeological Survey of India on the Gyanvapi mosque complex, making claims for the presence of an earlier temple complex at the site, is once again trending on social media debates and legal discourse and is adding fuel to the fire of communalism, and the previous cases of legal personhood of God remain unclear at best, a question worth asking is “If Ram (god) resides in every particle, where does his property, presence and control begin and end, and what will be implications of the attempts to define god and his territory in the context of Hinduism, a religion that tends to metamorphosis in every century?

References

Acevedo, Deepa Das. 2023. “Deities’ Rights?” Journal of Law and Religion 450-468.

Govind, Rahul. 2021. “On The Deity as Juristic Personality: The Religious, The Secular And the Nation in The Ayodhya Dispute And the Ayodhya Judgments (2010 and 2019).” National Law School of India Review .

Lubin, Timothy Davis Jr. Donald R, Krishnan. Jayanth K. 2010. Hinduism and Law: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press.

M., Umamageswari. n.d. Legal Service India. https://www.legalserviceindia.com/legal/article-1199-rights-of-a-deity.html#:~:text=No%20fundamental%20or%20constitutional%20rights&text=To%20conclude%2C%20it%20can%20be,only%20after%20its%20public%20consecration.

Shrivastava, Anujay, and Yashowardhan Tiwari. 2021. “UNDERSTANDING THE MISUNDERSTOOD: MAPPING THE SCOPE OF A DEITY’S RIGHTS IN INDIA.” International Journal of Law and Policy Review (IJLPR).

Image Courtesy

- Paresh Rawal as Kanji Mehta fighting his case against God, a scene from OMG (2012) (Source: The Common Man Speaks)

https://thecommonmanspeaks.com/oh-my-god-review/

- Male Devotees Performing Worship at Sabarimala Temple

- Ram Lalla: The Young God of Ayodhya and one of the parties in Ram Janmabhoomi Case https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/travel/travel-news/the-white-marble-idol-of-ram-lalla-that-couldnt-make-it-to-the-main-temple/articleshow/107103267.cms

- September 27, 2024

- 9 Min Read

- May 15, 2024

- 6 Min Read