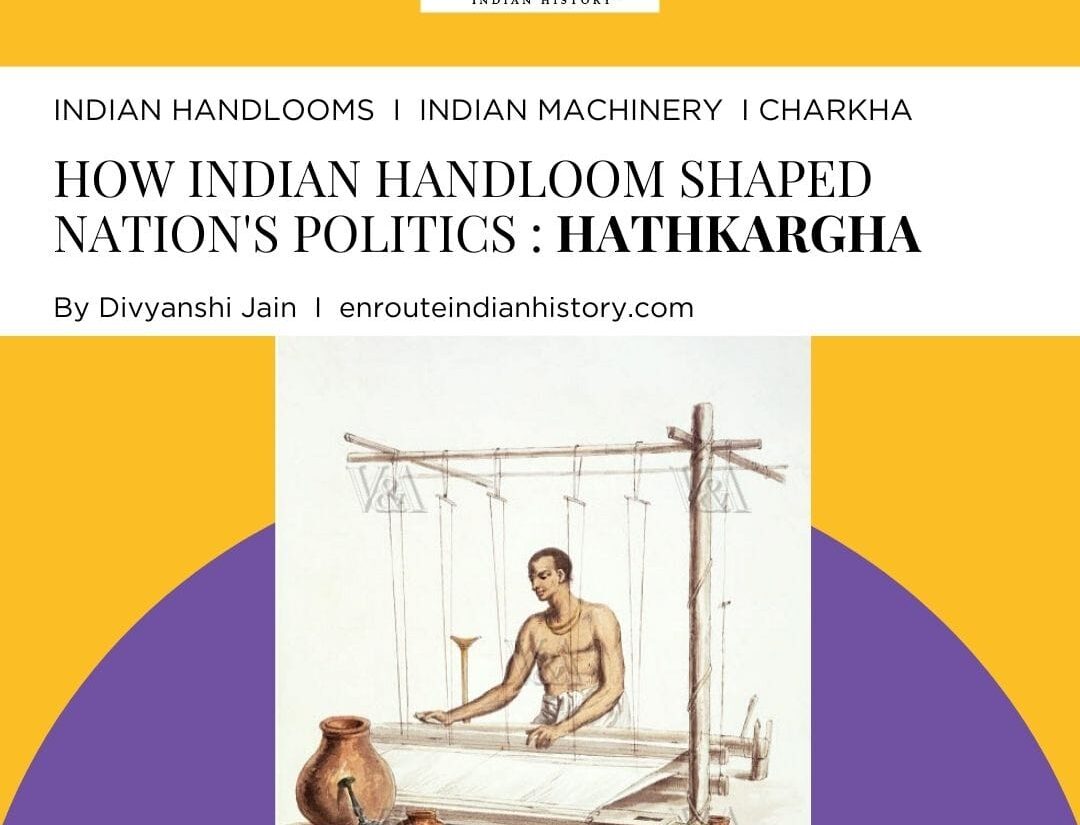

Khadi, now experiencing a resurgence in the fashion scene, is not just a trend but a testament to endurance and resilience. Beyond its current allure for its eco-friendly and versatile attributes, Khadi carries a storied past of perseverance and rivalry. Over a century ago, it stood tall as a cornerstone of the Indian national movement, earning the title of the fabric of Indian independence. Its significance lay not just in its practical qualities but in its symbolic essence, serving as a potent symbol of defiance and a catalyst for transformation. Khadi refers to a handspun and handwoven fabric made primarily of cotton, though it can also be woven from silk or wool. Behind this organic fabric lies an indigenous machine which is simple, efficient and does not snatch away work from weavers. This machine is the handloom or the hathkargha.

“Hathkargha” refers to the art of hand-weaving in India, a craft deeply ingrained in the country’s cultural and historical heritage.

Indian handloom has gained global recognition for its craftsmanship, intricate designs, and high-quality fabrics. The demand for handwoven textiles, sarees, fabrics, and garments has increased internationally due to their uniqueness, cultural significance, and skilled artistry. Despite its rich heritage, the handloom industry faces challenges in the modern era. Competition from power looms, lack of infrastructure, fluctuating market demands, and sometimes inadequate support for artisans continue to pose challenges to the sustainability of traditional handloom practices.

Indian handloom has ancient roots. Evidence suggests that the art of weaving existed in the Indus Valley Civilisation. Archaeological findings, including remnants of spindle whorls and loom weights, suggest the existence of a well-developed weaving tradition during this era. Over centuries, different regions in India contributed to the development of handloom textiles. Weavers handspun and produced handwoven cloth in various forms. From Bandhini and patola from Gujarat and Rajasthan, Bengali Muslin, Sambalpuri from Odisha to Kanchipuram silk saree from Tamil Nadu, every region contributed unique styles to this rich tapestry of weaving.

A Weaver, by William Orme (1797-1819). Watercolour. India, c.1801-04. Source- Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Plate 16 of Charles D’Oyly’s “Antiquities of Dacca”, 19th century , Source- The British Library Online Gallery

With industrialisation, power loom gained prominence. Edmund Cartwright invented the first power loom in 1785. In 1904, Late Vitthalrao Datar set up the first Indian power loom at Ichalkaranji also known as the Manchester of Maharashtra. But even before the setting up of the Indian power loom, Indian markets were flooded with affordable, mass-manufactured textiles and clothes produced in the European power looms. This took a toll on the traditional weaving industry of India.

What Dadabhai Naoroji termed as ‘Deindustrialisation’, can be well understood in the light of decline of the booming handloom industry. There was a systematic extermination of the Indian weaving industry by machine-made goods and skewed colonial policies. The spinning wheel and handloom (hathkargha) were once the backbone of a significant number of artists’ livelihoods. With livelihoods snatched, unemployment and poverty increased among them. This became a cause for resistance to Britishers and colonial rule. Nationalist leaders upheld this as a main objective in the Swadeshi movement.

Weaver on handloom, 20th century

Weaving on handlooms, c. 1913

Launched as part of India’s struggle for independence from British colonial rule, the Swadeshi Movement had a profound impact on the handloom industry. It aimed at promoting indigenous goods and boycotting British-made products to assert economic self-sufficiency and national pride. The Swadeshi Movement encouraged Indians to prioritize the use of domestically produced goods over British-manufactured products. This included advocating for the use of handcrafted Indian textiles, particularly khadi (handspun and handwoven cloth), as a symbol of self-reliance and national identity.

Khadi was more than just a fabric; it represented a way of life. It was seen as a rejection of opulence and a return to the simplicity and dignity of rural life. It symbolized the idea of self-sufficiency and self-respect. Khadi became a unifying symbol for Indians across different socio-economic backgrounds. It represented the ethos of simplicity, self-reliance, and unity among diverse communities in the fight against colonialism. Wearing Khadi became a political statement against British rule. Leaders of the Indian National Congress and freedom fighters adopted Khadi as a sign of their commitment to the cause of independence and as a rejection of foreign-made goods. This struggle is remembered to this date.

National Handloom Day in India commemorates the Swadeshi Movement launched in 1905 on August 7th, which aimed to revive the country’s indigenous industries, including the handloom sector, and promote the use of locally made products. National Handloom Day serves as a reminder of the historic significance of India’s handloom industry and its role in the country’s cultural and economic development. It promotes the idea of “handmade in India,” encouraging the appreciation and patronage of handcrafted textiles, supporting artisans, and fostering the growth of this ancient craft.

Handloom Weaving stamp – 1980

Just like the National Handloom Day, the Handloom Weaving stamp of 1980 signifies the importance of the weaver and the simple machine used in the process of weaving- the hathkargha. At a time when mass communication was not prevalent and had few sources, the postal system was used by many. Thus, symbolic stamps became an instrument of promoting information and awareness amazon the masses.

While a century back, Gandhi ji and his advocacy for charkha and khadi gained momentum in his satyagrahas, his ideals of non-violence or ahimsa, and his ideal to promote the dignity of labour left a legacy. Such is the case of Kaimagga Satyagraha. The Kaimagga Satyagraha was a peaceful demonstration initiated by Karnataka’s weavers and supported by those from Seemandhra in 2014. It has encompassed hunger strikes and Padayatras. The weavers are battling for their livelihood rights, presenting crucial demands to the State Government. Among these, a primary concern is the jeopardy faced by handloom weavers due to fabric adulteration. While the government offers perks like subsidized electricity to powerloom weavers, handloom weavers find themselves unsupported and devoid of benefits. Even their solitary source of electricity, a single lamp in their weaving sheds, remains unsponsored. This preference for incentivizing the powerloom industry spells trouble for the handloom sector, prompting the weavers’ central plea: DO NOT KILL HANDLOOM.

The story of Hathkargha, woven through the fabric of time, narrates a saga of resilience, struggle, and enduring heritage. From ancient origins rooted in the Indus Valley Civilization to the pivotal role in India’s freedom movement, handloom weaving stands as a testament to the country’s cultural legacy. The deindustrialization of handloom due to the rise of power looms brought about a decline, snatching livelihoods and cultural heritage from skilled artisans. Even today, the echoes of this historic struggle resonate. Instances like the Kaimagga Satyagraha in recent times highlight the ongoing battle for the rights and recognition of handloom weavers. In commemorating National Handloom Day and the legacy of Hathkargha, it’s imperative to safeguard this rich tradition. Preserving handloom isn’t just about protecting an industry; it’s about safeguarding cultural heritage, empowering artisans, and sustaining a legacy that weaves together India’s past, present, and future. It’s a call to cherish, protect, and nurture the fabric that binds India’s diverse threads into a vibrant tapestry of tradition and resilience.

References –

- Desitrust. “Kaimagga Satyagraha: A Chronology.” The Sustainable Way of Life, 2 Mar. 2015, thesustainablewayoflife.wordpress.com/2015/03/02/kaimagga-satyagraha-a-chronology/.