Nestled in the lap of the mighty Brahmaputra, Salmora in Majuli, Assam, is home to an ancient and distinctive type of hand-made pottery that does not use the potter’s wheel. Salmora Pottery is one of the many cottage industries that have thrived in Majuli – the cultural capital of Assam for centuries. My earliest acquaintance with the potters of Majuli was through a conversation shared between my younger self and my grandmother. I was told that the earthen tekeli(s) (pots) used during Magh Bihu to make and store curd in my hometown of Lakhimpur, came from Majuli, located across the Subansiri River. It was only later that I would come to know of Majuli as the largest inhabited river island in the world. For as long as they can remember, the potters of Salmora have been seasonally selling their pots on the banks of the Brahmaputra from Sadiya to Dhuburi and across the Subansiri on their boats. However, this age-old industry is facing major challenges in recent decades.

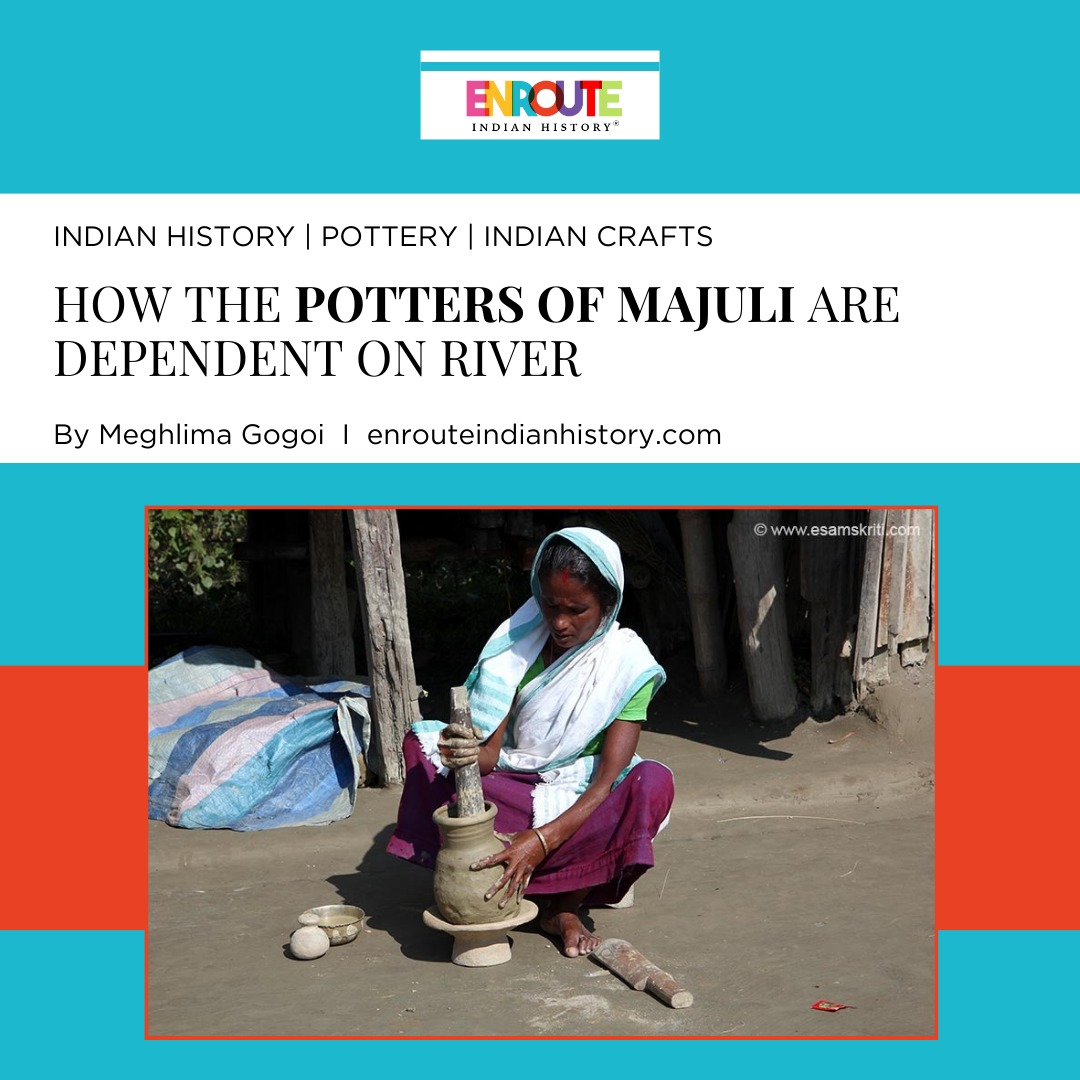

A woman shapes the pots using an aphori (Source: Nezine: Bridging the Gap)

What makes Salmora pottery unique?

Pottery is an integral part of Assamese society, serving ritualistic and utilitarian purposes. Pots come in different shapes, sizes, and functionalities like koloh, tekeli, mola charu, dunori, xarai, etc. These wares are essential in marriages, pujas, and festivals apart from being used for storing water, making curd, fermenting rice beer, etc. The centrality of pottery to the Assamese society can also be gauged from the wide range of idioms and phrases that employ references to pottery. Different forms of handmade pottery have co-existed in Assam, the Salmora pottery being one.

Implements used by the potters of Salmora (Source: Nezine: Bridging the Gap)

The men dig 60 to 70-foot-deep wells on the banks of the Brahmaputra to extract a glutinous clay called lodha mati. It is stored in the house and softened by mixing with water as and when required. The clay is mixed with sand and kneaded to attain the right combination of hardness and flexibility. The actual shaping of the pots is a woman’s job. The clay dough is placed upon a flat earthen board (pat) and shaped using a wooden plate (aphori). The outer surface is smoothened using a piece of wooden bat (pitun), a stone tool (bolia) of about 6–12 inches is used to hollow out the inner surface of the pot and a cloth (gorha kapur) is used to wipe off excess clay. While there is no use of a potter’s wheel, the women employ a unique technique of rotating the pat using their toes while simultaneously working on the pot with their hands, giving it symmetry. After the desired shape is achieved, the pots are sundried and then collectively baked in a driftwood-fired kiln called ‘poghali’ that can bake up to 1500 pots in one day.

The Potter Community

Only three villages – Barboka, Kamjan Elengi, and Besamorathat of the Salmora mouza (revenue circle) continue to produce pottery today. Salmora has a heterogeneous population of several communities like Kumar, Kaibarta, Kalita, Mishing, Jogi, Bania, Brahmin, Ahom, etc. Traditionally, it has been the Kumars who were engaged in pottery. It is said that they migrated from Sadiya during the Ahom Age in search of suitable clay. Women shaped the earthenwares while men contributed to the collection of clay, baking, and selling process. Generation after generation of women have acquired the craft from their mothers and grandmothers from a very young age. Draped in their hand-woven mekhela-sadors, the women spend 3 to 4 hours each day shaping clay from the river into a variety of objects.

Woman hollowing out the pot using a stone pounder (Source: eSamskriti)

The neatly stacked rows of pots lined along the elevated chang ghors (stilt houses) of Salmora offer a beautiful vista in the winter. But it is the monsoons that bring out the duality of their co-existence with the untamable Brahmaputra. On one hand, the clay that the river deposits on its banks sustains their livelihood. On the other hand, the chang ghors symbolize their perpetual struggle against the annual havoc wreaked by the flooding of the Brahmaputra. The floods prevent the manufacturing of pots for the entire monsoon season as in addition to their fields and pastures, the river banks that provide the clay, and the houses where they are dried and stored are submerged. An unrelenting question in the minds of these island dwellers is reflected in the hauntingly beautiful song ‘Majuli’ by Nilotpal Bora:

‘Barikhare godhuli, thakibo ne eibeli, nodi khoni mone mone xui?’

(Will the river sleep quietly in the evenings, this monsoon?)

Flooding in Salmora breaking through geo-bag embankments

(Source: Abhinav Sankar Goswami, DownToEarth)

Challenging times

Today, over 500 families of Salmora are dependent on pottery for their livelihood. But there is a sense of gloom that surrounds the future of this cottage industry. It is no longer profitable for the people of Salmora for many reasons. There is an exponentially higher demand for products made from materials like steel, aluminum, plastic, etc over earthenware. Even in industries like dairy, where earthenwares are in demand, the potters of Salmora are failing to acquire much profit due to the absence of a sound market, lack of formal sources of credit, and stiff competition from cheaper machine-made alternatives. The nature of the craft itself resists mechanization as it is the hand-made nature of the pots that make it unique. Younger generations are no longer keen to carry on the tradition as they have witnessed their parents toil away their entire lives for abysmally low profits. Even the older generations acknowledge that the legacy is on its end days. They would rather see their children move out of the ever-shrinking island in search of more rewarding avenues and break free of the cycle of poverty.

The final blow to the potters of Salmora has come in the form of the directive of the Brahmaputra Board banning digging on the banks of the Brahmaputra. The Board believes that the constant digging for clay on the riverbank weakens the embankments that are built to prevent soil erosion, resulting in massive erosion every monsoon. This accusation is up for debate, as other parts of Majuli that do not practise pottery are also witnessing rapid erosion. But the ban on the extraction of clay in their villages has had real consequences for the Salmora potters. The cost of production has significantly increased as they now need to buy clay from the market. The market-bought clay is not of the right consistency causing a decline in the quality of the pots. A new dilemma centered around the river has thus emerged for the people of Salmora.

Tourism: A new lease of life or An illusory consolation?

Majuli has witnessed a steady growth in the flow of tourists in recent years. Majuli has always been venerated as the center of Neo-Vaishnavite culture in Assamese society. But it is only with the improved connectivity in the last few years, that more and more people are making their way to experience its rich cultural heritage. Government promotion and global connectivity in the age of social media have also played their role in drawing tourists from outside Assam to the lush green heritage island. Organizations like ‘Root Bridge’ are carrying out cultural immersion initiatives in association with Assam Tourism Development Corporation conducting programs like ‘Majuli on Cycle’. Salmora has not remained isolated from this new development. People come to Salmora to witness the art of pot-making, and on lucky days get to see the firing process as well. Archaeologists and researchers fascinated with the pottery of Salmora, which bears resemblance to the Harappan pottery come to study the wares and the communities that make them.

Tourists in Salmora (Source: NorthEast Travelers)

However, given the fragile ecosystem of the island, it is pertinent that the tourism industry in the region is eco-friendly and sustainable. Only then, would it be able to bring lasting prosperity to the people of Majuli while allowing them to preserve their heritage. It is also important to ensure that the profits of tourism benefit the locals, rather than any outside agencies and corporations. There is a rising demand for eco-friendly products among high-end consumers in the global market. Finding the right market and streamlining production in that direction would increase the demand as well as income of the Salmora potters. Other traditional forms of pottery from the region like the Longpi pottery of Ukhrul, Manipur has been able to carve a niche for itself in the international market. The right combination of governmental support, local participation, and innovation has the potential to make this industry profitable again. But ultimately the river looms large. Unless more permanent solutions are found to the problem of erosion, the people of Salmora will continue to live in the shadow of an eventual doom.

REFERENCES

Regon, B.J., 2019. Problems and Prospects of Pottery Industry in Majuli. International Journal of Research in Engineering, Science and Management, 2(5), pp.952-955.

Devi, L., 2022. Traditional Pottery in Assam and its Role in Assamese Socio-cultural Life. Journal of Positive School Psychology, pp.4504-4507.

Neog, B.C., 2016. Majuli artisans keep ancient handmade pottery and centuries-old barter trade system alive. Nezine, Bridging the Gap