When we think of traveling today, one of the foremost things to do is to create a playlist for the journey with the most wonderful music. But this tradition of traveling music is not a new invention or a modern age phenomenon. It is in fact, a historical trend deeply entrenched in the Indian lifestyle as witnessed in the Tappa music of Punjab. This folk music mainly was sung by camel riders in the late medieval and early modern periods. Most of us have heard the famous Punjabi lyrics- “Baari Barsi Khatan Gaya Si, khat ke le aanda…”- which translates to ‘man had gone to work for 12 years and brought back something’, a phrase usually suffixed with some item one might bring back from a long journey. This folk music of Punjabi music is a historical treasure often overlooked for its modern versions. Folk music often depicts the socio-cultural life of its indigenous region giving us insights into the lives of normal people of past times, the information on whom is already rather scant. We must learn where this high-tempo and energetic traveling music came from, and what its effect on the Indian music scene has been.

FIG.1. CAMEL RIDER FROM PUNJAB

https://en.rattibha.com/thread/1573529609601134592

ROOTS OF THE TAPPAS

Tappa essentially means ‘jump’ in Punjabi vernacular, and this nomenclature has a very unique origin. The story goes that the originator of Tappa music, Ghulam Nabi Shori, colloquially known as Shori Miyan, was traveling in Punjab when he heard the coarse and unhinged music of the local camel riders traveling between Afghanistan and Rajasthan at that time. This singing caught his ears, and he was amused by the jerks in the voices of camel riders combined with their coarse folk melodies. The jerking of the camels brought a natural non-rhythmic tempo in the voices of these camel riders, motivating the maestro to be creative and inventive. Shori Miyan, trained in the khayal form of singing from his father, Ghulam Rasool Khan, a court singer for Nawab Asafudollah of Lucknow in the 18th C, polished this music with his hereditary training in classical music leading to the evolution of the name Tappa for this genre of folk Indian music. He not only was inspired to learn the Punjabi after listening to the camel riders, but also added the embellishments of taan, zamzama, and khatka of classical Indian music.

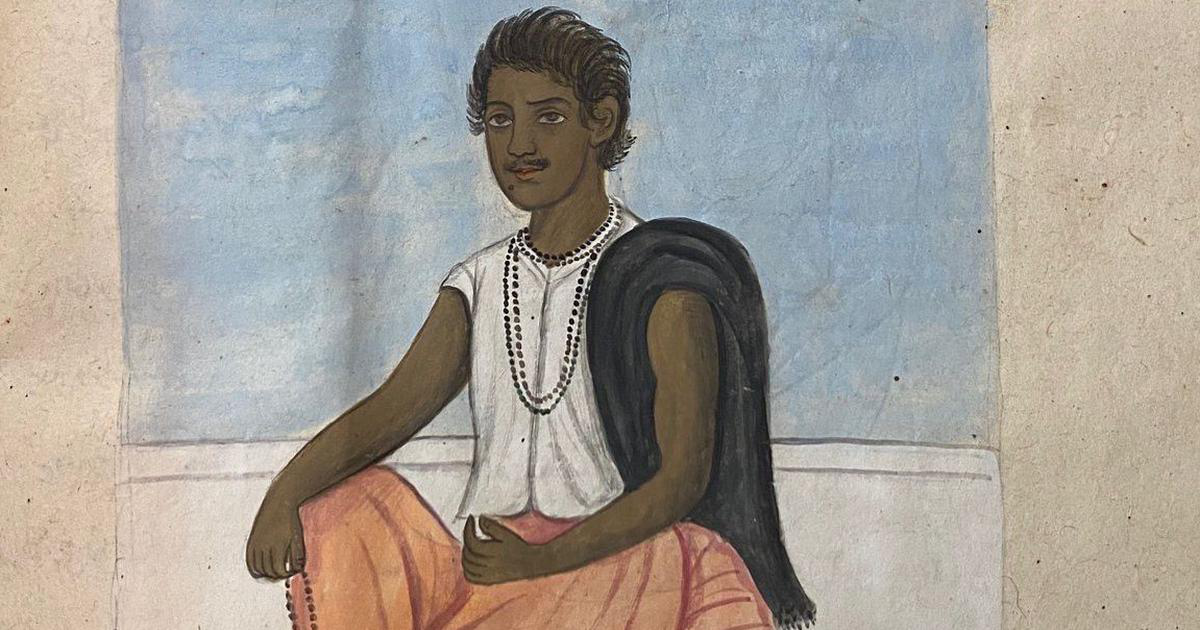

FIG. 2. A portrait of GHULAM NABI SHORI in the History of Lucknow by Husein Ali Kahn (c. 1826), Amherst College Archives and Special Collections.

https://scroll.in/magazine/1014226/how-a-music-form-inspired-by-the-songs-of-camel-drivers-of-punjab-sindh-became-popular-in-bengal

Tappa music’s unique features are its quips and witty wording coupled with short tanas of two to four lines that result in the best quick melodies sung on camel backs traditionally by journeying camel riders. This type of Indian music describes the romantic meeting of lovers combined with humorous and ironic recreations of the most beautiful folk music. Slowly and steadily, the policed version of Shori Miyan’s version of Tappa gained prevalence in the 18th century and was passed down through generations of hereditary musicians who subscribed to this specific form of Indian music. However, in the 16th century in a Braj Bhasha book “Chaurasi Vashnavan ki Varta” by Shree Gokul Nath Ji, there is a mention of nautch girls dancing on Tappas and Khayal music in the market at Agra. There is also evidence of this Indian music style existing in the 17th century as mentioned in the Persian work “Rag Darpan” of musicologist Faqirullah as a popular form of romantic folk music in Punjab. His contemporary Mirza Khan mentions a similar kind of music named Dapa, which is not in Punjabi vernacular but shares characteristics of Tappa music.

Due to scant and scattered materials, it has been difficult to trace the historical lineages of this Indian music style other than common knowledge of its inspiration, inventor, and geographical context. Nonetheless, it is widely known that the classical Indian music version of the Tappa songs was first well preserved and reproduced in the Kasur-Patiala gharanas by trained musical maestros. The Kasur gharana was patronized by the first Sikh ruler of modern Punjab Maharaja Ranjit Singh and later merged with the Patiala gharana to become the Kasur-Patiala gharana of Indian Music at Lahore. There is also evidence of this folk music being patronized at the court of Mughal Emperor Muhammad Shah who was also known as ‘Muhammad Shah Rangeela’ in the 18th century for giving into the pleasures of life through the known works of court musicians and Hindustani music maestros Sadarang and Adarang who are known to have sung Tappa music for the Mughal ruler.

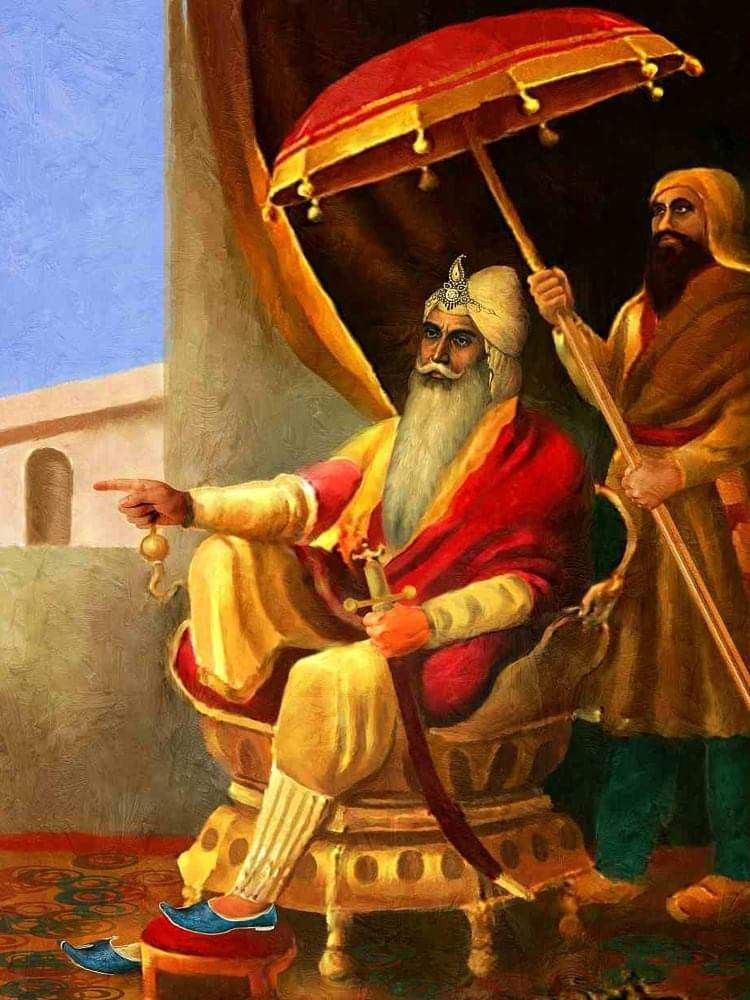

FIG.3 MAHARAJA RANJIT SINGH OF PUNJAB

https://in.pinterest.com/pin/638737159630499515/

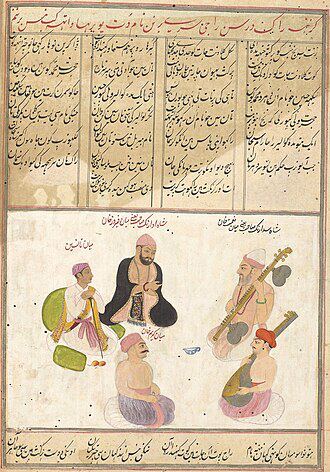

FIG.4 SADARANG is depicted in a Raagmaala miniature. University of Pennsylvania, U.S.A

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sadarang#/media/File:Sadarang,Descendant_of_Naubat_Khan.jpg

TRAVELLING TAPPAS AND TOPPAS

It is said that Shori Miyan eventually settled in Lucknow and trained other musicians in Tappa who then traveled to other regional courts beyond the Northwest frontier in the 18th-19th century. Although orientalists such as William Jones considered this folk music as rude only refined by the efforts of Shori Miyan, this style of Indian music persisted and traveled across the subcontinent till Bengal, creating gharanas and training musicians in the entire Gangetic plain. The contribution of Gwalior and Benaras gharanas into Tappa music is credited to this traveling of folk music from the northwest to the middle parts of India. Miyan Shadi Khan at the court of Raja Udit Narayan Singh of Benaras, as well as Mummi Khan and Hussain Khan of Lucknow, were such disciples in the erstwhile United Province area. Meanwhile, Haddu Khan, Hassu Khan, and Devajibuwa Tappewale belonged to the Gwalior gharana and became famous Malwai Tappa musicians of the time.

However, the most unique confluence of folk music occurred in Bengal when Tappa music reached its frontier through an individual colloquially called Nidhi Babu and formally known as Ramnidhi Gupta who from his employment at Chhapra in Bihar in the 18th century grew an affinity for this Indian Music style, learned it from a Hindustani maestro and took it home to Bengal with him to create an indigenous style of Bengali Tappa – Toppa – different from the Punjabi one. The fast pace was slowed and elongated in the Bengali version, and the romantic quips were exchanged for themes of love and tragedy, mainly dedicated to the concubine of a diwan in Murshidabad for which his compositions gained immense internal criticism. These compositions were considered indecent and obscene for women, and even Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyaya indirectly criticized these compositions in his work “Bishbriksha” attributing these to shameless women. However, there is evidence that Nidhi Babu not only composed love songs but also Brahma Sangeet on the two-sentenced quips of Toppa. One such song is ‘Parambrahma tatparatpar parameshvar/ Niravjan niramay nirbishese sadashay/ apna apni hetu bibhu bishvadhar’ (behag/ada).’ His disciples Kalipada Pathak, Ramkumar Chatterjee, and Kali “Mirza” who used to sing in both Bengali and Punjabi added to the dissemination of Toppa music in Bengal among the masses. Nidhi Babu’s verses were compiled in the volume ‘Geet Ratna Granth’ in 1837 to avoid misinterpretation and encourage their correct usage.

FIG.5. NIDHI BABU, THE INVENTOR OF BENGALI TOPPA

https://www.getbengal.com/details/bangla-tappa-born-from-banjara-music-popularized-by-nidhu-babu

Over time, Toppa became folk music adjacent to Bengal as it was carried to the masses by bardic traditions in the 19th century who gave it a theatrical nuance, such as Gopal Ude. But one of the most fascinating addendums in the evolution of Toppa is its adoption by Rabindranath Tagore in his music – Rabindra Sangeet. His tryst with Toppa music gave it a cinematic flair by adding emotional variation which was eventually utilized by the great director Satyajit Ray in his ‘Kanchenjunga’ in the song ‘E Porobash Robe Ke’ (Who will live in this Alien Land). One of his other compositions – ‘hala na hala na sai, hay/ marame marame lukano rahila, bala hala na‘- is another example of Toppa influence in Rabindra Sangeet through his mastery over poetry.

FIG. 6. RABINDRANATH TAGORE

https://in.pinterest.com/pin/515099276128960872/

TAPPAS RECENTLY

By the 20th century, the traditional folk music of Tappa had gone through immense transformation and traveling. Recently, famous Indian music-trained Tappa singer Shashwati has collaborated with Western musicians to create a global fusion of this folk music. Most modern Tappa melodies are attributed to Shori Miyan and have been a part of the repertoire of famous ghazal singers such as the timeless Jagjit Singh and his wife Chitra Singh, both of whom sang in Punjabi. There is a famous concert of the two singing Punjabi Tappa where Chitra Ji quips – “Kothey te aa mahiya, milna toh mil aake nai tan khasma na kha mahiya” to which Jagjit Ji melodiously replies – “Ki laina hai mitra to, milan to aa jawan, darr lagta ai chitraan to…” This flirtatious banter between two lovers where the female is longing to meet on the rooftop, but the male is afraid to get caught and beaten up is a classic Tappa of Punjab which has been adapted into several modern melodies. The songs of the duo Hari and Sukhmani also have Tappa elements combined with modern music and sensibilities, such as ‘Baagay’ and ‘Latthey di Chaadar’ which are based on the above-mentioned lyrics. Although the traditional Tappa is getting diluted perhaps with contemporary ideas and musicality, and modified even for mass consumption, the touch of the Punjabi language and its roots remain timeless as the music holds up in the younger generation of today as well.

Thus, from the camel riders of Punjab to the court of Lucknow, and then the elites of Bengal, Tappa gained popularity as a pan-Indian music style under the Hindustani genre. The coarseness that inspired Shori Miyan when polished was accepted by the masses and then found its place in several gharanas of north India. However, the most unique adoption and transformation was the Toppa in Bengal wherein it was scandalous at first but then refined to the taste of the elites.

FIG. 7 An image captured at a Concert of Jagjit Singh and Chitra Singh singing Punjabi Tappa

https://www.indiatimes.com/entertainment/celebs/this-retro-video-of-jagjit-singh-and-his-wife-chitra-singing-punjabi-tappe-is-pure-gold-271106.html

REFERENCES:

- Narula, S. C. “Folk Songs of Punjab.” Indian Literature, vol. 45, no. 3 (203), 2001, pp. 182–92. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23344116.

- Francis, Z.P. “Punjabi Tappa on its Camel Journey.” (2021). https://www.academia.edu/44888636/PUNJABI_TAPPA_ON_ITS_CAMEL_JOURNEY

- Singh, N. and R.S. Gill. “Folk Songs of Punjab.” Journal of Punjab Studies, vol. 11, no. 2, 2004, pp 171-196. UC Santa Barbara. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://punjab.global.ucsb.edu/sites/default/files/sitefiles/journals/volume11/no2/6_singh_gill.pdf

- Saxena, R. “Tappa: Its Origin and Development. An analytical Study” International Journal of Creative Research Thoughts. Vol. 10, no. 5, May 2022, pp f605-f616. http://www.ijcrt.org/papers/IJCRT2205656.pdf

- https://thepaperclip.in/a-musical-journey-from-camel-drivers-to-the-bengali-household/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=a-musical-journey-from-camel-drivers-to-the-bengali-household

- https://en.rattibha.com/thread/1573529609601134592

- https://medium.com/@inz_30074/tappa-music-4c90972e9f93

- https://highonscore.com/the-art-of-tappa-singing-score-short-reads/

- https://ragatip.com/tappa-music-romantic-outbursts-of-the-punjabi-camel-riders/

- https://scroll.in/magazine/1014226/how-a-music-form-inspired-by-the-songs-of-camel-drivers-of-punjab-sindh-became-popular-in-bengal

- https://www.getbengal.com/details/bangla-tappa-born-from-banjara-music-popularized-by-nidhu-bab