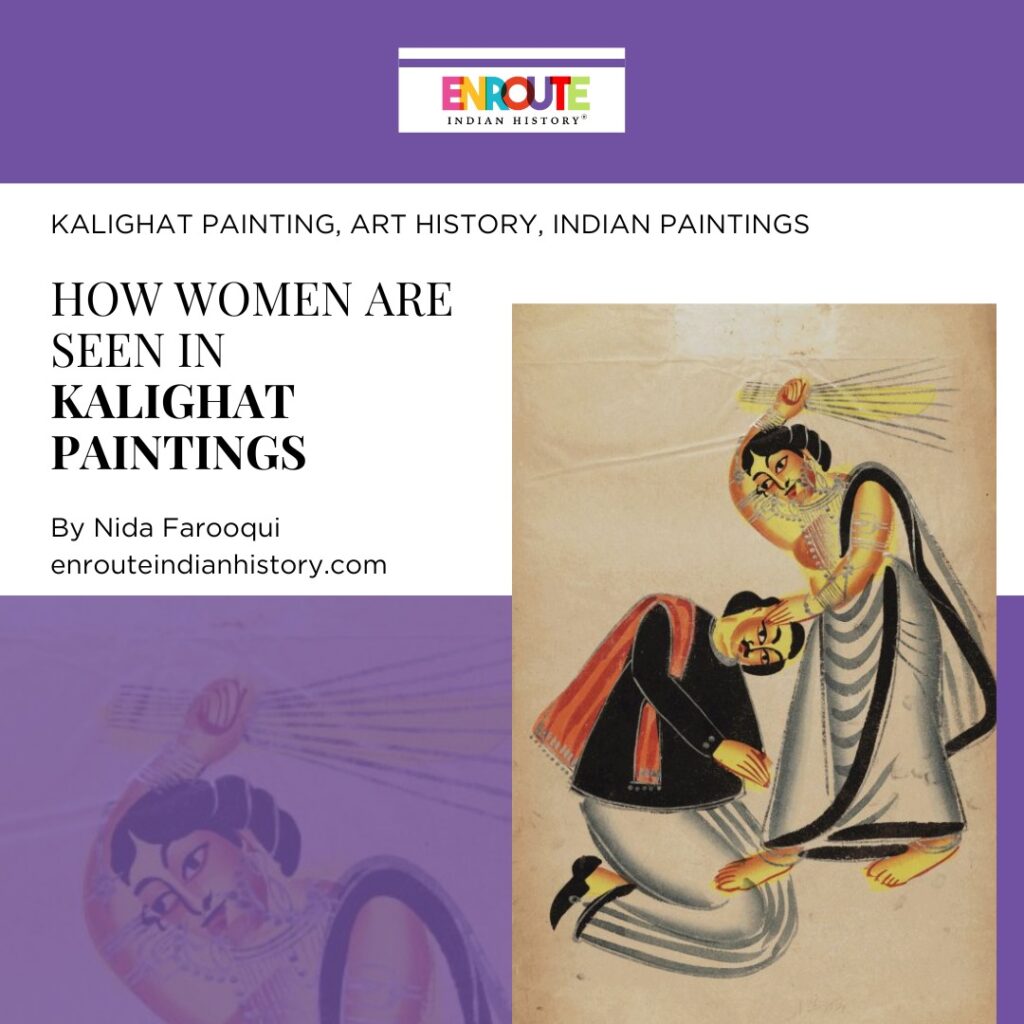

In the enchanting realm of West Bengal’s artistic legacy, the Kalighat paintings emerge as an exquisite testament to the rich tapestry of culture and societal intricacies. These vibrant canvases, originating from the vicinity of the renowned Kali Temple in Kolkata, breathe life into the tales of a bygone era. As the brushstrokes dance across the canvas, one theme that beckons our attention is the nuanced representation of women, akin to poetic verses etched in colour.

The women in Kalighat paintings stand as more than just visual elements; they embody the essence of resilience, grace, and the multifaceted roles within a society undergoing transition. Each stroke skillfully captures the complexity of their lives, presenting a compelling narrative that transcends mere artistry. These women are not passive subjects; rather, they become conduits through which the artists articulate the societal shifts and evolving gender dynamics of their time.

Amidst the vivid depictions, the canvas also unravels the subtle threads of the “Babu Culture” prevalent during that epoch. The Babus, or the Bengali gentry, are woven seamlessly into the artistic narrative, creating a backdrop that mirrors the societal norms and aspirations of the era. Through the lens of Kalighat paintings, one can discern the fusion of tradition and modernity, where the women portrayed navigate the delicate balance between tradition and the winds of change.

Step into the kaleidoscopic world of Kalighat artistry, where each stroke tells a story, and each woman on the canvas becomes a living embodiment of the societal tableau. It is a journey that transcends time, beckoning the observer to not only witness but also to feel the pulse of an era where tradition meets transformation, and women emerge as resilient protagonists in the captivating drama of life.

(Barber Cleaning a Woman’s Ear, c. 1890 ; Source – Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio, US)

In this artistic commentary, the focus often turned to the aspirations of the newly affluent Bengali native Indian clerks, commonly referred to as “babus,” who sought to emulate the dress and demeanour of their British counterparts. Kalighat painters seized upon this cultural phenomenon, employing satire to mock and ridicule the babus for their mimicry. An illustrative example features a chinless barber adorned with cleaning pins in his turban attentively cleaning the ears of a lady customer. The scene unfolds with a fashionable woman, indulging in a hookah while provocatively exposing one breast to her flirtatious barber.

The paintings further delve into the complexities of Bengali babus’ social lives, portraying neglected wives and concubines seeking companionship in the company of their servants as their husbands immersed themselves in affairs with mistresses and courtesans. Through these vivid depictions, Kalighat paintings become not just artistic expressions but critical mirrors reflecting the societal dynamics, cultural shifts, and the humorous nuances of their time.

Origins Unveiled: The Birth of Kalighat Painting Tradition

Named after the Kali Temple and situated along the banks of the Burin Ganga in south Calcutta, Kalighat paintings emerged as a distinctive art form. From the 1830s to the 1930s, these images were crafted and sold primarily as mementos for pilgrims and tourists. Beyond the alleys of the Kalighat area, these affordable artworks found their way into the market, gracing not only the shops in the vicinity but also other temples across the city. Executed with swift brush strokes on inexpensive paper, these pictures served as cherished keepsakes from journeys, adorning homes, and often finding a place of reverence on household altars dedicated to the depicted deities.

Despite its association with the renowned Hindu temple, the Kalighat painting tradition showcased a remarkable diversity in its subject matter, extending beyond Hindu themes to encompass other religious traditions and non-religious topics. Islamic representations found a place in this artistic repertoire, featuring prophets, angels, and taziyas (tomb models). The artists skillfully portrayed contemporary events, literary scenes from novels, popular proverbs, and genre scenes.

The canvas of Kalighat paintings vividly unfolded scenes from life in Calcutta’s cosmopolitan hub, capturing glimpses of English rulers, the burgeoning Bengali upper and middle classes, and the supporting classes such as servants, prostitutes, and wandering mendicants. The artists, having migrated to the city from rural fairs and festivals, documented the distinctive aspects of the urban setting that left an impression on them. Notably, even traditional Hindu deities transformed the hands of Kalighat painters, reflecting the profound impact of British colonial influence. Victorian crowns adorned goddesses, veenas were replaced with violins, and the graceful poses mirrored English noblewomen, showcasing a fusion of cultural elements in these unique artistic expressions.

The Cultural Essence of Kolkata’s Babu Lifestyle in Kalighat Paintings

In the 19th century, Kolkata, then known as Calcutta, served as the flourishing capital of British India. During this period of prosperity, a distinctive social class emerged, comprising individuals referred to as the Babus and the Bibis. The Bengali Babus, well-versed in English education, embraced a Western lifestyle, actively supported arts and culture, and demonstrated a penchant for personal grooming and fashionable attire. While their personal and professional decisions may have been subject to scrutiny, these matters are distinct and warrant separate consideration.

The spouses of the Babus, commonly known as the Bibis, exhibited a notable interest in fashion, incorporating elements from French and English styles into their wardrobes. Although the Bibis did not epitomise the empowered women we envision today, they did seize opportunities to engage in education and explore the external world, thereby displaying a degree of progressiveness that set them apart from their female predecessors.

The opulent lifestyle of this emerging wealthy class captivated the creativity of folk artists, giving rise to a distinct genre of art known as the Babu and Bibi series within Kalighat painting.

(A Kalighat Portrait of Babu and Bibi embracing by Ranjit Chitrakar, 1995 – 98; Source – Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

Situated in South Kolkata, Kalighat holds significance as a revered holy site for Hindus, dedicated to Kali, the formidable manifestation of the Mother Goddess widely adored in Bengal. Over time, Kalighat evolved into a prominent pilgrimage destination, attracting migrants in search of improved opportunities. Among these migrants were Patachitra artists, traditionally known for selling religious paintings to pilgrims as souvenirs.

Patachitra, originally a form of narrative scroll painting, involves the artist unrolling the scroll while vocalising the story. However, the Kalighat style deviated by focusing on individual scenes. Initially centred on mythological characters, the artists, inherently storytellers, swiftly transitioned to portraying facets of everyday life. As the demand for paintings waned, these artists pivoted to crafting clay sculptures of religious figures, a practice that persists in the narrow lanes of Kalighat even today.

(Portrait of Babu and Bibi by Chandan Chitrakar ; Source – Aravalli)

(Portrait of Babu and Bibi by Chandan Chitrakar ; Source – Aravalli)

Kalighat paintings serve as insightful reflections of their contemporary time and societal milieu. The artists of Kalighat utilised their craft to deliver sharp and incisive critiques, particularly aimed at the influence of the British on Indian society. Through satirical depictions and caricatures, they skillfully lampooned both British-influenced Indians and the British themselves.

During the 19th century in Bengal, the societal role of women underwent scrutiny as discussions about women’s education gained prominence. Elite women, through public discourse, managed to secure access to education, resulting in a transformation of their status from “mahila” to “bhadramahila.” In response to these societal changes, the patua, through his art, highlighted the numerous contradictions within the project of elite nationalism.

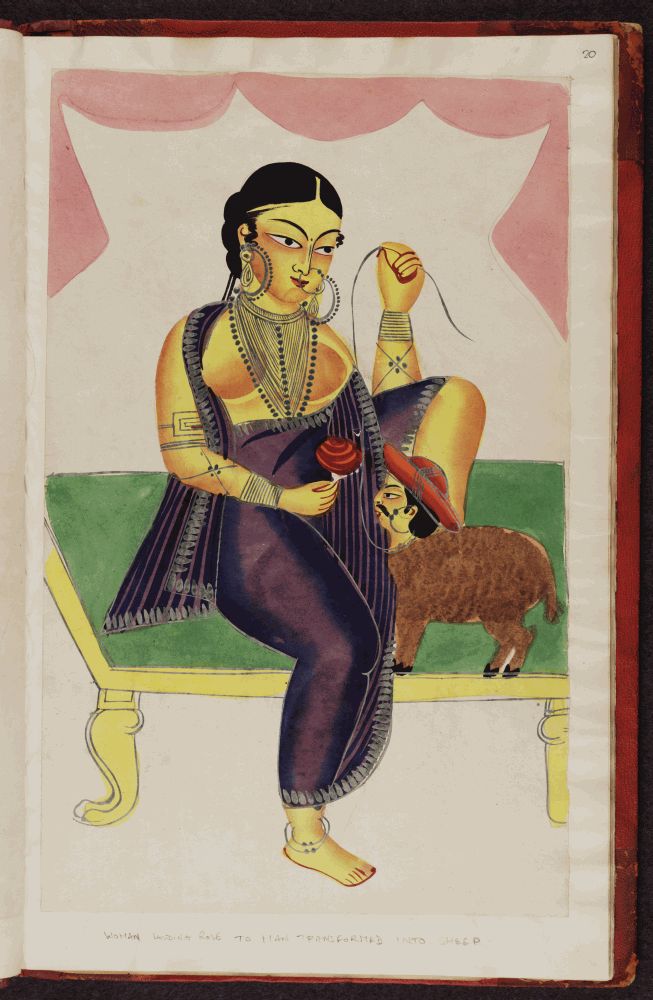

(A courtesan/actress with her sheepish admirer, Babu is portrayed as a sheep ; Source – University of Oxford)

The negative sensationalism surrounding the Kalighat school was, in part, due to the fact that the “new woman,” educated and expected to conform to social norms, did not align with the idealised image depicted in these paintings. Mukherjee elucidates how the patua deliberately created “marked differences” in their representations of prostitutes and wives. Consequently, the folk artists portrayed urban women undergoing societal changes while facing similar expectations themselves. The Babu and Bibi figures emerged as recurring themes in these paintings, serving journalistic purposes.

Anuja Mukherjee observes the subversion achieved by the patuas through the figures of the Babus and Bibis, contributing to the eventual decline of the school. She notes that when considering the extinction of an art form, it is crucial to recognize the fluidity of an entire practice, suggesting that the resonance of these paintings struck a chord that had to be silenced over time. Kalighat paintings thus became a platform through which artists expressed themselves, delving into the contradictions inherent in the self and the other, all communicated through the language of folk art embodied in the Babu-Bibi paintings.

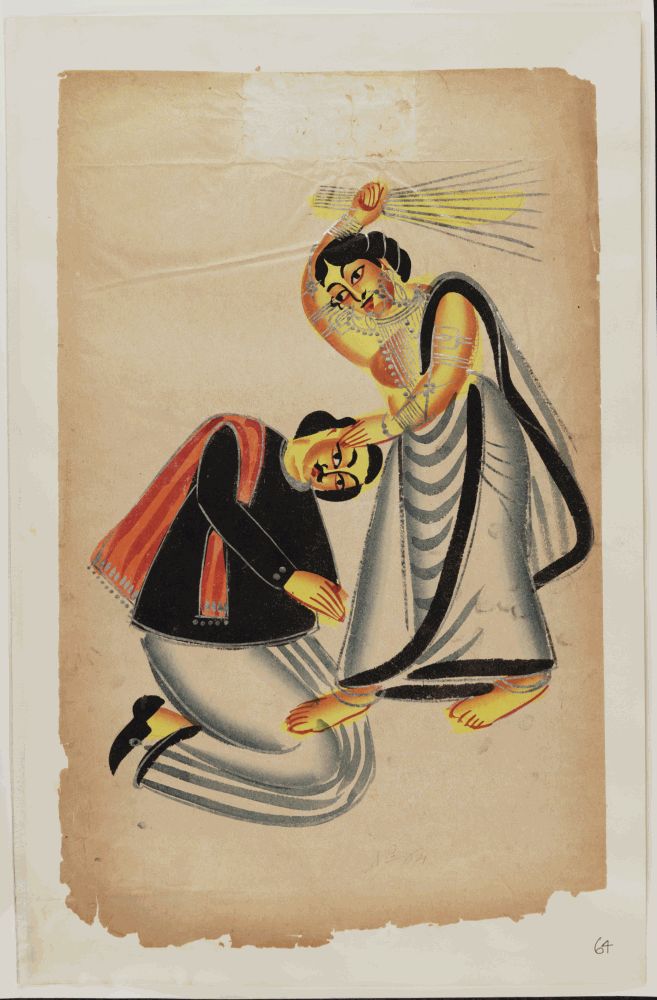

Humour has frequently served as a potent instrument for bringing attention to societal vices. The Babu culture, marked by ostentation and extravagance, was not exempt from associations with corruption and moral decay. Within the realm of Kalighat paintings, a distinct satirical undertone was unmistakable. Bibis, reflecting the satirical essence, were frequently depicted chastising Babus with broomsticks for their involvement with women of questionable reputation.

(Woman Striking Man With Broom, Calcutta, India, 1875 ; Source – University of Oxford)

The captivating journey through the realm of Kalighat paintings unveils more than just vibrant brushstrokes; it reveals a nuanced narrative of societal transformations in 19th-century Bengal. These paintings, born in the thriving capital of British India, Kolkata, eloquently capture the essence of the Babu culture and the evolving roles of women during a period marked by profound social change.

The Kalighat school, initially rooted in religious themes, evolved into a versatile canvas reflecting the pulse of society. It responded to the emergence of a nouveau-riche class, the Babus and Bibis, and offered satirical commentary on their decadent lifestyles. As the Babu culture faced societal scrutiny, Kalighat paintings emerged as a mirror reflecting the contradictions and complexities of an era transitioning between tradition and modernity.

Furthermore, these paintings became a platform for the subversion of societal expectations, with the Babu-Bibi figures serving as symbolic expressions of the changing dynamics. The satirical elements, humor, and keen observations embedded in the artworks highlighted not only the grandeur of the Babu culture but also its shadows of corruption and debauchery.

As the art form faced its eventual decline, it left behind a legacy that extends beyond its chronological lifespan. Kalighat paintings remain a testament to the power of artistic expression in critiquing and portraying the intricacies of society. Through the lens of these paintings, we glimpse the multifaceted nature of 19th-century Bengal, where tradition collided with modernity, and societal norms underwent a transformative dance. The Kalighat school, with its brushstrokes of satire and social commentary, continues to resonate, inviting us to contemplate the echoes of the past that linger in the present.

References

- Ghosh, Pika. “Kalighat Paintings from Nineteenth Century Calcutta in Maxwell Sommerville’s ‘Ethnological East Indian Collection’.” Expedition Magazine 42, no. 3 (November, 2000): -. Accessed February 04, 2024. https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/kalighat-paintings-from-nineteenth-century-calcutta-in-maxwell-sommervilles-ethnological-east-indian-collection/

- “Kalighat Paintings: A National Artefact, the Folk and Counter Representation in the Making of Modern Art in Bengal.” The Chitrolekha Journal on Art and Design, https://chitrolekha.com/v4n104/. Accessed 4 February 2024.

- Dasmahapatra, Pritha. “Kalighat Painting- from the banks of the Hooghly.” Babu & Bibi, 5 February 2021, https://babubibi.com/from-the-banks-of-the-hooghly/Kalighat Painting- from the banks of the Hooghly – Babu & Bibi. Accessed 4 February 2024.

- Archer, W.G. 1962. Kalighat Drawings. Bombay: Marg Publications.Clifford, James 1988. The Predicament of Culture. Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- May 8, 2024

- 8 Min Read