Shahjahanabad, founded by Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan in the 17th century, was a cultural, religious, and architectural hotspot. Jainism thrived in this bustling metropolis, leaving a legacy of ornate temples that served not only as places of worship but also as architectural marvels reflecting the socio-cultural fabric of the time. The intricate carvings and vibrant paintings found in these Jain temples are a testament to the artistic prowess of the craftsmen during that era. Visitors can still marvel at these historical structures today, gaining insight into the rich history and heritage of Shahjahanabad.

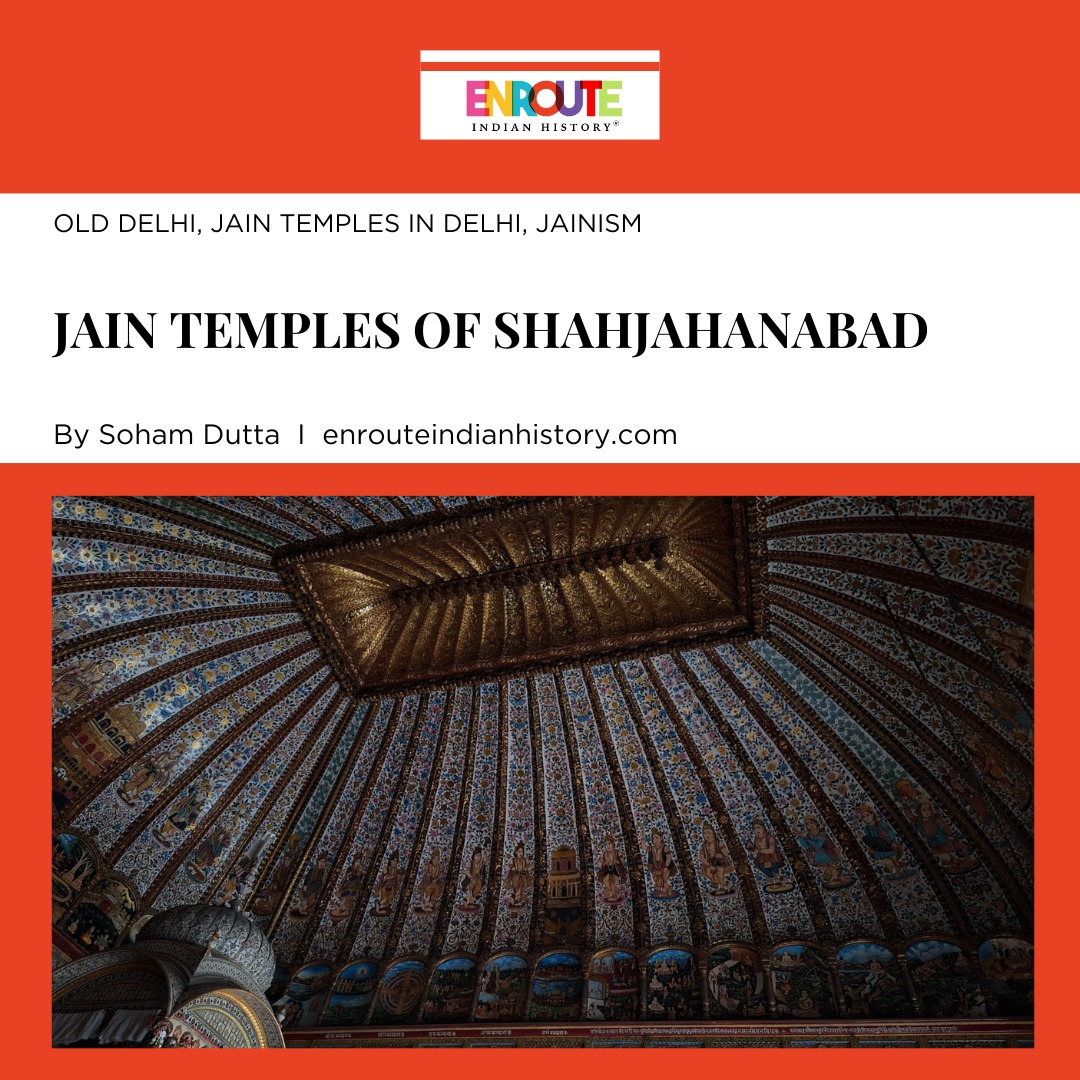

(Interiors of Central Chamber, Naya Jain Mandir, by Soham Dutta, November 2023)

17th Century Beginnings

As Shahjahanabad was established, numerous neighborhoods, known as mohallas, gradually developed within the city. These mohallas were not imposed by the imperial decree but rather formed organically to cater to the specific needs of the residents, organized according to their occupational structure. Nevertheless, an intriguing exception emerged in the neighborhood of Daiba, as its establishment and composition

(View of Digambar Jain Lal Mandir from Street of Chandni Chowk, by Soham Dutta, October 2022)

were directly influenced by a decree from the imperial authorities. This particular area was predominantly populated by Jain merchants. This was the result of Emperor Shahjahan’s extension of an invitation to Dipchand Sah, a renowned Jain merchant from Hissar, to establish his business in Shahjahanabad. A generous allocation of land near Red Fort was granted to the merchant, who is said to have constructed havelis, or grand mansions, for each of his sixteen sons. In the vicinity of the Red Fort’s Lahore Gate, a prominent temple known as Digambar Jain Lal Mandir was constructed. (Liddle,2017).

The temple is widely recognized as the oldest and most prestigious among the Jain temples in Delhi. According to ancient lore, an idol from the year 1491 CE holds great significance for the Jain soldiers, who held it in high reverence. The idol resided in a humble tent, and owing to its position within the army camp, it came to be known as Urdu Mandir (as the area was referred to as Urdu Bazar camp market) and also Lashkari Mandir, or Army Temple. After around seventy years, the Agrawal Jain community acquired ownership of the three exquisite marble idols. They proceeded to erect a magnificent temple with help of Dipchand Sah precisely on the spot where the tent had once stood, approximately in the year 1656 CE. The antechambers surrounding the main shrine to Parshvanath, the Twenty-Third Tirthankara, are adorned with intricate carvings and ornate paintwork.

The Delhi Renaissance and efflorescence of temple architecture

Although Jain Merchants and Bankers have been prominent in the Mughal court since the establishment of Shahjahanabad, it was not until the early 19th century that a significant number of temples began to emerge. In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, the artistic and cultural landscape was shaped by the dominant patron-clientele relationships, with Muslim patrons playing a significant role in artistic and cultural creations. The relationships exhibited a bureaucratic nature and prioritized patrimonial interests (Blake,1991). Furthermore, the political and socio-economic circumstances during the latter part of the 18th century posed additional obstacles to the progress of artistic and cultural endeavors. In the wake of invasions, the Empire crumbled, city was plundered, and people fled, leaving behind a desolate landscape devoid of any semblance of artistic or cultural expression (Blake, 1991). After the end of persistent conflicts and the attainment of political stability in the early 19th century, a remarkable revival of cultural, artistic, and intellectual pursuits occurred during the era of colonial rule. The phenomenon known as the “Delhi Renaissance” was coined by C. F. Andrew. During this period, patronage began to extend to the emerging middle class. During this particular era, a significant shift occurred in the manner in which financial resources were allocated for the construction of religious structures. A shift occurred from the traditional patron-client relationship to a more secular and inclusive approach, encompassing a variety of new influences. The Hindu and Jain communities, having acquired power and influence, started engaging in cultural and intellectual pursuits with the same level of enthusiasm as their Muslim counterparts (Blake, 1991). The social fabric underwent a significant transformation, which was partly due to the increase in population resulting from the migration of diverse individuals. This included laborers, artisans, soldiers, as well as bankers, merchants, and brokers. In the era under consideration, Shahjahanabad experienced a significant rise in the number of Jain merchants who founded some of the most ancient Marwari businesses in the Dharampura locality. Fergusson’s analysis emphasizes the cultural importance of this shift in architectural style. During the late 18th or early 19th century in Delhi,Fergusson notes, Jain architects emerged as pioneers in proposing a method to elevate the status of stone architecture. They sought to go beyond mere aesthetics and create structures that seamlessly integrated with their surroundings.

The Dharmpura Cluster

(Wooden gateway at ground floor; carved stone porch at first floor; Naya Jain Mandir by Soham Dutta, April 2023)

(Central Sanctum of Naya Jain Mandir with Sculpture of Lord Adinath on the platform, by Soham Dutta, November 2023)

In this era of revival , one of the most remarkable structure which came into existence, was the “Naya Jain Mandir.” Credit for this accomplishment is attributed to Raja Harsukh Rai, a prominent figure who served as the imperial treasurer under Emperor Shah Alam II and Akbar II and held the prestigious title of raja. Furthermore, he was granted the privilege to construct a shikhara on the roof of the temple. In the present day, A vibrant, painted doorway grants access to the temple, leading visitors into a narrow passage. A set of stairs leads to a meticulously designed stone porch, which serves as the primary entrance to the temple. The galleries encircle the central shrine, situated atop a raised platform. The sanctum emanates a mesmerizing splendor, with its walls, arches, and ceiling adorned in exquisite detail. The tiered and raised marble platform, adorned with exquisite inlay work, stands as a true masterpiece. A majestic figure, Lord Adinatha sits gracefully beneath a regal canopy, exuding an air of tranquility and wisdom. The image is made from Makrana marble. Two halls are located on opposite sides. In the hall to the left, a pedi is displayed, showcasing a remarkable collection of 1,008 images that depict the revered Tirthankars. At the Digambar Jain Tirth of Bharat, it is noted by Balbhadra Jain that there was originally only one vedi. After the Uprising of 1857, more vedis were built to accommodate the saved images from that chaotic time.

(One of the courtyard galleries of Naya Jain Mandir, by Soham Dutta,April 2023)

Located in the vicinity of Koocha Seth are two Jain temples, namely Chota Digambar Jain Mandir and Bada Jain Digambar Mandir. The temples possess a fascinating historical background that can be traced back to the 19th Century.

In 1840 CE, the Chota Digamabar temple was constructed by Lala Ishwari Das, a treasurer in the Mughal court, in collaboration with the Jain Panchayat.Upon entering, individuals are greeted by a grand staircase that leads them into an exquisitely adorned temple. The painted ceilings in Jain temples mesmerize visitors with their intricate designs and vibrant colors, leaving them captivated by their visual splendor. The temple is embellished with twenty-four images of Tirthankaras in the sanctum, positioned behind arches crafted from buff-colored sandstone. The atmosphere is filled with an undeniable aura of elegance and serenity. The structure boasts a grandiose domed roof adorned with elaborate paintings, accompanied by two exquisitely decorated side rooms. The temple is notable for its distinctive characteristic of having shrines located on the ground floor. In most cases, the shrines within other temples are found on an upper level, while the administrative offices are positioned on the ground floor.

The Bada Digambar Jain temple was constructed between 1828 CE and 1834 CE, with Inder Raj ji, a resident of Koocha Seth, overseeing the project. Iis notable for Tirthankar Adinathji, intricately sculpted from black marble, exudes peace atop a majestic tiered pedestal, enveloping visitors in a serene and reverent atmosphere. The platform is adorned with intricate marble screens and embellished with delicate gold-painted accents on its base.The shrine is situated on the first floor, and it can be reached by entering through a marble door that was gracefully positioned within a porch adorned with a stunning torana. The ceilings are embellished with magnificent paintings. The temple is adorned with a prominent hue of gold, which gives it a resplendent radiance.

(Gateway of Bada Digambar Jain Mandir, by Soham Dutta, September 2022)

In Muhalla Khajoor ki Masjid, there lies a Jain temple that has been eloquently described by Maulvi Zafar Hasan. This temple is none other than the Panchayati Jain Mandir. It is said that Ayamal, an officer in the commissariat department of Muhammad Shah, found himself in a precarious situation. Having fallen out of favor with his master, he lived in constant fear that his house would be seized. He devoted his property to a statue of the Tirthankar that he possessed. The shrines are once again situated on the ground floor, but this time they are elevated on a raised plinth.

One of the remarkable temples in the vicinity is the Shri Digambar Jain Meru Mandir. This architectural marvel, constructed by Lala Meher Chand in 1845 CE, stands tall with its two stories. The temple contains a visual representation of Nandishvara Dwip, which is considered the eighth island in Jain cosmology. The entrance to the temple is through a meticulously crafted sandstone doorway adorned with intricately painted wooden doors. The primary shrine is located on the first floor and is adorned with intricate paintings on both the walls and ceilings.

Located at the end of a cul-de-sac in Naughara, the Shwetambar Jain Mandir, also known as Jauhri Mandir, stands in a nearby neighborhood. According to Bashiruddin Ahmad Dehlvi and Maulvi Zafar Hasan, esteemed authors of the early twentieth century, the age of this particular subject can be traced back 200 years. According to Dehlvi, the temple is believed to have been established by the Jain community during the reign of Emperor Shah Jahan. The temple is adorned with exquisite paintings and decorations, just like other Jain temples. The shrine is located on the upper floor, a deliberate choice made to maintain the sacredness of the images. The focal point of the sanctum houses the image of Sambhava, the revered third Tirthankara. Other Tirthankaras are also depicted in the images, including Neminath, the 22nd Tirthankara, Vimalnath, the 13th, and Parshvnath, the 23rd.

The Jain heritage of Shahjahanabad is a living testimony to the city’s illustrious history, interwoven with the city’s many cultural, religious, and architectural wonders. The historic metropolis of Delhi bears witness to the enduring legacy of Jain merchants, craftsmen, and devotees. Whether it is the Mahaveer Bhavan in Chandni Chowk, which had a crucial impact on the Freedom movement, or the bird hospital that still offers medical attention to birds, the city is a vibrant combination of busy streets and peaceful temples. The Jain community in Shahjahanabad has made a lasting impact on the city’s landscape, with their contributions spanning centuries and enriching the cultural fabric of Delhi.

References

- Blake, Stephen P. Shahjahanabad. Cambridge UP, 1991, books.google.ie/books?id=vJ0e0kfgttUC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Sthephan+blake+shahjahanabad&hl=&cd=1&source=gbs_api.

- Safvi, Rana. Shahjahanabad. Harper Collins, 2019, books.google.ie/books?id=91mwDwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=Rana+Safvi+shahjahanabad&hl=&cd=1&source=gbs_api.

- Dayal, Maheshwar. Rediscovering Delhi. New Delhi : S. Chand, 1975, books.google.ie/books?id=y7YBAAAAMAAJ&q=shahjahanabad&dq=shahjahanabad&hl=&cd=3&source=gbs_api

- Liddle, Swapna. Chandni Chowk. 2017, books.google.ie/books?id=VXeinQAACAAJ&dq=chandni+chowk+swapna+liddle&hl=&cd=1&source=gbs_api.

- Goel, Vijay. Delhi, the Emperor’s City. 2003, books.google.ie/books?id=GFVuAAAAMAAJ&q=chandni+chowk&dq=chandni+chowk&hl=&cd=2&source=gbs_api