“Jal” in Kangra Paintings: The Sacred Flow of Love and Nature

- EIH User

- August 21, 2024

Since ancient times, Indian culture has held water in veneration since it is essential to daily life, mythology, and rituals. This holy component has long been present in the nation’s artistic and spiritual traditions, appearing in a variety of historical art forms. Water is also celebrated in a number of ways, from elaborate temple carvings to traditional dance performances. In particular, water has long been shown in paintings as a representation of holiness, vitality, and heavenly energy. Within this is the Kangra school of painting, which is renowned for its vivid colors and delicate brushstrokes. It also depicts water in a unique way, frequently using tranquil lakes and ponds, tumbling waterfalls, flowing rivers, and pouring rain as essential components of its compositions.

The origin of this Pahari painting was an exceptional event that took place in the hills of Punjab in the middle of the eighteenth century A.D. The plains of northern India were shaken by the invasions of Ahmad Shah Abdali (1739) and Nadir Shah (1739). Raja Govardhan Chand (1744–1773), a prince with sophisticated taste and a passion for paintings, was the patron of the Kangra School of Painting at Haripur–Guler. He granted asylum to artists who were refugees and had studied under the Mughal painters. The Mughal style, with its delicate naturalism, flowered into the Kangra style in the inspiring surroundings of the Punjab Himalayas, with its stunning green hills, wave-like terraced rice fields, and rivulets supplied by the glacial waters of the snow-covered Dhauladhar.

With origins in the Lower Himalayan Guler Paintings and the Basohli Paintings of Jammu, Kangra Painting depicts the region’s topography, and the long-standing relationship between nature and the sacred in Indian philosophy and aesthetics is reflected in the emphasis on water. Water is portrayed in stories as a means of conveying atmosphere, emotion, and the passage of time, as well as serving as a cultural and mythical anchor.

Historical Context: Nature and Myth in Kangra Art

The Pahari school of painting, which emerged from the previous Rajput style but was characterized by its fine details and attention to nature, included the Kangra School. The painters were naturally inspired by the lush, harmonic compositions they created, drawing from the surroundings of the Kangra Valley. The representation of divine love, which is the main focus of this school of art and is mostly based around themes of Krishna, Radha, and the Bhagavad Purana, is combined with pieces that are influenced by Sanskrit writings such as the Gita Govinda.

In these tales, water is an essential component, both literally and metaphorically. Rivers and lakes serve as the setting for stories of divine love in mythological artwork. One such story is the Rasa Lila, in which Krishna dances with the gopis along the Yamuna river. Moreover, rivers represent life, cleanliness, and rebirth in Indian philosophy, where they are revered. The Kangra School’s depictions of water uphold the aesthetic standards of grace and elegance while simultaneously reflecting this spiritual significance.

(Radha-Krishna enjoying the scenic rain, Kangra illustration)

(The Joys of Rain, Kangra Painting)

The Yamuna River: A Spiritual and Aesthetic Force

One of the main water themes in Kangra paintings is the Yamuna River, which is revered and frequently connected to the goddess Yamuna. According to the Kangra School, the river is a living being, a place where the divine manifests itself rather than just a physical characteristic. Krishna is often shown with his loving gopis, either bathing in the Yamuna or standing beside it in the Rasa Lila episodes. Here, water becomes a catalyst for divine playfulness, creating an area where the realms of heaven and earth collide.

(Radha’s tryst with Krishna at the banks of the river Yamuna, Godhuli: The Hour of Cowdust, Illustration to a verse of Kashiram, Guler)

Some Kangra paintings depict the Yamuna with subtle curves and glistening blue colors that resemble the movement of water, with lush foliage adorning the banks. The river’s reflective surface is frequently employed to intensify the heavenly or romantic ambiance. For instance, the calm and affection that permeate paintings depicting Radha and Krishna meeting by a river are created by the delicate reflections and ripples. The heavenly love between Radha and Krishna seems to be eternal and virtually suspended in time because of the ethereal atmosphere these representations produce.

Radha, together with her companions, reaches the bank of the river to fetch water. (Both Radha and Krishna are love-struck and gaze intently at each other.)

Krishna dances on the multi-headed hood of the serpent Kaliya.

(in the river Yamuna)

(The Gita-Govinda series, depicting the meeting places of Krishna and Radha on the banks of the river Yamuna in the plains, customarily features thick clusters of trees.)

In one such well-known Rasa Lila artwork, Krishna and the gopis are depicted dancing joyfully on the banks of the river in a semi-abstract manner. The joyful rhythm of the landscape is reflected in the flowing water, which represents both cosmic harmony and emotional mobility. The Yamuna is frequently associated with a profound spirituality that emphasizes grace from above and purity.

(Krishna with his Gopis at the river Yamuna, a folio from the Lambagraon Gita Govinda series, school of Purkhu, Kangra)

Monsoon and Rain: Evoking Mood and Emotion

One further recurrent theme in Kangra paintings is water, which is shown as rain or the monsoon season. This motif is frequently used to suggest mood, emotion, and time passing. Within the realm of Indian classical poetry, the monsoon season is frequently linked to yearning and separation, especially in the Baramasa (a genre that illustrates a year’s worth of events) and Nayaka-Nayika Bheda (a tale of a hero and heroine’s love and separation).

Dark clouds and the image of gathering clouds speckled with rain and lightning manifest the language of symbols, rendered in visual form through seemingly decorative details.

Two royal ladies strolling in a hilly landscape

(Guler, 1600, Jagdish and Kamla Mittal Museum of Indian Art, Hyderabad)

As Nayika hurried to meet her beloved, snakes got entangled around her legs, and more were trampled under her feet. Goblins stared at her from all sides, and there was heavy rain. But she paid no heed to any of these, neither to the sound of the crickets nor to the thunderous clouds.

(Abhisarika nayika, Guler, ca. 1800, Sri Pratap Singh Museum, Srinagar)

(In depictions of this episode, the Rain God Indra is usually shown astride the elephant Airavata amidst dark clouds, threatening torrential rains.)

Kangra art depicting monsoon settings encapsulates the romance and drama of the season. While torrents of rain shower down, swirling clouds darken the sky and make a striking contrast with the verdant surroundings. In these paintings, the water is portrayed metaphorically, frequently signifying the lover’s tears or the overflowing feelings of need and passion. A famous illustration of this is a painting of Radha and Krishna in the monsoon, with rain gently falling around them and thundering clouds amassing overhead. Here, water takes on the role of an extension of their feelings, intensifying their unity and love.

(Lord Krishna and Radha are standing under a tree with a rug over their heads to be safe from rain.)

(Krishna is portrayed as Nayak and sad Nayika, requesting him not to go away during the monsoon season.)

The clouds covered in rain and the ensuing downpours are frequently painted with careful consideration, capturing the mood of the season with delicate brushstrokes. These paintings depict a sensual encounter with nature, where water takes on dual roles as a calming and potent force that may alter both the surrounding scenery and the feelings of the people who inhabit it. The monsoon is portrayed in some as a source of relief for arid regions, signifying fertility and rejuvenation, and in others as a setting for romantic moments spent alone or reunited.

In addition to rivers and rainfall, ponds—which are frequently found inside elaborate gardens—also represent water. Often, these landscapes feature heroines or courtesans relaxing by the water’s side, with lotus flowers and vegetation framing their reflections as they shimmer in the quiet water. The characters’ reflective demeanor is reflected in the tranquility of the water, which creates a pensive, even dreamlike ambiance.

Particularly, ponds have a special position in the Kangra School’s aesthetic lexicon. They are associated with the Indian artistic tradition that sees water bodies as nurturing areas, and they frequently represent femininity and fertility. Some paintings feature a heroine sitting next to a pond full of lotuses, either staring at her reflection or waiting for her love to arrive. Smooth as glass, the water reflects not only the heroine’s beauty but also her innermost feelings, whether they be contentment, longing, or anticipation.

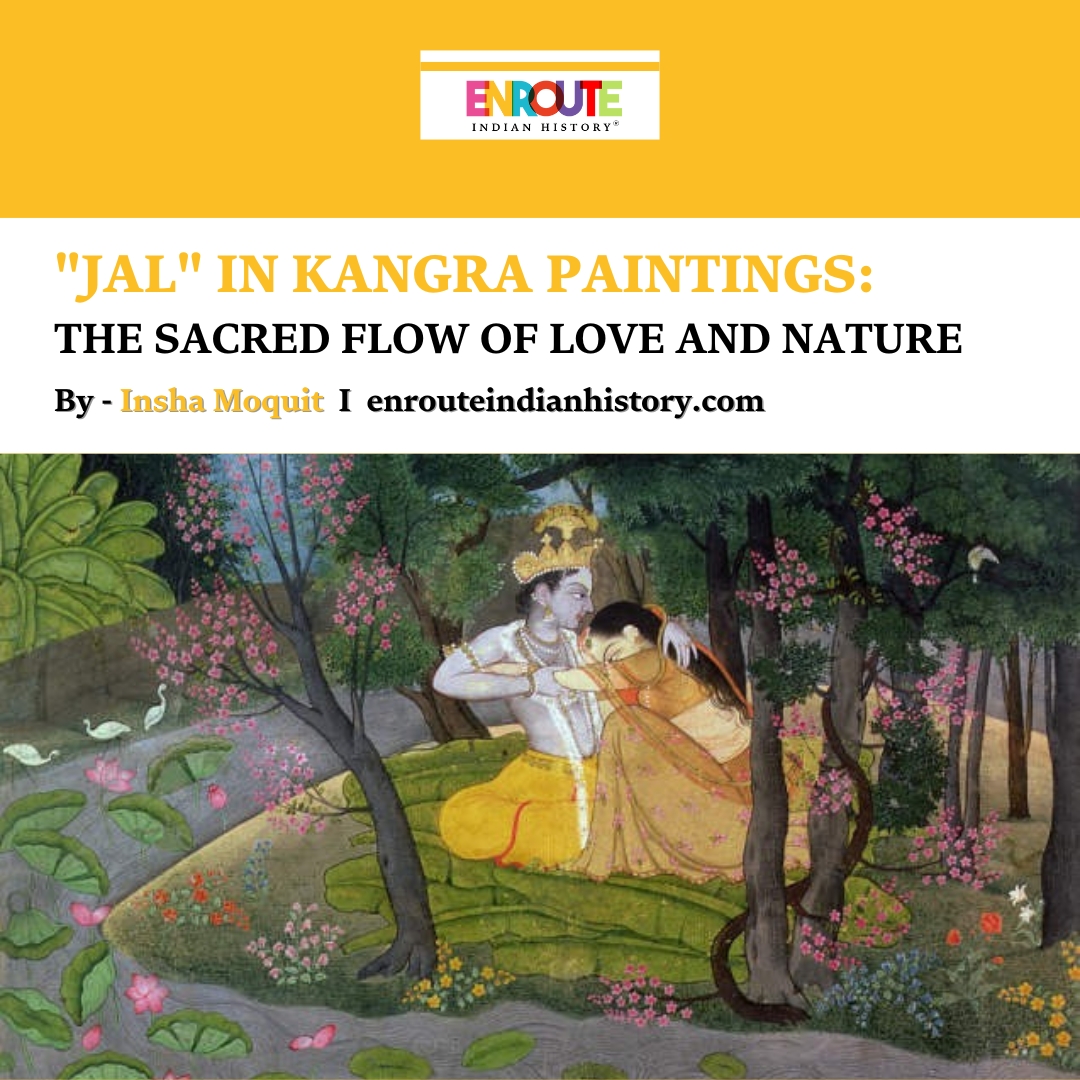

Ponds are also frequently shown in Kangra paintings as serene locations where Radha and Krishna meet, reflecting the rich terrain of the area. These artists illustrate tranquil water bodies surrounded by lush foliage with skill, using vivid colors and subtle brushstrokes. Lotus flowers are commonly displayed in the ponds, signifying divine love. Depth and mood are added by the water’s reflections. The picturesque view is enhanced by the painters’ use of minute details in the surrounding flora and fauna.

(Krishna and Radha embracing in a grove, Kangra, Himachal Pradesh, c.1785)

Conclusion: Water as an Element of Beauty, Emotion, and Divinity

In Kangra paintings, water in all its manifestations is a recurrent and fundamental element that represents emotional states, the surrounding natural environment, and heavenly love against a background. Water has a symbolic meaning. It symbolizes life, love, longing, and spiritual purity. The Kangra School crafts a universe in which water is not just a physical presence but also an essential component of the emotional and spiritual landscape through its subtle yet evocative portrayals.

Water not only runs through the Kangra valleys but also through the thoughts and hearts of the people shown in these miniature works of art, sculpting their tales and feelings in the same way that it does the surrounding terrain. Water paintings from the Kangra School thus become a poetic representation of the interplay among nature, the divine, and human experience, all of which come together to form a lovely, harmonious whole.

REFERENCES

Dehejia, Harsha V., et al. Painted Words: Kangra Paintings of Matiram’s Rasraj. 2012, ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BB09916282.

Dallapiccola, Anna L., and M. S. Randhawa. “Kangra Paintings of the Bihari Sat Sai.” Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 90, no. 4, Oct. 1970, p. 591, doi:10.2307/598856.

Goswamy, B. N. “The social background of Kangra valley painting.” Shodhganga, Jan. 1961, shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/handle/10603/106907.

Khandalavala, Karl. Pahari Miniature Painting. Bombay: New Book Company, 1958.

Randhawa, Mohindar Singh. “Kangra Painting on Love.” National Museum eBooks, 1961, ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA46595817.

— “Kangra Valley Painting.” Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Govt. of India eBooks, 1972, ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA52030835.

Randhawa, Mohindar Singh, and W. G. Archer. Kangra Paintings of the Gīta Govinda. National Museum eBooks, 1963, ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA23727861.

Rao, Bhaskar D. Pahari Miniatures in the Salar Jung Museum, Hyderabad. Hyderabad: Salar Jung Museum, 1996.

“Kangra painting – Google Arts and Culture.” Google Arts & Culture,

https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/kangra-painting/eQGunyaThJNufA