Leh Palace: Epitome of Royal Heritage & Traditional Tibeto-Himalayan Architecture

- EIH User

- April 18, 2024

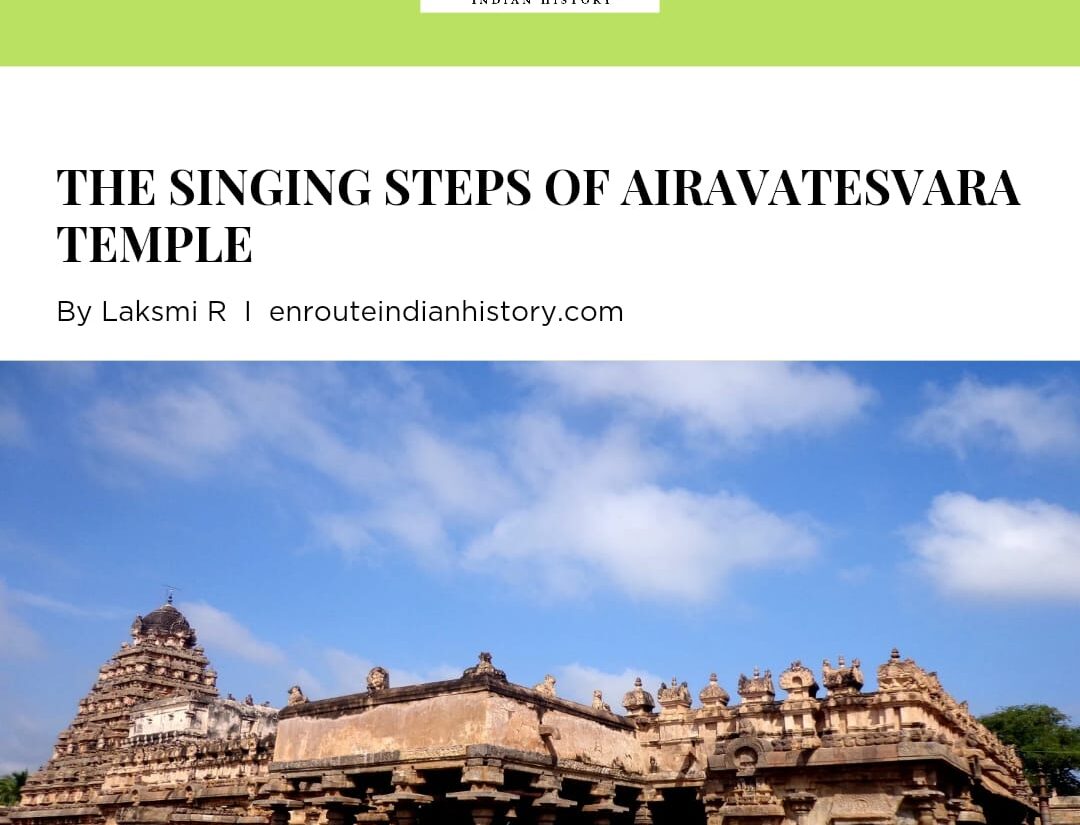

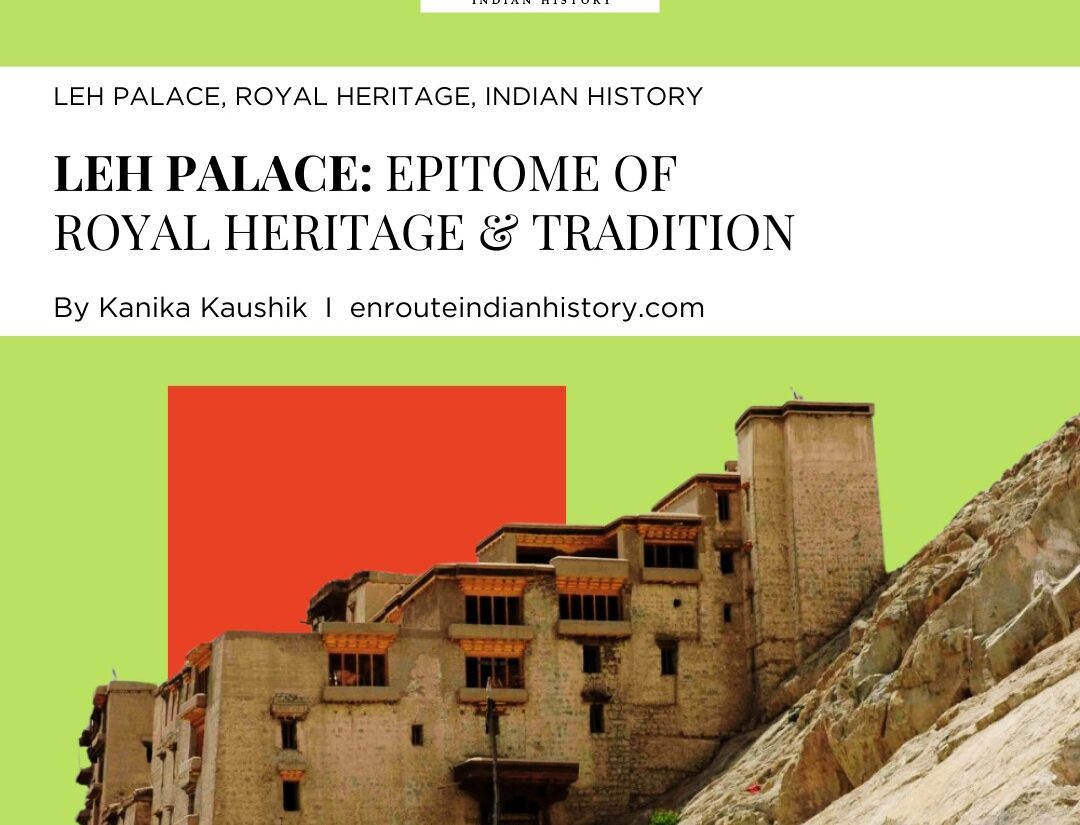

As you approach Leh, the capital of Ladakh, you can’t miss the grand Leh Palace atop Tsemo Hill. Built in 1553 by King Senge Namgyal, it’s a nine-story marvel known locally as Lhachen Palkhar. Legend says the king chose this spot because it resembled an elephant’s head. Skilled craftsman Chandan Ali Singge completed the Leh palace in just three years, showcasing exceptional skill. Its beauty was so admired that the king ordered the chief mason’s hand severed to prevent replication. At its construction, Leh Palace was the highest building in the Himalayas; its fame transcended the boundaries and continued to draw scholars, tourists, and military men. William Moorcroft was the first Westerner to document Leh and its palace, who lived in Ladakh from 1820 to 1822. However, Alexander Cunningham provided the first brief description of the palace when he first saw Leh in 1854.

The Leh palace is a prime example of Traditional Tibeto-Himalayan Architecture, showing the finest craftsmanship of Ladakh. Its design, materials, and decorations all reflect traditional Tibetan building techniques. One striking feature is its battered wall construction. Following Tibeto-Himalayan tradition, the palace comprises nine levels, with two sublevels added to accommodate site conditions. It reaches a towering height of nearly 60 meters, from the base of its southern walls to the summit of the ninth level. The upper levels hosted noble functions like royal apartments, staterooms, temples, and ceremonial halls. In contrast, the lower levels served practical purposes such as storage and stables.

The heart of the Leh palace lies in its central courtyard, located on the fourth level and about 40 meters above ground. This courtyard was the hub of social and cultural activities for the royal family and the government. Built on a granite saddle, the palace follows traditional methods of massive masonry construction. Its foundations and cross walls support the external and internal walls. The heavily battered walls start at a thickness of 1.75 meters at the base and taper down to about 0.5 meters, where the stonework transitions to sunbaked brick.

Tibeto-Himalayan Architecture

(Leh Palace : Colour by Alexander Cunningham)

The Leh palace’s foundations are firmly set on the rock, following the natural shape of the granite saddle. The upper parts of the construction, where the weight is lighter, are made of sun-baked brick, a common material in local homes. Floors are made of rough timber, spanning either the walls or, in larger rooms, the beams and pillars. A layer of twigs or small pieces of wood laid over the beams supports the clay floor, which varies in thickness. The importance of a room is often shown by its size, the number of pillars, window size, and the quality of its carving and decoration. The palace showcases the best of Tibeto-Himalayan architecture, using local materials and skills to the fullest. The stonework, especially the external walls, is of exceptional quality. Each stone had to be carefully chosen and shaped to fit the curved walls precisely. Timber beams were introduced regularly to support the stonework and maintain its pattern throughout the walls.

Cross-walls made of granite, resembling a grid, rise from the depths of the building, providing crucial support to the base of the external walls. The upper walls are made of compact clay blocks mixed with random stonework, lightening the load on the walls below. The windows’ design, size, and proportions are typical of Tibeto-Himalayan architecture, adding to the Leh palace’s distinctive character. The palace’s outer south and inner spine walls receive support from sturdy cross-walls. These walls start at a thickness of at least 1.75 meters at the base and gradually decrease to about 0.5 meters, where the stonework transitions to sunbaked brick.

A grid of 16 pillars is often needed to support the structure in large rooms used for gatherings. The flat roofs, typical of this dry area, provide little protection from rain but create functional terrace spaces for various activities. Externally, the Leh palace has trellis work and simple carvings on the lintels above the windows. Internally, walls are plastered with mud mixed with barley chaff, and finer clay plaster is used in more critical rooms. Decorative elements like circular motifs on lintels and stacked twigs on parapet walls add to the aesthetic appeal.

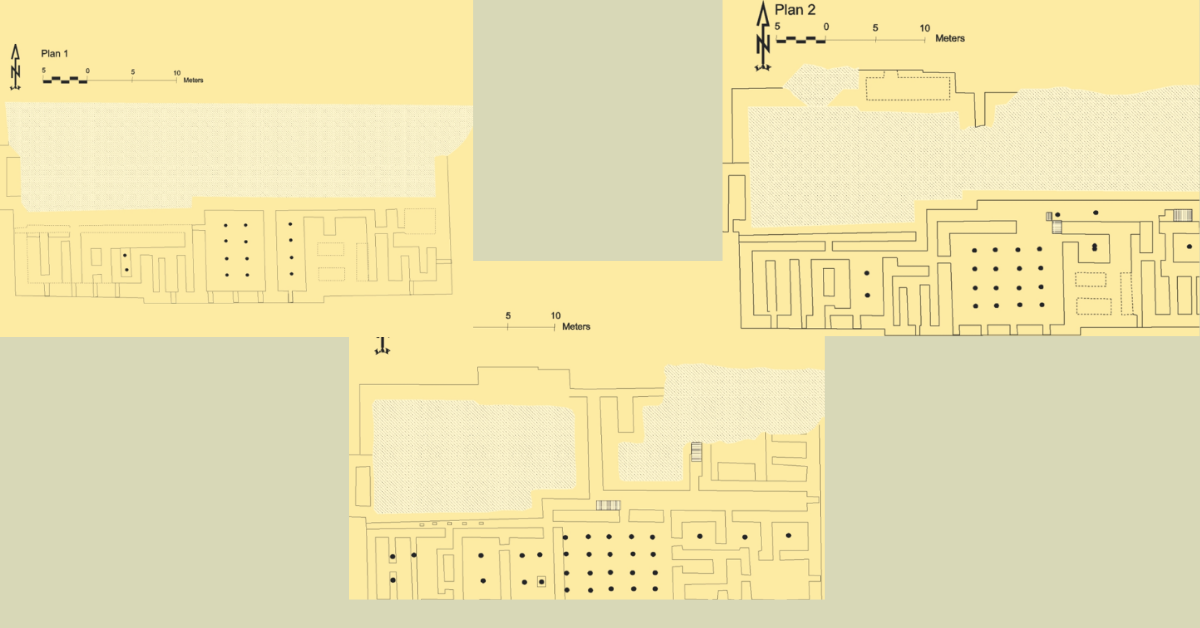

The layout of the palace

(Source: https://www.ladakh-tourism.net/blog/leh-palace/)

The nine-story building’s Himalayan architectural design indicates it had been an administrative construction rather than a warrior’s residential place. To look at levels, Starting from the first level on the south side of Leh Palace, empty spaces go down two more levels to form the foundation. These lower levels are shown externally with a few small openings that don’t necessarily match specific floor levels.

On the second level, on the east side, there’s a fancy porch that serves as the main entrance to the Leh palace. It’s made of carved timber and depicts the Snow Lion, the king’s emblem as Sengge Namgyal, popularly known as the Lion King. A lion’s head, representing the king, is placed above the door.

Dental traditions state that it opened its mouth and roared at undesirable traffic to show the king’s energy. The king would sit on a large throne on his patio with aristocrats seated lower than his to demonstrate their reverence and position. The entrance corridor, carved into the rock, bypasses this level and leads to the third level, mainly to the courtyard at the fourth level. At the third level, the foundation grid is established, with silo openings cut into the granite rock saddle, about 2.60 meters in size. At the fourth level of the Leh palace is the central courtyard and the temple known as Duk-Kar Lhakhang. Level five is quite significant. It houses the main assembly hall, or hall of audience, which is about 10.45 by 17.45 meters in size and situated at the southeast corner. Initially, you could access this hall directly from the central courtyard via a staircase. Moving up to level six, you start to see the overall layout of the Leh palace. This level was mainly where the royal family lived, with reception and retiring rooms primarily located in the southeastern part. The central area likely housed the kitchens and storage rooms, while additional living spaces were in the eastern section. Level seven is the official ceremonial area, with three separate sections: the throne room, the temple, and the east-facing royal chamber. The large terraces to the southeast were used as gathering spaces during official events. On level eight, only a few auxiliary rooms are in the northeastern corner. Following tradition, the summit of the Leh palace is reached at level nine. This level consists of one room where worship to the Gurlha divinity was performed.

(Leh Palace Floor Plan : Source- Ladakh Tourism)

Although there are likely over a hundred rooms in the palace, only a few can still be identified as significant. The principal rooms include the main temple, Duk-kar Lhakhang, located at level four, and the throne room, temple, and royal chamber at level seven of Leh Palace. These rooms were crucial for various functions and ceremonies within the Leh palace. The central courtyard of the building served as a gathering space for performances, including song recitals and dancing. These events were for the royal family’s entertainment and were performed by the Takshosma, who hailed from ten different households in Leh City. One such member, Padma Angmo of the Nochung family, reached 98 in 2018 and is now the sole surviving Takshosma. She recalls how the dancers, led by the Lhardak family, performed ‘Kathog Chenmo’ for the king and queen, especially during the Dosmoche and Losar celebrations. Despite the royal family no longer residing at Leh Palace, they would still attend these festivities, arriving from Stok with a large entourage.

(Contemporary Condition- Source: World Monuments Fund)

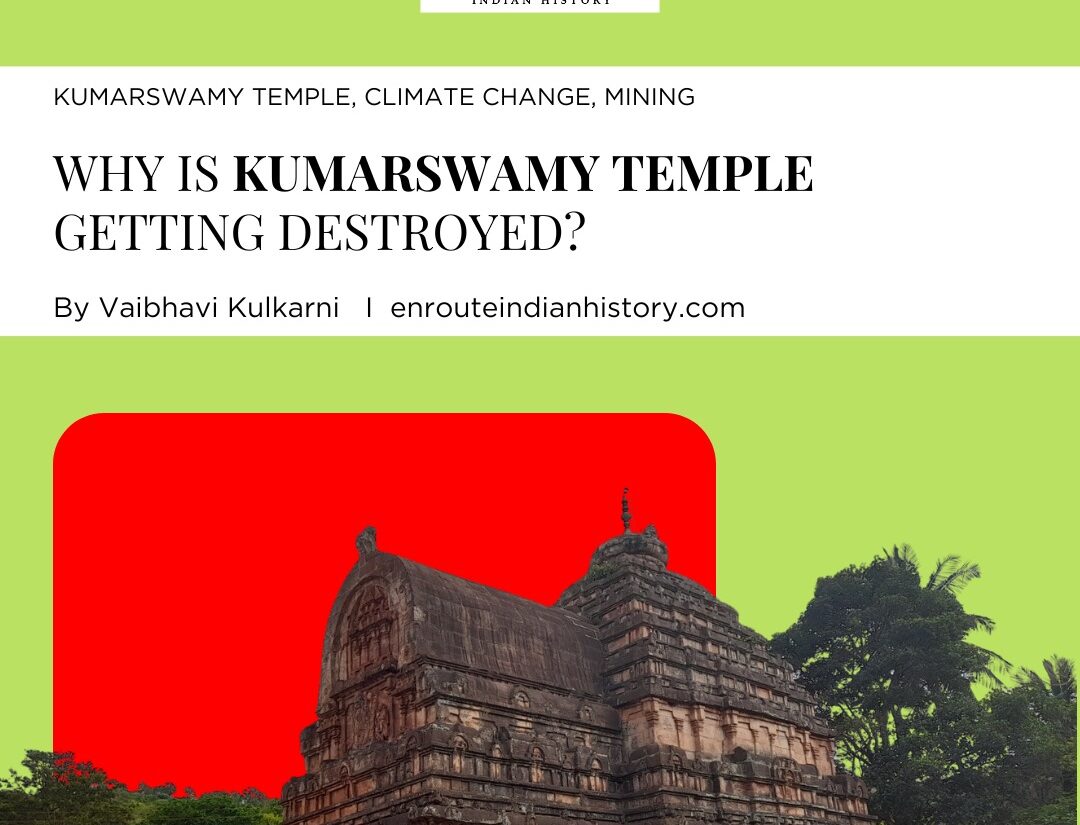

After the Dogra war, the royal family moved out of Leh Palace and stayed in Stok Palace in the mid-19th century. With the king’s departure from Leh, the areas surrounding the Leh palace lost their significance and glory. People began to follow the king and settled in areas further down from Leh Palace, which developed more rapidly than the steep slope directly below the palace. Leh Palace gradually fell into disrepair without its residents and regular maintenance.

In 1995, the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) initiated renovation plans, starting with some initial repairs. Then, in 1998, they began significant renovation and restoration work. Conservation efforts have been crucial since the nineteenth century to protect the palace. Leh Palace represents the identity of the people of Ladakh. Since 2003, the Tibet Heritage Fund has been working with the local government on a restoration plan. Finally, in 2008, Leh Old Town was added to the World Monuments Watch list.

In contemporary times, Leh Palace has become critical as Leh Old Town is a rare example of a historic Tibeto-Himalayan urban settlement. It’s unique because only a few urban centers existed in the Himalayan high plateau, and even fewer survive today.

REFERENCES

- Jest, C., & Sanday, J. (1983). The Palace of Leh in Ladakh: An Example of Himalayan Architecture in Need of Preservation. Mountain Research and Development, 3(1), 1-11. Published by: International Mountain Society

- Cunningham, A. (1854). Ladak: Physical, Statistical and Historical. London: Allen & Co.

- Cook, J., & Sakya, T. (1983). Six Families of Leh. In D. Kontowsky and R. Sander (Eds.), Recent Researches on Ladakh, Vol.1, History, Culture, Sociology and Ecology. Munich.

- Wangmo, Tenzin, and Tashi Wangyal. “Historical and Cultural Significance of Leh Palace.” 2021.

- May 15, 2024

- 6 Min Read