“Time and space are but physiological colors which the eye makes, but the soul is light”, writes Ralph Waldo Emerson in his essay “Self-Reliance” (1841). To describe the soul as light seems only symbolic, but centuries before Emerson, in ancient Indian art and culture, not only was light seen as an extension and expression of the soul, but was also depicted in material art- sculptures and paintings. Ancient Indian traditions, from the time of the Vedas, are filled with reverence for the glowing light of the Sun, which was the most visible proof of the divine and its powers. “Prakasha” and “Teja” (both Sanskrit-Hindi terms for light), were valued as the primordial source of all life and beauty, entrenching light in the psyche of Indians from early times as a symbol of all that is sacred and worthy. Over time, this reverence for light grew, making it a motif used in art to suggest the glory of the heavenly beings. Considered a predecessor of aura, halo, and aureole of European art, the circle of light in Indian art was called Prabha, Prabhavali, and Mandala, each with its meaning and symbolism, resulting in a brilliant artistic tradition of light being expressed in stone, metal and later, on paper in Indian history.

Glowing Bodies: Light as a Divine Virtue

“With his luster and steadfastness he appeared like the young sun come down to earth, and despite this his dazzling brilliance when gazed at, he held all eyes like the moon. For with the glowing radiance of his limbs he eclipsed, like the sun, the radiance of the lamps, and, beauteous with the hue of precious gold, he illuminated all the quarters of space” (Johnston 2015, 4). These poetic verses describe the birth of Siddhartha (Buddha) in the groove of Lumbini, from the Buddhacharita of Ashvaghosha, an ancient authority on the life of the Enlightened One. Emphasis is given to the luster and glow of the young Shakya prince which filled the space with the light of the Sun and Moon. This case of describing “radiance” or “aabha” as the proof of a divine being’s transcendental qualities is not an isolated one. From Hindu to Buddhist and Jain cultures, light around the figure of a god or goddess, the origin of deities from a Prakasha-Punja or ball of light, and a solar disc around their countenance is an established tradition. The Chitrasutra, a treatise on making icons and art from early Indian history, describes how halos around divine beings are to be depicted. Even in the early Vedic traditions, the birth of the Universe and its progenitors Brahma and Rudra has been connected with fire and light (Kramrisch 1988, 15).

Where Did Halo Originate?

Much like many other aspects of Indian art, the halo has been the center of a rich academic debate for decades. While some including the illustrious art historian Ananda Coomarswamy argued that the halo or aura (Prabha, prabhamandal) has Indian roots, many opined that it was derived from Iranian and Greek art, especially because of its use in Indo-Greek or Gandhara images of Buddha. Those who suggest an Indian origin for the lustrous ring of light around divine and human figures, point to the existence of reverence of light in Vedic rituals and mammoth sculptures and golden coins of the Kushana rulers, showing them surrounded by solar auras (Sudhi 1985, 255).

5th Century Buddha from Mathura (Source: Flickr, Nathan H. Hamilton)

Linguistic evidence has also been extended, reading the Italian “mandorla” to the Sanskrit term “mandala”, which describes the circle of light in philosophy and art. (Chumak 2020, 18). With a multitude of textual and material evidence using light as an expression of divinity from the earliest phases of Indian history, one can comfortably assume that the halo as Prabha, prabhamandala, and aabha originated in India and had an indigenous aesthetics in the art of the country, before interacting with the iconography of the world. Some of the finest examples of light in Indian art as halo or aura can be seen in the aureole or Prabhavali (garland of light) around the cosmic dancer, Nataraja, aura around Buddha’s statues, and Siraschakra, the circular head ornament as a stylized symbol of divine aura, used as an ornamentation in the Chola bronzes of Uma (Shiva’s consort).

Differentiating Between Prabha, Prabhavali and Siraschakra

The halo or aura finds one of its earliest delineations in the classic aesthetics of Gandhara art, where Buddha wrapped in beautiful folds of Cheevara (monk’s garments) stands tall as “the” representative of early Indian art. The stone sculpture of the standing Buddha from Gandhara (2nd century) currently residing in the National Museum Delhi, features a simple disc around Tathagata’s head, suggesting his transcendental qualities. Seated and standing Buddha sculptures from Mathura too, show him surrounded by a Prabha (aura), which grows ornate as we enter the Gupta period, with rich and stylized motifs added to the circular form.

Chola Nataraja Bronze Statue with Prabhavali (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The popularity and space (literally) of divine light and Prabha seems to grow with time in Indian art and history, as we move from the ancient to the early medieval period. Witnessing the dance of Shiva in metal, in the icon of Nataraja, one of the most popular symbols of the art of India, what probably strikes the most is the lyrically round “ring of fire” in which Shiva dances. The Prabhavali or garland of light around Nataraja symbolizes the effulgence that emits from the deity during the dance as well as the cosmic feminine principle or Prakriti, surrounded by which Shiva, the primordial male (Purusha) conducts his cosmic action. In Southern Indian texts, tiruvasi is the term used for Nataraja’s aureole, as a fiery circle that marks the glory of the Lord of Dance (Sudhi 1985, 256). As an integral part of Nataraja’s iconography, the aureole or Prabhavali or Prabhamandala (circle of light) is one of the most stunning examples of light captured in Indian art.

Chola Uma Bronze, observe the reverse of the icon for the stylized Siraschakra (Source: CA and A Exhibition)

The experiments of early Indian artists with Prabha or aura can also be seen in the case of Siraschakra (the circle or chakra around the head or sirsa), added to the attire of divine beings, not as a large disc but as a floral and stylized part of their headgear. The reverse of Chola bronze Uma icons can be studied to understand the transformation of glowing light into ornate jewelry, adding in unique element of beauty and regalia to the iconography.

Not just in shape and style, halo in Indian art varied in the different powers and moods that it conveyed. While Nataraja, where Shiva is performing his Tandava, the dance of annihilation has a fiery aureole, Buddha who is the embodiment of tranquility and stillness is depicted with a gentler halo, simple or decorated with floral motifs, underlining the time and thought given by Indian artists and sculptors in developing the concept of halos and divine light and narrating it in visual mode.

Mughal Halos: Where Indian and European Lights Meet

Jahangir with a Golden Halo (Source: X, The Cultural Tutor)

”Nur-ud-din “the light of faith” is one of the titles of the Mughal ruler Shahjahan. Embracing the established Persian concept of Farr-i-Izadi (the brilliance or light of god) under which the king is the “brother of Sun and Moon” (Mackenthun 2009), the Mughal sovereigns expressed the principle of divine kingship through their miniatures, where behind the visages of the rulers a sun-like halo became a popular motif. Though many studies focus on the interaction between Christian missionaries and Mughal rulers as the moment of introduction of the halo in Mughal art, the preexistence of the motif in Indian art and the popularity of the concept in the Islamic world suggests that even though the idiom of Mughal miniatures derived from Christian halos, the deep roots of the idea and representation made it comfortable for the Mughal royal painters to include and experiment with the symbol. With the development of Mughal art, the halo transcended the sacred realm to become an element of royalty, a symbol of the exalted persona of the king, separating him from the rest of the world as a superhuman who glows because he experiences the divine light much closely than the rest of the humans. And do you know, the term “Tehzip” (Persian, Arabic, and Turkish) or “illumination” (filling with light) is the term used in Islamic culture for the art of illustrating manuscripts? Embellishing the artworks with gold, the Mughal artist succeeded in perfecting the art of illuminating, conveying the shimmer and grandeur of halos with golden brushstrokes.

Halos in Modern Art: A Study of Abanindranath Tagore’s Bharat Mata

The Illustrious and Lustrous “Bharat Mata” of Abanindranath Tagore (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

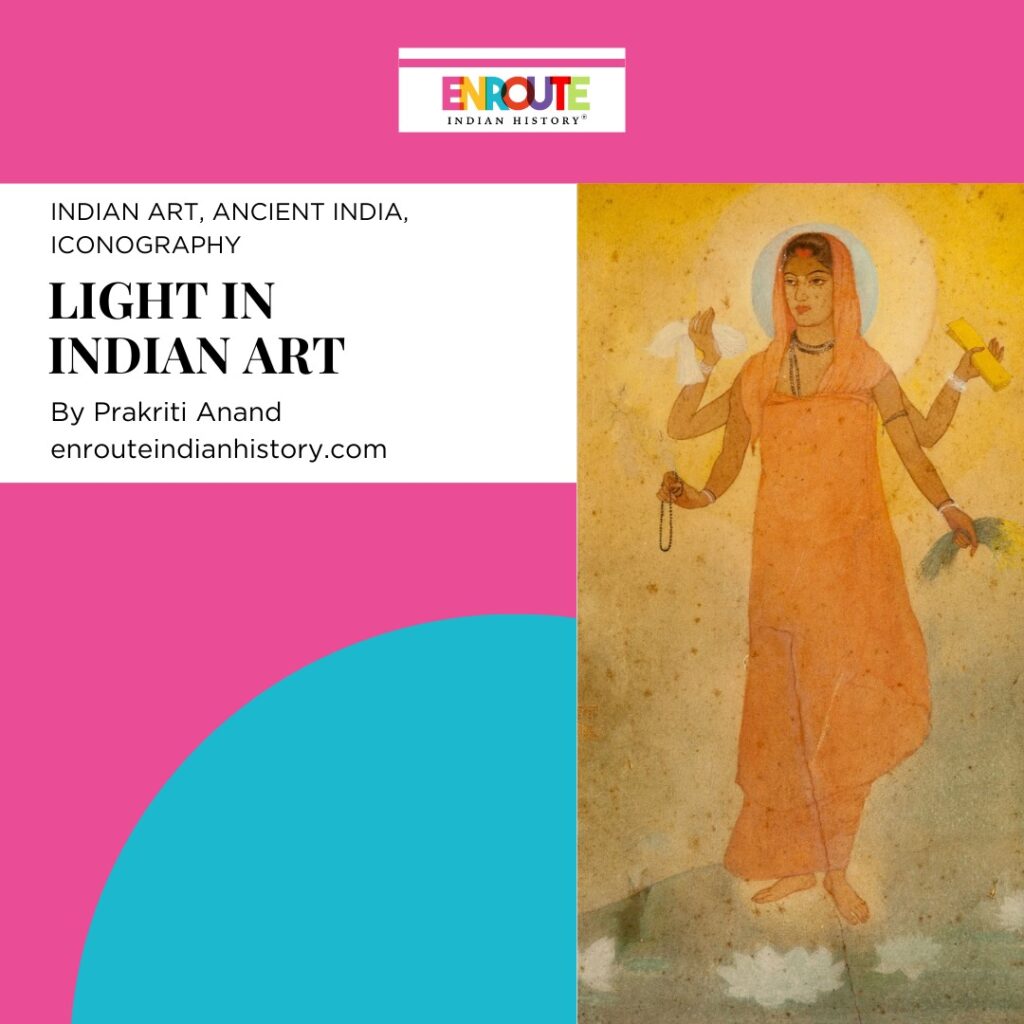

In the garb of an ascetic woman, the Bharat Mata of Abandindranath Tagore became a symbol of India’s movement for independence. Auster in all other aspects, Bharat Mata was made heavenly by Tagore’s use of a halo around her countenance, a soft yet striking circle of light, from which the space surrounding the goddess seems to be illuminated. Following a long trend of sculptors and painters who used the halo as a symbol of divinity, Abanidranath Tagore relied on the popularity of the halo or aura as a motif that resonated with the people of India, strengthening in them a reverence for mother India. While many hold the opinion that the halo in the artwork was derived from the Christian paintings of the Virgin Mary, studying the presence of the halo in Indian art and its continuity through the ages lets us comfortably conclude that Abanindranath was inspired by the glorious aura of auras in the indigenous art of the country.

World cultures believe that one of the first things to come into existence was light. It is believed to be the expression of creative and potent powers of the divine, that lights up the world as the Sun, Moon, and fire throughout different phases of the day. Before science could come up with a way to capture the luster of light in spaces (through the blub), art discovered and experimented with ways of representing light, a rich tradition that can be highlighted well in the study of Indian art. A peripheral but consistent presence in Indian aesthetics, halo or aura is a case of symbolism and a successful metamorphosis of light into matter. With this, like the radiant circle of light, our discussion comes to a full circle.

References

Chumak, Maria. 2020. “Influences of the East on Early Christian Iconography.” Open Journal for Studies in History, 11-24.

Johnston, E. H., trans. 2015. Buddhacharita of Asvaghosa. N.p.: Motilal Banarasi Das.

Kramrisch, Stella. 1988. The Presence of Siva. N.p.: Motilal Banarasidas.

Mackenthun, Tamara C. 2009. “CONTINUITY IN IRANIAN LEADERSHIP LEGITIMIZATION: FARR-I IZADI, SHI’ISM, AND VILAYET-I FAQIH.”

Sudhi, Padma. 1985. “SYMBOL OF ŚIRAŚCAKRA IN ART, RELIGION, AND PHILOSOPHY OF INDIA.” Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, 249-257.

- May 8, 2024

- 8 Min Read