Lights, Camera, Action – The Single Screen Cinemas of Delhi

- EIH User

- April 4, 2024

“Ye Dilli hai mere yaar, bas ishq, mohabbat, pyaar” – Delhi 6

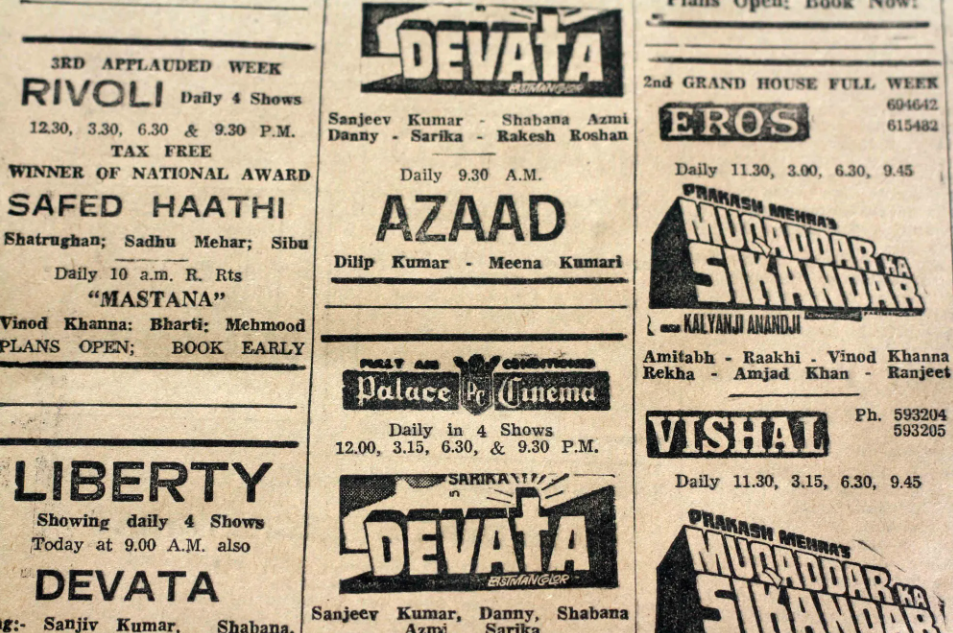

(Mayank Austen Soofi, The Delhi Walla – Cinema-listing in the Patriot newspaper dated 5 November 1978)

A multiplex theatre may be needed to screen the commercial blockbusters, but to screen those emotions, a single-screen cinema suffices. Some films transcend the confines of time, and so do some theatres. This is not just a tale of bricks and mortar; it’s a journey through the reels of time, where the silver screen reigns supreme. Delhi is not Delhi without its Dilliwale, and Cinema is not Cinema without its single screens.

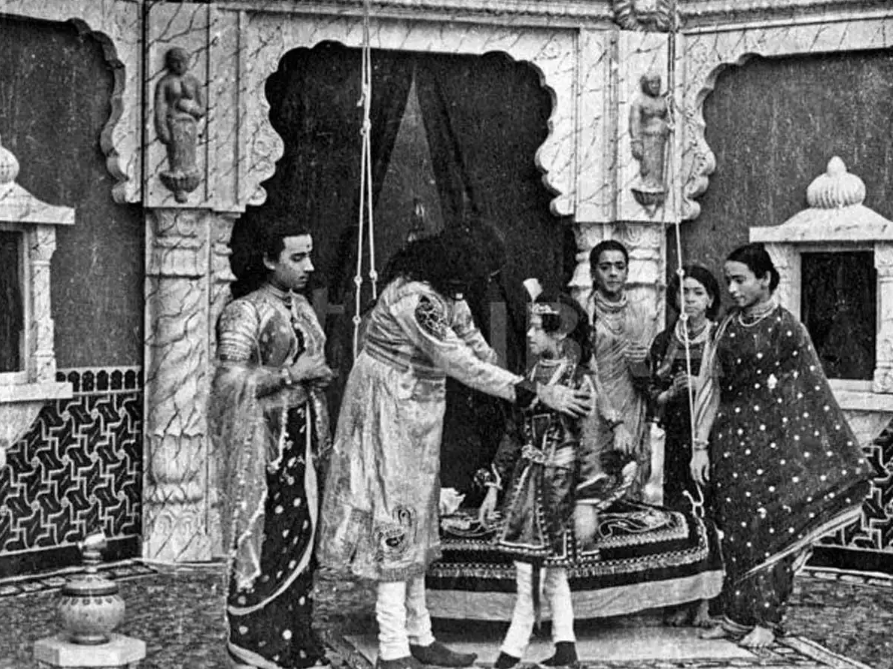

(Filmfare.com – A still from the first feature film ‘Raja Harishchandra’)

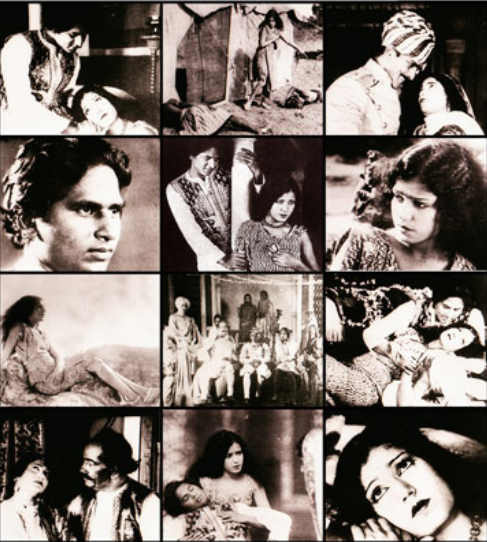

(Film Heritage Foundation – Stills from the first talkie ‘Alam Ara’)

Cinema has always been a major source of entertainment in the lives of Delhiites. But the evolution of this Cinema into what it is today has been a long journey since 1947. Rewinding the scene to July 1896, it was with the arrival of the Lumiere Brothers, Auguste, and Louis Lumière, that Cinema found its roots in India – one of the largest filmmaking countries in the world. Famed for inventing the cinematographe, a pioneering camera and projector device, they paved the way to set the foundations of motion pictures. As opposed to the kinetoscope – a peeping device, the cinematographe was rather revolutionary. The brothers came to Mumbai, where they previewed six silent short films (simply a series of visuals) to an elite British audience. The first Indian short film ‘The Wrestlers’ was made by Harishchandra Sakharam Bhatavdekar in 1899. However, the first full-length feature film was only made in 1913. Dundiraj Govinda Phalke, a magician, and an avid photographer turned filmmaker directed and produced ‘Raja Harishchandra’, a silent Marathi film with mythological influences based on the noble and truthful king Harishchandra. Regarded widely as the ‘Father of Indian Cinema’, Dadasaheb Phalke was a pioneer in the history of Indian Cinema.

It was only in 1931 that India’s first full-length sound film was released. Ardeshir Irani produced ‘Alam Ara’ – the first ‘talkie’. Talkie was a term initially employed for films that used speech and sound. However, it eventually became synonymous with theatres and so, theatres also came to be known as talkies.

Initially, cinemas were displayed in tents, the first being in 1907. The earliest cinema halls were set up in places where the British population resided. Consequently, Delhi was a late bloomer owing to the unstable socio-political climate it has been subjected to throughout history. Filmmaking was also largely supported by the local population in other places but the scenario in Delhi was riddled with migrants amongst intense political activity. The Single Screen Cinemas in Delhi flourished and began with the shifting of the British Capital to Delhi from Kolkata. These popped up in the 1920s and 1930s, in the old walled city of Shahjanabad and the newly constructed Connaught Place.

(Mayank Austen Soofi, The Delhi Walla – The ticket window at the Jagat Cinema)

Nestled within Delhi’s cinematic odyssey is the issue of class and social differentiation pertaining to the dynamics of public space in cinemas. Recent research on Delhi’s cinema history reveals that significant changes occurred after World War II and the Partition, where there was an interchange of population. The population of Muslims in Shahjanabad dwindled significantly after the partition. Moti Cinema, opened in Chandani Chowk in 1938,

screened the notable Hindi films of the era, starting with the renowned productions of Prabhat Talkies, and Bombay Talkies while transitioning to the acclaimed works of esteemed filmmakers from the 1950s like Raj Kapoor, Bimal Roy, Mehboob Khan, and Guru Dutt. It catered to an upscale crowd and even showed English films in morning screenings until the mid-1970s.

In contrast, Jagat Cinema was also located in the same area but despite showcasing similar films, catered to a poorer section of the old city. Referred to as the “Macchliwallon ka Talkies”, it was closer to the fish market and chicken markets near the Jama Masjid. Nevertheless, Jagat Cinema enjoyed its fair share of audience and grandeur. Film historian and author Ziya Us Salam in his book Delhi 4 Shows: Talkies of Yesteryear, shared an anecdote about a poetically inclined resident of the nearby Matia Mahal neighborhood who would come to see Meena Kumari’s Pakeeza every day for the six months that it was screened. The entire party, consisting of his family, would wait for the song, Chalte Chalte, and then leave the theatre. Changing tides, however, the Moti Cinema in recent years was forced to screen only Bhojpuri movies which attracted the migrant daily wage laborers. Jagat stopped screening films in 2004.

(The Pioneer – the Ritz Cinema in all its glory)

Adjacent to ISBT is another epitome of cinematic glamour, the Ritz Cinema. Starting as the Capital Cinema in 1932, it was renamed Ritz almost a decade later in 1942 with the screening of PC Barua’s Jawan. Ritz provided private boxes catering to a family audience, drawing crowds from far and wide to enjoy A-grade Hindi films. Notably, women from Old Delhi, who were traditionally discouraged from attending films alone, found a solution in the 1950s and ’70s. Instead of watching movies at nearby theaters, they devised a clever workaround: gathering in groups at Purdah Bagh near Daryaganj and then traveling together to the Ritz. Seats were reserved exclusively for women. Ritz has now closed its operations after it was sealed in 2016 for non-payment of property tax.

(The Indian Express – A shot of the Regal Cinema from the lanes of Connaught Place)

In the midst of Central and South Delhi stand numerous single-screen cinemas with the remnants of a bygone era that still hold sway over the city’s cultural landscape. Regal Cinema, a cine monument, began its operations in 1932 in Connaught Place. Constructed by architect Walter Sykes George, with an art deco facade, grand stairway, and exclusive boxes; it served the elite Delhiites as a place for all things entertainment. Be it ballets, plays, or films. After its inauguration, Regal Cinema soon became the preferred venue for premieres, screenings, and cultural events, attracting notable personalities like Prithvi Raj Kapoor and Raj Kapoor from the world of cinema and beyond. It was witness to a culturally significant moment in Delhi’s queer activism history when it emerged from the underground in 1998. Facing backlash from right-wing groups, Deepa Mehta’s Fire, a narrative depicting the journey of two women embracing queer love, sparked controversy. While opposers tore down posters and broke glass panes, Director Deepa Mehta held a candlelight vigil outside the Regal Cinema building in defense of her film Fire. Despite witnessing the evolution of Delhi’s cultural landscape while remaining a symbol of the city’s cinematic heritage, Regal shut down in 2017. The curtains closed and the lights went out with Raj Kapoor’s iconic films – Mera Naam Joker and Sangam.

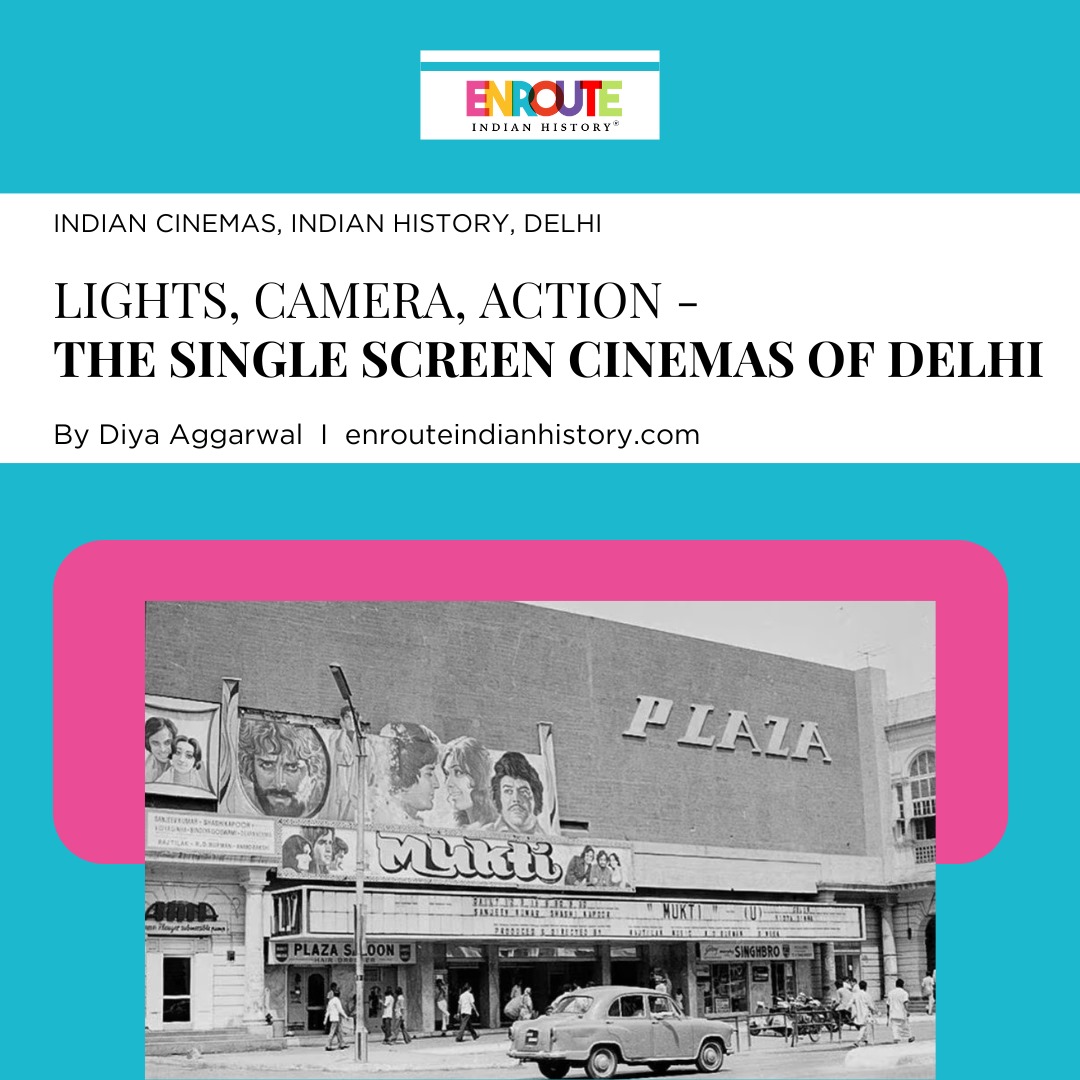

(KK Chawla, HT Photo – Plaza Cinema in 1977)

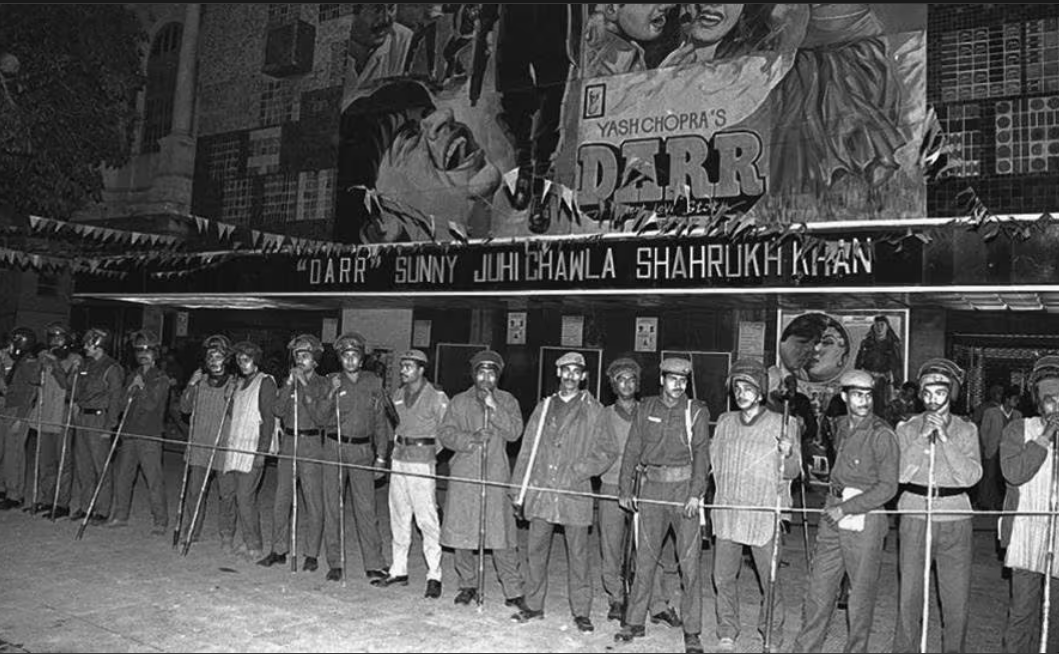

(Rajiv Gupta, HT Photo – Policemen blocking the Odeon after a blast in 1994)

A quartet was formed by the Regal, Plaza, Rivoli, and Odeon Cinema in Connaught Place. Designed by Robert Tor Russell and owned by Director and actor Sohrab Modi in the earlier days, the Plaza boasted a two-story foyer adorned with velvet curtains and a majestic chandelier suspended above the hall. Its ambiance was one of the reasons why Plaza rose to fame. It started with an imported Century Projector, one of the best in those days. Rivoli was the smallest among the lot, built in the 1930s. The hall featured minimalist architecture, reflecting Western aesthetics, with interiors characterized by a striking blend of black and white marble. During the 1960s, Rivoli stood out as one of the few fully air-conditioned theaters in New Delhi. Both the Plaza and the Rivoli Cinema were known for screening Hollywood blockbusters.

The last of the quartet, the Odeon, completed in 1939, was also the brainchild of British architect Tor Russell, fashioned in an elegant opera house style. Initially owned by prominent builder Sobha Singh until 1953, the theater swiftly became a cornerstone. In a significant development in 1963, a balcony was added to the hall, reserved exclusively for film stars, foreign diplomats, and political dignitaries, further enhancing the theater’s prestige and allure. It stood out as an exception among the quartet catering to both Indian and Western audiences. The historic Plaza and Rivoli cinemas, once stalwarts of Delhi’s entertainment scene, embarked on a new journey through a joint venture with multiplex giant PVR Cinemas. Odeon also joined hands with Reliance Big Cinemas.

The fading importance of single screens in Delhi reflects the relentless march of progress in the entertainment industry. With the multiplexes offering modern amenities and a huge range of viewing options, traditional theatres have struggled to retain their relevance. However, now, they leave behind a legacy of nostalgia and cultural renaissance that will forever be etched in the memories of Delhiites. Their era may have been drawn to a close, but their contributions to the city’s cinematic heritage remain timeless.

Citations

- Chahar, A. (2019). The Story of Delhi’s Cinema Halls. [online] Peepultree.world.

- Rana, P. and Garia, N. (2011). New Delhi’s Heritage Cinemas. WSJ. [online]

- Vemulakonda, S.S. (2015). GROWTH OF MULTIPLEX AND ITS IMPACT – AN INDIAN CINEMA EXPERIENCE. www.academia.edu. [online]

- Vasudevan, R. (2003). Cinema in urban space. Seminar. [online]

- Soofi, M.A. (2020). Delhiwale: On walking past Old Delhi’s iconic Gali Jagat Cinema Wali. [online] Hindustan Times.

- Nair, M. (2017). A farewell to Delhi’s Regal Cinema, the birthplace of the city’s LGBTQ movement. [online] Scroll.in.

- Dastidar, A.G. (2011). The Delhi show, on since 1930s. [online] Hindustan Times.

- Salam, Z.U. (2016). What Delhi has lost with the closure of the Ritz cinema. [online] Scroll.in.