Article by EIH Researcher and Writer

Anupam Tripathi

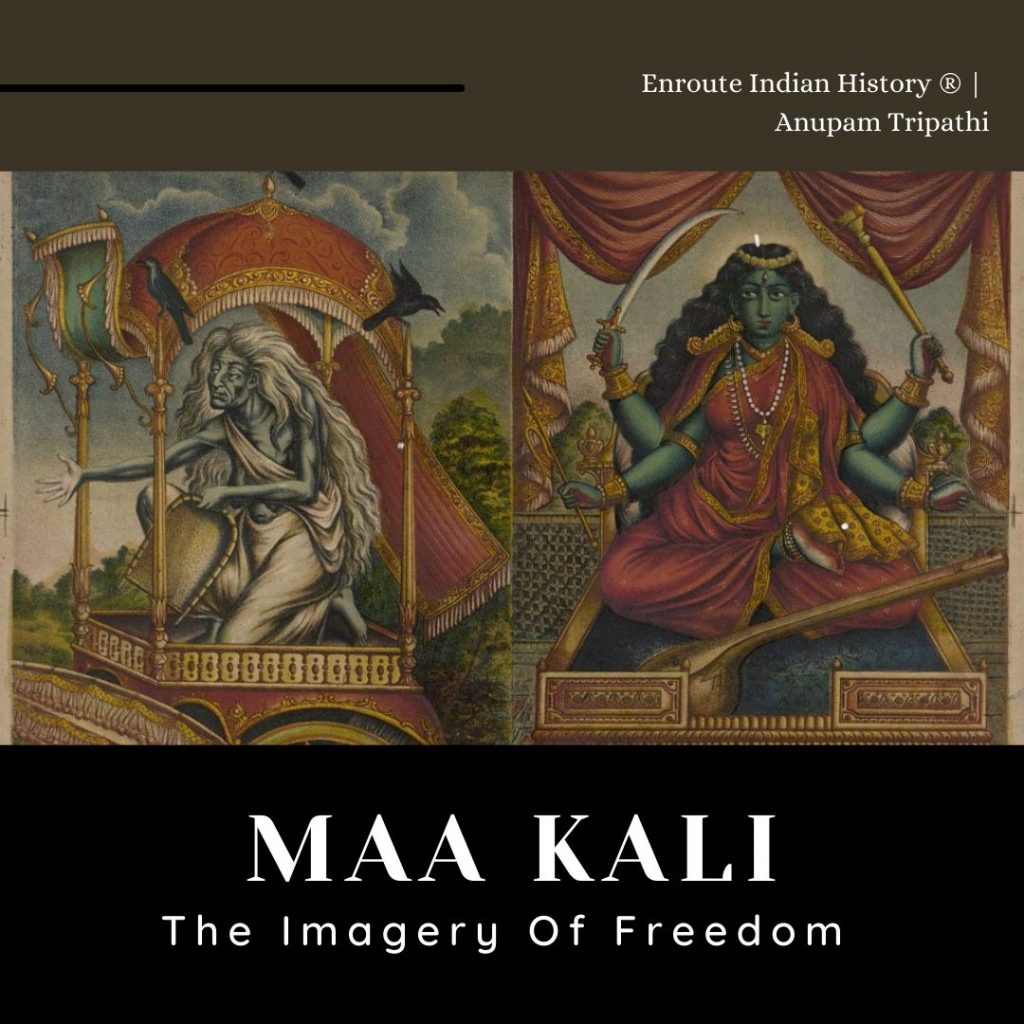

Orientalists understood “tantra” as a mere sexual practice, citing its origins as a philosophy that influenced Hinduism and Buddhism in medieval India. The term “tantra” derives from the Sanskrit verbal root “tan” (meaning “to weave”); in Hinduism, “tantra” refers to the dialogue between god and goddess. In the realm of tantra, the central theme is divine energy and creative power (shakti) represented by the feminine aspect of one of several gods; personified as Devi or Goddess, she is also represented as Shiva’s wife. Tantric texts usually take the form of a dialogue between Shiva and Shakti. Kali or Kalika is one of the many forms of Shakti, the name and form of which makes the particular correspond to the aspect that the god takes on, like Kala and Kali, Bhairava and Bhairavi. According to traditions dating back to pre-Vedic times, Kali was born from the third eye of Goddess Durga as a destructive and terrifying manifestation of female power sent to wreak havoc on the forces of evil. Throughout India to this day, Kali is revered as the destroyer of evils, able to free her devotees from unjust rule and submission. Ma (Mother) Kali has many forms, such as that of a mother and a warrior. She became a symbol of revolution in the 19th century Bengal. Kali means resistance. In our case, this resistance was against patriarchy and white supremacy.

In the East India, Bengal was the epicentre of British colonial rule from 1757, as well as one of the earliest places of tantric practice. Kali embodied the cosmic connectedness of creation and destruction. Since the beginning of the 19th century, British missionaries and imperialists in India have fantasized about tantra, and in particular the Kali cult, as a corrupt cult of violence and ecstasy that justified its civilizational presence. Indians took advantage of this, using the idea of kali to express their anti- colonial sentiments. The widow goddess Dhumavati was employed as a sad representation of India as a “beggar mother” (Bharat Bhiksha), toothless and emaciated, devastated by the periodic famines inflicted on the nation by British economic policies. This was one of the many visual means undertaken to reimagine the motherland. In 1907, the advertisement for Swadeshi ‘Kali Cigarettes’, published by Calcutta Arts Studio at a time of political instability, caused further unease in the Britain.

Herbert Hope Risley was particularly anxious that Kali appeared to be adorned with European heads, and it was such imagery that prompted him to draft the Press Act of 1910, threatening eruptions of tantric terrorism. Guided by the political theology of Bengali thinker Aurobindo Ghose (1872–1950), many organized underground secret societies posing as revolutionary sanyasis (ascetics) and performing esoteric initiation rites before Kali idols at cremation grounds while vowing to risk their lives for the homeland liberation. Revolutionary pamphlets legitimized violence in the general public. It conjured up the bloodthirsty appetites of Ma Kali and her desire to sacrifice “white goats”, a coded reference to the English. While guns were hard to come by, explosives were made from scratch, “Ma Kali Bomb” (Mother Kali Bomb) a more democratic way of breaking free from oppressive British rule. The image of Kali standing on Shiva was used as the cover of James Campbell Ker’s Political Trouble in India, 1907-1917, a confidential account of the rise of the revolutionary movement. Indian revolutionaries in the early 20th century capitalized on British fears and used tantric imagery to express nationalist ideals and terrorist violence. But at the same time, the discourse around tantra also became a key element in the conceptualization of India and “Hinduism”.

Reference:

- Hugh Urban, Tantra: Sex, Secrecy, Politics, and Power in the Study of Religion.

- Daniel Odier, Tantric Kali.

- https://www.varsity.co.uk/arts/20453

- https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&url=https://blog.britishmuseum.org/kali-rises-in-the-east/&ved=2ahUKEwiX4dfNy-D2AhXcIbcAHfB_AfoQFnoECB0QAQ&usg=AOvVaw1aUPVmvdidhe25qEQRUcej

- https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&url=https://www.worldhistory.org/Kali/&ved=2ahUKEwiX4dfNy-D2AhXcIbcAHfB_AfoQFnoECB8QAQ&usg=AOvVaw1cF61677nnrCotRuhVceHT

- https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&url=https://amp.scroll.in/article/855283/could-the-western-world-be-completely-wrong-in-thinking-kali-is-a-demonised-goddess-in-india&ved=2ahUKEwiX4dfNy-D2AhXcIbcAHfB_AfoQFnoECBwQAQ&usg=AOvVaw11nCewD-XkdvSX6vKStj0e