Sacred Space is a portion of earth’s space, recognized by individuals or groups as worthy of devotion, loyalty or esteem. The sanctity of a sacred space is assigned, defined, limited and characterized by human culture, experience and goals. There are three broad categories of sacred space: mystic-religious spaces associated with religious or other experiences inexplicable through conventional means, Homelands representing the roots of each individual, family or people, and Historical sacred spaces representing sites which have been assigned sanctity as a result of an event occurring there. Mystico-religious spaces serve as points where man can communicate with his god or gods. They facilitate access to supernatural power. Some examples which serve as the focus of such mystic-religious sacred spaces are temples, shrines, cathedrals, sacred groves, mountains or trees. Architectonic constructions, such as monasteries are one such example of mystic-religious sacred spaces.

The phenomenon of Buddhism is divided into seven major dimensions. It is said to have a practical and ritual dimension; an experiential and emotional dimension; a narrative or mythic dimension; a doctrinal and philosophical dimension; an ethical and legal dimension; a social and institutional dimension; and a material dimension. The material dimension is about objects in which the spirit of a religion becomes incarnate, such as churches, temples, and works of art, statues, sacred sites, and holy places like pilgrimage sites. Monasteries are such definite examples of the material dimension of Buddhism.

The popularity of Gautam Buddha compelled the wealthy patrons as well as the kings to establish residential centers where monks could remain for some parts of the year. These residences evolved into permanent institutions known as viharas or monasteries. Viharas, literally means “dwelling”. The term originated when monks and nuns used to wander through the countryside, settling down only during the rainy season, the term was used to designate an individual hut within the rainy season retreat. Later on, with the establishment of permanent dwellings for the monks, the term came to imply an entire monastery.

A monastery contains a courtyard leading to the principle shrine, often placed within an assembly hall. This hall sees the monks (or, in some cases, lay practitioners) gather as required by the regular ritual cycle, or for services necessitated by special circumstances (for instance, for funerals). In a small monastery, there may be room for only a few to assemble, while in larger monasteries the congregation may number several thousand, seated in strict accordance with rank and ritual order. Some of these protocols are according to the stipulations found in the Vinaya, but above all on established customs within Tibetan monastic communities, as specified within the monastic charters (chayik).

The defining element of a monastery is the vihara. The monastery houses the sangha (a community of monks and nuns), which constructed stupas (burial tumuli) – both within chaityas (apsidal halls) and as freestanding structures—adjacent to their viharas. Tibetan stupas were dedicated to the great events from the life of Gautam Buddha, such as his Nativity and Nirvana.

The chief function of the monastery was ritualistic grooming of young novices and protection of the community, including rulers and subjects. Young doors were expected to memorize the invocations of buddhas, bodhisattvas and the teachers of one’s lineage.

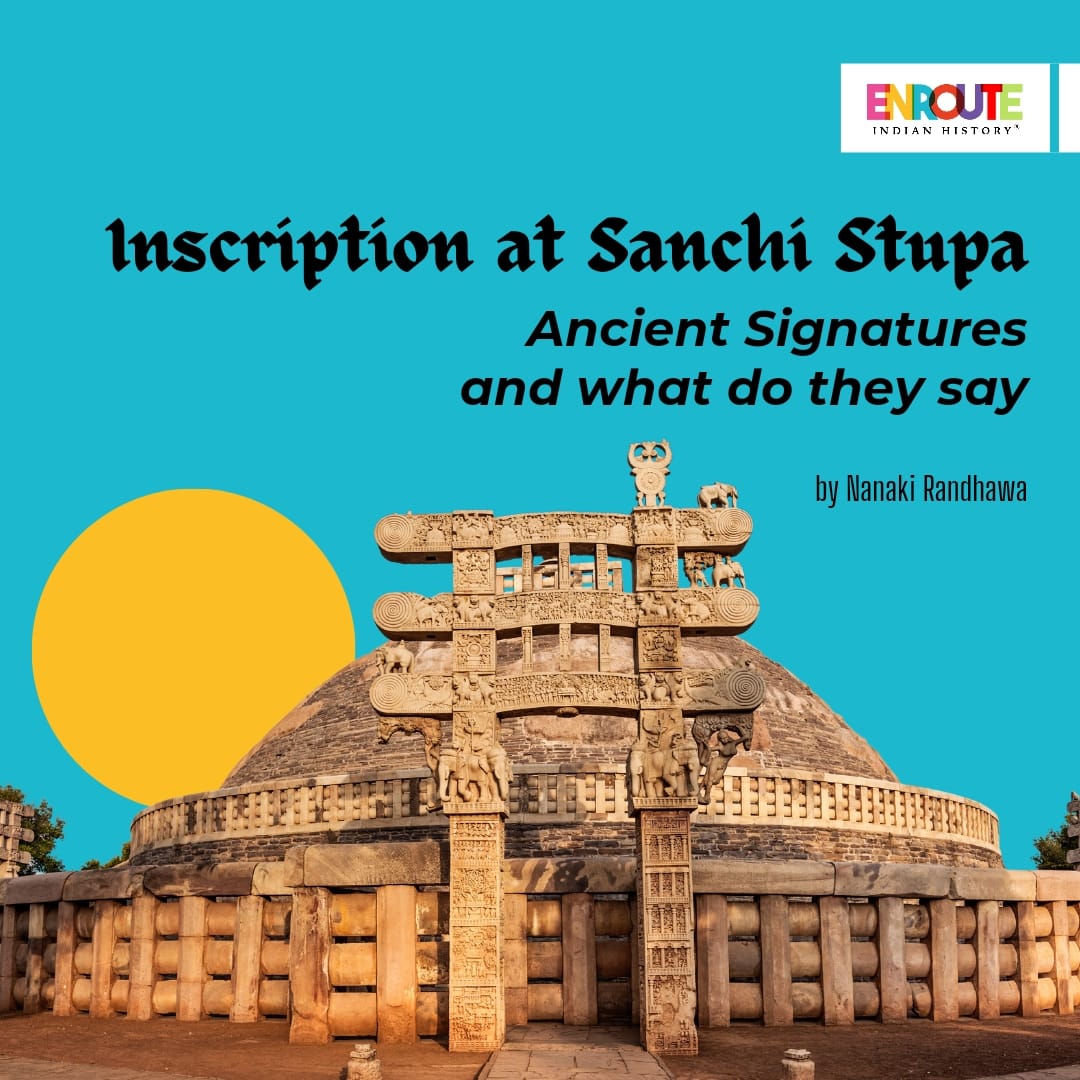

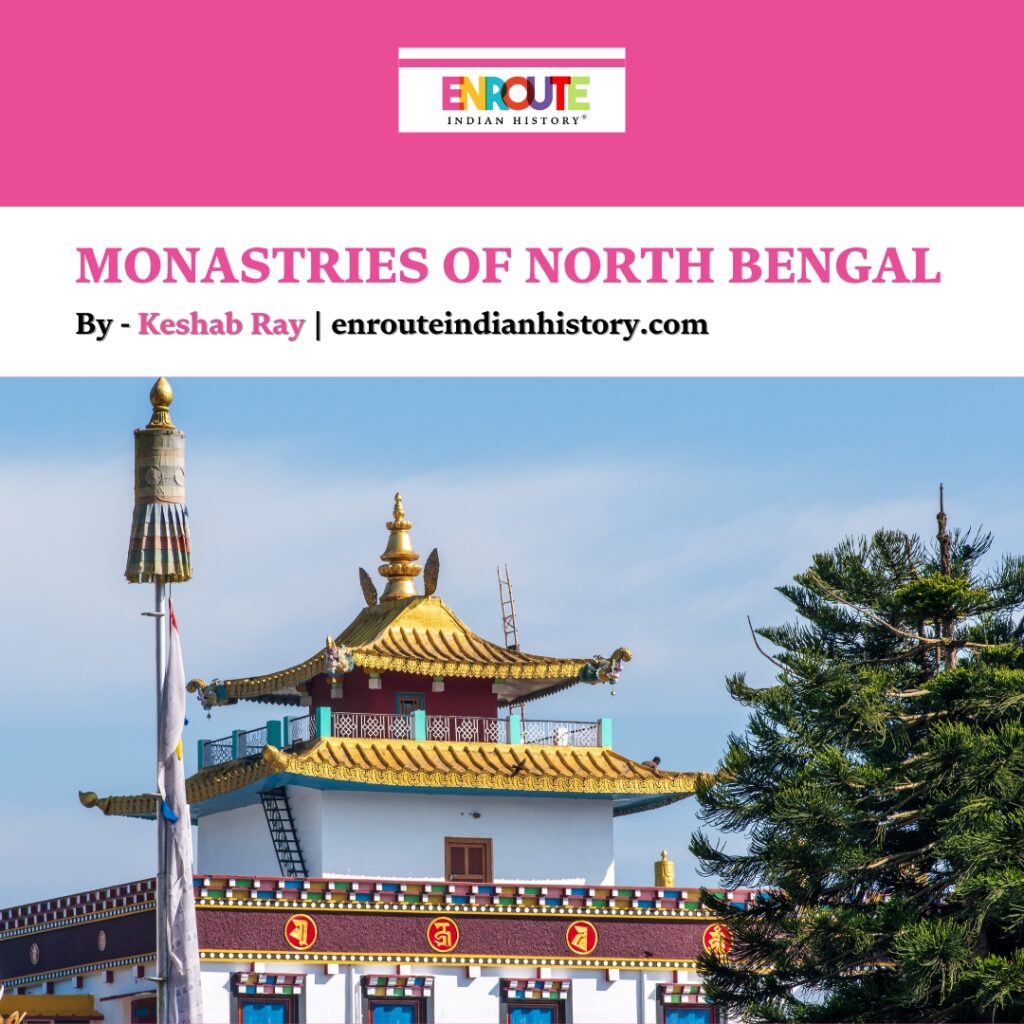

Tibetan Buddhist Monasteries

During the 7th Century AD, a very strong king in Tibet called Songtsen Gampo, sent a group of seven Tibetans to India to see whether Tibetans could become monks. After they returned, Buddhism was inaugurated in Tibet. There is a presence of four main sects in Tibetan Buddhism, namely the Nyingma, Kagyu, Sakya and the Geluk. After thirteenth century, monasteries sprung up all over Tibet. Shifting to their diaspora into India, Tibetan refugees have built hundreds of permanent Buddhist monasteries throughout the subcontinent in most of their new settlements. These include Ladakh, Lahul and Spiti, Sikkim, the Darjeeling Hills and parts of Arunachal Pradesh in India, parts of Northern Nepal, and the independent state of Bhutan.

Tibetan Buddhism structures society and the individual agent through the order it imposes upon space and time. The spatial ordering of monastery and the temporal ordering of observances within it exemplify Buddhism’s role in forming Tibetan experiences and orientations. A Buddhist monastery consists of ‘the stūpa, the chaitya worship hall containing a stūpa, and the vihāra or the retreat/dwelling’.

Sacred Spaces have interconnectedness to religion, identity, and attachment. Sacred Spaces have attachment to natural landscapes, and this includes rivers, lakes, trees, mountains and other natural elements that are sacralized and revered. Mountain peaks have been regarded as the abode of Gods and ancestors. Tibetan Buddhist Monasteries of Bengal are located atop peaks of high mountains.

Indian Buddhism was practiced at Nalanda and other contemporary institutions in Bengal and Bihar, Tibetan Buddhism begun in the Darjeeling and Jalpaiguri districts of northern West Bengal. It was strengthened by the influx of Tibetan refugees. These Tibetan Buddhists peopled in the major towns of Darjeeling, Ghoom, Kalimpong, Kurseong, Tindharia.

Scholar D.C. Ahir lists the Viharas and monasteries at North Bengal are: Ghoom Monastery; Bhotia Basti Monastery; Thubten Sangag Choeling Monastery, West Point; Dromo Dongkar Monastery; Guru Lhakhang; Du Chu Monastery; Mem Monastery; Gandhamadan Vihara, Chota Kagjhora; Ananda Vihara, Sonada. Some other Viharas in Darjeeling district are: Triyana Vardhana Vihara, Kalimpong; Dharmodaya Vihara Kalimpong; Tharpa Choling Monastery Kalimpong; Sangdo Peri, Kalimpong Dongser Gon Sum Monastery, Kalimpong; Buddha Vihara, Sevoke Road, Siliguri; Buddha Vihara, Kuresong; Buddha Vihara, Pradhan Nagar, Siliguri.

Famous Monasteries of Kalimpong District

- Kagyu Thekchen Ling Monastery

Karma Lodrö Chökyi Senge (1954–1992), the 3rd Jamgon Kongtrul Rinpoche, provided four-acre site to the 4,000-odd Buddhist devotes on the 15th day of the 1st Tibetan month of the Fire Hare year, 1987, and agreed to the community’s request to establish a monastery there to support and preserve the religious tradition and culture of the people. Work started in April 1988 and Kagyu Thekchen Ling opened on June 6th, 1990, the great auspicious day of Cho Khor Du Chen, the day the Buddha first turned the Wheel of Dharma.

Kagyu Thekchen Ling Lava Monastery

- Gaden Tharpa Choling Monastery

The construction of the oldest monastery in Kalimpong begin on the 1st day of the 11th month, 1912 of the Tibetan Calendar, when the very first piece of land for the erection of the Gaden Tharpa Choling Monastery was first donated by Aunt Thinley Gyalmo and her husband Baba Lulu. It was founded in 1922.

Gaden Tharpa Choling Monastery

- Zang Dhok Palri Phodang Monastery

Zang Dhok Palri Phodang Monastery was located at the Durpin Dara Hill, established in 1946 by Hon. Dudjum Rimpoche.

Zang Dhok Palri Phodang Monastery

Famous Monasteries of Darjeeling

- Yiga Choeling Monastery

The monastery belongs to the school of Gelugpa, based on the teachings of Tsongkhapa, who emphasized the need to follow the monastic ethical code taught by Buddha, known as Vinaya.

Yiga Choeling Monastery

- Sangchen Thongdrol Ling Monastery/ Ging Gompa

Relocated after the complaint of British residents, the the Ging Monastery, this is a branch of the Pemayangtse Monastery.

Sangchen Thongdrol Ling Monastery

- Mag-Dhog Yolmowa Monastery

The construction of this monastery started in 1914, same year as World War I, thus keeping the war in mind, the monastery was named ‘Mag-Dhog”, meaning ‘to do away with war’.

Mag-Dhog Yolmowa Monastery

- Karma Dorjee Chyoling monastery

An important monastery of the Karma Kagyu sect was Phodong, in the North District of Sikkim. The religious name of the monastery is Karma Tashi Choekhorlling. Initially there was a meditation hermitage or tsamkhang, and in the year 1723, during the reign of Chogyal Gyurmed Namgyal, construction of a monastery was started at the spot. But, unfortunately, Chogyal died in 1734. However, the monastery was completed in 1740 with the support of devotees. During the reign of Chogyal Tsugphud Namgyal (1793-1863), the old monastery was dismembered, and a new monastery was constructed in its place. A branch of this monastery was constructed in Darjeeling named Karma Dorjee Choelling in the year 1765. The place Darjeeling derives its name from this monastery as this monastery was attributed to a renowned Terton named Dorjee Lingpa. Located in an area called Mahakal or a rocky hill, it had to shift from the original place to another site called Bhutia Busty in 1878 as the British claimed that the noise created by the rituals of this monastery is disturbing the sanctity of their Church which was situated below that monastery. In 1979, the present Karma Dorjee Chyoling monastery was built in Bhutia Busty.

Karma Dorjee Chyoling monastery

- Pokhriabong Lepcha Monastery

It is situated in a village called Pokhriabong, in the Jorebunglow Sukhiapokri CD block in the Darjeeling Sadar subdivision of the Darjeeling district in West Bengal, India.

Pokhriabong Lepcha Monastery

Legacy

The birth of Buddhism in the subcontinent and its return in a new different way shows the circular flow of the religion. They conceptualized, materialized, and authentically developed an idea of a sacred pace. The impactful influence of Tibetan Buddhism and resulted in the formation of various monasteries in North Bengal. The Buddhist monasteries primarily were either based in Darjeeling and or in Kalimpong. The monasteries radically pushed and aggressive promoted learning, learning, and art.

Bibliography

- Ahir, D. C. Buddhism in Modern India. 1991.

- Bapat, P. V. 2500 Years of Buddhism. Publications Division Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, 1954.

- Bhutia, Gnudup Sangmo. “Monastic Land Holding System in Sikkim (1642-1975).” Thesis Submitted To Sikkim University, 2022, dspace.cus.ac.in/jspui/bitstream/1/7760/1/Gnudup%20Sangmo%20Bhutia-History-PhD.pdf.

- Denzongpa. “Ging Gonpa.” Wikimedia, 19 Oct. 2015, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ging_Gonpa,_presumably_the_oldest_monastery_in_Darjeeling.JPG.

- Desal, Tenzin, editor. “Tibet Policy Journal.” Tibet Policy Journal, illustrated by Tsering Samdup, vol. X–X, 2, Tibet Policy Institute, Nov. 2023, tibetpolicy.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/2023-TPI-English-Journal-Final.pdf#page=97.

- Eckel, Malcolm David. Great World Religions: Course Guidebook. Buddhism. 2003.

- Fogelin, Lars. An Archaeological History of Indian Buddhism. Oxford UP, USA, 2015.

- Gagnon, Bernard. “Yiga Choeling Monastery, Ghum, India.” Wikimedia, 15 May 2018, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Yiga_Choeling_Monastery,_Ghum_02.jpg.

- —. “Zang Dhok Palri Phodang, Kalimpong, India.” Wikimedia, 17 May 2018, upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b7/Zang_Dhok_Palri_Phodang_01.jpg.

- Gupta, Amitabha. “Bhutia Busty monastery or Karma Dorjee Chyoling monastery.” Wikimedia, 5 May 2023, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bhutia_Busty_monastery_or_Karma_Dorjee_Chyoling_monastery_01.jpg.

- —. “Geden Tharpa Choling Monastery premises , Kalimpong.” Wikimedia, 13 May 2023, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Geden_Tharpa_Choling_Monastery_premises_,_Kalimpong_01.jpg.

- Harvey, Peter. An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices. Cambridge UP, 2013.

- Huber, Toni. The Holy Land Reborn: Pilgrimage and the Tibetan Reinvention of Buddhist India. University of Chicago Press, 2008.

- Jackson, Richard H., and Roger Henrie. “Perception of Sacred Space.” Journal of Cultural Geography, vol. 3, no. 2, Mar. 1983, pp. 94–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/08873638309478598.

- Jamgon Kongtrul Labrang. jamgonkongtrul.org/section.php?s1=2&s2=2.

- Joydeep. “Kagyu Thekchen Ling Lava Monastery, Photographed at Lava, West Bengal, India.” Wikimedia, 3 Dec. 2019, upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/46/Kagyu_Thekchen_Ling_Lava_Monastery%2C_Lava%2C_West_Bengal%2C_India.jpg.

- Kapstein, Matthew. Tibetan Buddhism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford UP, 2014.

- Kayal, Soumen. “Heritage of Buddhist Monasteries in Kalimpong District, West Bengal.” Retrospect, no. New Series-I, Dec. 2023, www.researchgate.net/profile/Indrachapa-Gunasekara/publication/378567185_Utilization_of_Technology_in_Heritage_Tourism_with_Special_Reference_to_Sigiriya_World_Heritage_Site_Sri_Lanka/links/65e04bfde7670d36abe618e4/Utilization-of-Technology-in-Heritage-Tourism-with-Special-Reference-to-Sigiriya-World-Heritage-Site-Sri-Lanka.pdf#page=2.00.

- Keown, Damien. A Dictionary of Buddhism. OUP Oxford, 2004.

- —. Buddhism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford UP, 2013, https://doi.org/10.1093/actrade/9780199663835.001.0001.

- Mazumdar, Shampa, and Sanjoy Mazumdar. “Sacred Space and Place Attachment.” Journal of Environmental Psychology, vol. 13, no. 3, Sept. 1993, pp. 231–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0272-4944(05)80175-6.

- “North Bengal.” Vanya Awas, vanyaawas.com/images/North-Bengal-Tourism_Brochure.pdf.

- Ober, Douglas. Dust on the Throne: The Search for Buddhism in Modern India. Stanford UP, 2023.

- Powers, John. Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism. Shambhala Publications, 2007.

- Prasad, Birendra Nath. Archaeology of Religion in South Asia: Buddhist, Brahmanical and Jaina Religious Centres in Bihar and Bengal, c. AD 600–1200. Taylor and Francis, 2021.

- Raj, Richa, *, et al. “Buddhism in Sikkim: A Study in Cultural Syncretism.” DU Journal of Undergraduate Research and Innovation, journal-article, journals.du.ac.in/ugresearch/pdf/Richa%20Raj%2018.pdf.

- Rajesh, M. N., and Thomas L. Kelly. The Buddhist Monastery. Roli Books Private Limited, 1998.

- Rao, Ursula and Mircea Eliade. Sacred Space. Edited by Hilary Callan, John Wiley and Sons, Ltd., 2018, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118924396.wbiea1713.

- Rowland, Benjamin. The Art and Architecture of India: Buddhist, Hindu, Jain. Puffin Books, 1977.

- Sarai, Sumit. “Mag-Dhog Yolmowa Monastery or Aloobari Monastery.” Wikimedia, 3 May 2016, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Aloobari_Monastery_Full_Front_View.jpg.

- WANGCHUK, PEMA. “S. MAHINDA THERO: THE SIKKIMESE WHO GAVE LANKANS THEIR FREEDOM SONG.” BULLETIN OF TIBETOLOGY, vol. 139, 2021, pp. 139–41. archivenepal.s3.amazonaws.com/digitalhimalaya/collections/journals/bot/pdf/bot_2008_01-02_06.pdf.

- Ydl9903562552. “Lepcha Buddhist Monastery.” Wikimedia, 11 May 2019, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pokhriabong_Lepcha_Monastery_Terda_Pema_Lingpa_Lepcha_Community_Gumpa.jpg.

- March 1, 2024

- 11 Min Read

- August 12, 2023

- 9 Min Read

- August 12, 2023

- 8 Min Read