Multifaceted Ramayana: The SouthEast Asian history of masks in Ramayana plays

- iamanoushkajain

- June 14, 2025

By Juhi Mathur

According to Nigerian playwright and critic Inih A. Ebong, masks in theatrical settings are charismatic devices, sui generis (in Latin meaning unique), whether in its magical, religious, ritualistic, socio-political form or artistic application and conception. It commands attention in an auditorium, possesses its own form, and has a consciousness and an inherent essence. Masks have widely been used in various ritualistic practices and folk plays since time immemorial, whether in Africa for shamanistic purposes or in street plays by children as they enact stories from Hindu epics and legends. They have their own rich history and heritage, and they have been an intricate part of the storytelling, transporting the audience to a different world altogether, and inciting visceral reactions and encouraging an introspective analysis of varied themes that govern the human condition.

When it comes to narrative storytelling, India is known for its puranic and Vedic stories which are gripped with moral lessons, adventures, and themes of heroism – namely the epics of Ramayana and Mahabharata that have been part of Indian socio-political culture as well as inspire various religious beliefs and practices even to this day. These stories fuel the creativity of the human mind, which has led to the production of different iterations and re-enactments of these legends throughout history in India as well as other regions of southeast Asia.

Text of Ramayana

The epic of Ramayana is one of two major ancient Indian epics, attributed to sage Valmiki, written in Sanskrit in the 3rd century BCE, it is considered to be a smriti text, belonging to the genre of itihasa, as it textually illustrates the history of Indian subcontinent whilst encouraging the reader to imbue valuable life lessons from it. Ramayana has twenty-four thousand shlokas which are divided into five kanda, delineating the story of Lord Rama, the prince of Ayodhya, who is the seventh avatar of Lord Vishnu. The story is about Ram’s fourteen-year exile along with his wife Sita and brother Laxmana, Sita’s kidnapping by Ravana, Rama’s journey to Lanka, Ram’s army of monkeys, the war between Rama and Ravana, and Ram’s triumphant return and crowning in Ayodhya. The epic is woven into the cultural and religious tapestry of the Indian subcontinent, mainly Hinduism and it has gained religious and cultural relevance in Buddhism and Jainism too. There are different versions of Ramayana in different countries across southeast Asia Namely – Thailand (Ramakien), Cambodia (Reamker), Nepal, Tibet, Burma, and Indonesia amongst many others.

Different forms of Ramayana masks in India

Ramayana itself is a textual resource which has found its place in visual vocabularies with various illustrated versions of Ramayana, and since it is in a shloka format, it has been performed since ancient times and has become an integral part of folk theatre as well as modern theatrical productions. The epic is performed, re-envisioned, and recontextualised as per the evolving times, it is akin to celebrating the victory of good over evil, and the performance becomes a way of transmitting these values and ideas. In theatrical settings, plays based on Ramayana employ every tactic and available tool to bring the stories to life and this is achieved through the sets, costumes, adornments and sometimes, if not always, masks. These masks become an extension of the characters who are revered and who are also counterparts of human ideals and vices. Different Ramlilas (Ram’s divine play), are usually based on the secondary text of Ramcharitmanas (an epic poem composed in the Awadhi language by Tulsidas in the 15th Century AD).

One of the oldest forms of Ramlila is performed in Ramnagar, in Varanasi, it is a two hundred years old tradition which was started by the king of Varanasi in the 17th century AD. It began with exemplary grandeur in the Ramnagar Fort by Kashi Naresh Balwant Narayan Singh and it was taken outside the fort premises by King Ishwari Prasad Narayan Singh (1857-1889) and introduced to the common folk of Kashi (present-day Varanasi). This 200-year-old play is performed traditionally without any lights or speakers, as the actors recited dialogues from different shlokas, decked with costumes and usually adorned with masks.

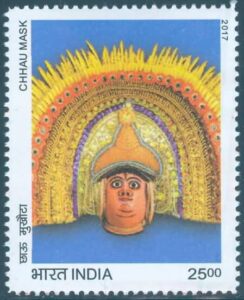

While Ramlila usually takes place in Delhi, Varanasi, Almora, and various local regions of Northern India, the eastern parts of India specifically West Bengal, Odisha and Jharkhand, have celebrated the decades-old tradition of Chhau dance enacts episodes from Ramayana, adding another layer of performativity to the text.

There are three iterations of Chhau – Seraikella(based in Jharkhand), Purulia (origins in West Bengal), and Mayurbhanj(performed in Odisha). The first two types include the usage of masks, made of clay which is layered over a wooden platform and kept in the sun to dry. Once it is dry, it is coated with a layer of paper, followed by a layer of cotton and then covered with a fine coating of clay. Once the layers have dried up the eyes and mouth are carved out and the masks are prepared for the dance. Chhau dance is a semi-classical dance with folk influences, and it is usually performed during spring, in Chaitra Parva, signifying the sun festival. Performed by males during the night time in spaces known as akhada or asar, Chhau is not a ritualistic practice, but rather a form of entertainment and community bonding activity. Masks play an important role in Chhau dance transporting the audience into a different realm altogether, they are ornate and meticulously designed, and even the skill of making the chhau masks is orally passed down from one generation to another.

The word chhau itself may have its roots in the Sanskrit word Chaya (shadow, image, mask) or chacma (disguise), meanwhile, Sitakant Mahapatra, Odia critic and poet, believes that the word is derived from chhauni (military camp, armour, and strength). This again showcases the intricate relationship between the dance and the usage of masks. The masks of Purulia Chhau are most decorative and elaborately designed, they are made in the village of Charida nestled under the Ayodhya hills in West Bengal, and a few hundred families of the village have been involved in the art of mask-making for generations. They were first made by Buddeshwar, whose contribution has been venerated by the villagers. The first chhau masks representing a man and a woman were known as kirat and kiratani, and that became the prototype for the chhau masks.

The masks used in the dance are huge and cover the whole face of the performer, transforming into a character from folklore. These masks are also made in smaller sizes as a collectable for people who want to use them as a decorative piece. The masks are also hung as part of outdoor displays for the mask shops and have become an integral part of the local landscape. Purulia Chhau masks are flamboyant and visually vibrant, and they follow a particular scheme for every character, representing different moods and temperaments. For example, the colour green is used to represent the character of Rama, and pink is used for Lakshamana’s masks. Seraikella chhau masks are similar to Purulia chhau, however, they are usually performed by the members of the Kshatriya caste, whilst Purulia chhau has members of scheduled castes. The tradition of Chhau dance and its elaborate costumes showcase a rich history of performance in the local culture of eastern India, celebrating the knowledge of Puranic epics through acts of creativity and innovation which also contributes to community building.

Whilst Chhau and Ramlila have more semi-classical backgrounds and are part of public formats of theatre and performance, Kathakali is a classical rendition of play and performance in Southern India, that presents Ramayana from a lens of elaborate gestures (Mudras) and movements.

Chronicling the lives of gods from mythological worlds through highly embellished masks, costumes, and vivid make-up. Kathakali is influenced by the old theatre tradition – Kuthiyattam, ritual performances and the regional material arts. Its theme for plays is based on Indian epics like Ramayana and Mahabharata.

Kottarkara Tampuran (Raja) in the second third quarter of the 17th century introduced a series of eight dance plays in Malayalam based on the Ramayana. Vettom Tampuran of North Kerala made changes in the presentation, make-up and costume of Ramanatham and Kotayam Tampuran (Raja) extended the style with writing. The dance stories that were based on the Mahabharata and gave a definite structure to stage performance. The style spread to other parts of Kerala and local troupes were set up in different places. Performances of Kathakali took place in open courts of temples, and it was a public affair; gradually it became popular all over the region

Kathakali originated in Kerala in the 17th century AD, and it is usually based on the narratives of Mahabharata, Ramayana and Puranas. With the patronage of the feudal chiefs from the kingdom of Tanur, the mask-making tradition and make-up changed in the Kathakali tradition, the blue used for divine characters was replaced with emerald green, which is the most distinguishable part of Kathakali. Masks for the animals and demons were replaced with facial paint, henceforth adding another layer to the meaning of the mask itself, as the transformation of a performer through costumes and adornment became more ingrained in the facial paints which acted as a form of an ‘ingrained mask’. At present there are four types of facial make-up styles: pacu (usually used to paint the divine or noble character), Katti or ‘knife’ type to delineate villainous characters, where the addition of an upturned red moustache outlined with rice paste is a signifier of evil and fiery viciousness, Kari used to paint the face of female demonesses, presenting her with a black face, and minshuku or radiant to illustrate noble or virtuous women like Sita, and even young Brahmin boys as well as sages, the colour used is a vibrant yellow-orange. Interestingly, in Kathakali masks are used to signify a transformation, for example, Bali’s son Angada wears a mask when he appears as a monkey on stage. The dance-drama elaborately presents various iconic moments from the text of Ramayana, transporting the audience to a different world of divine deities through elaborate costumes and make-up.

Ramayana theatre plays and masks in Southeast Asia

Ramayana has become a source of inspiration for different genres of performance art not just in India, but in various other Southeast Asian regions like Cambodia, Indonesia, Thailand, and Bali amongst many others.

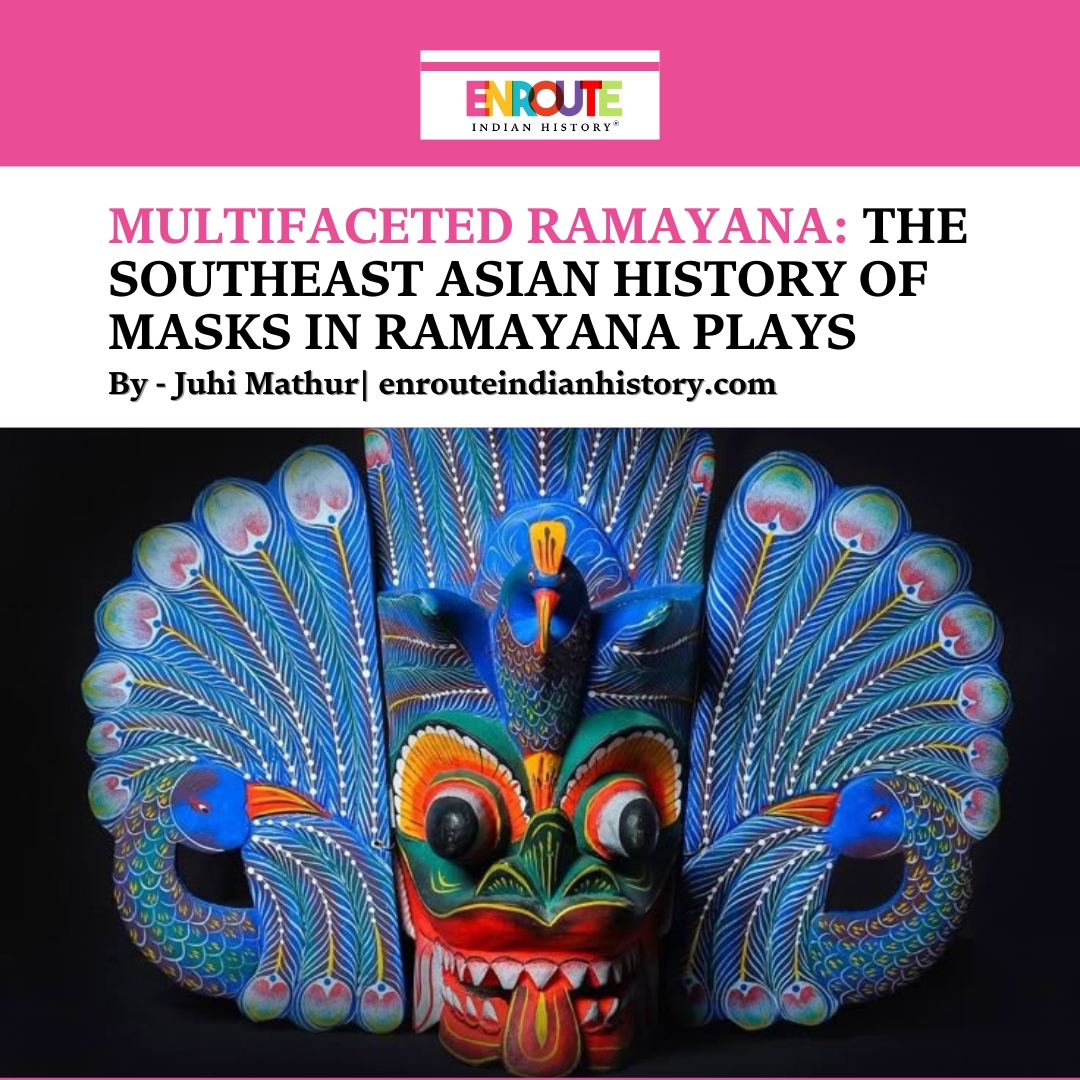

In Cambodia, the dance-drama genre of Lakhon khol is masked theatre dance which also has a performance based on Ramayana, it is known as Reamker and is based on the Khmer legend of Ramayana. Lakhon khol also known as lakhon khoal or lakhon bhoni has its roots in the Thai khon mask theatre, they both present the localised versionas of Ramayana, and in Thailand, it is known as Ramikien. Both are considered national epics and have paper mache masks for the animals and the demons, the main difference is that Lakhon Khol has masks for heroes and heroines and they are more robust, covering the whole head of the actors. The masks are embellished and gilded with extremely ornate headdresses. The earliest evidence of lakhon khol can be traced back to the 12th century CE, during the Angkor period under the reign of Jayavarman I.

The process of making lohon khol masks is tedious and it consists of many layers and stages of ornamentations as described by Cambodian artist Deth Sovutha, first a mould is prepared with soil for the main structure and then the head is made of paper or cardboard which is painted with various decorative patterns known kbach, the colours and designs of the mask represent the actual characters from the story, in Reamker (Cambodian iteration of Ramayana), Hanuman usually has a white face, while Ram has an emerald green mask, which is similar to the colour scheme of Kathakali. The masks are accompanied by a golden crown that adds to the vibrant opulence of this tradition of Khmer theatre.

Moving eastwards, in Bali there are two types of masked theatre traditions which present their versions of Ramayana: the wayang wong and the topeng, both of them derived from the traditions of Hindu court culture that was in itself inspired by Java and their present forms are derived from the Balinese courts in 17th and 18th centuries. The masks used in these plays are connected to certain artists and their families, and they are passed down from one generation to another as a family heirloom. Wayang wong (wayang: shadow, wong: man) was created in the 19th based on other forms of dance and performance – wayang kulit and gambuh, wayang wong came into existence as the king of Klungkung wanted the old, venerated and inherited masks used in a new form of theatre. Wayang Wong took inspiration from shadow play and dance styles from gambuh.

The masks used in Wayang Wong have Chinese influence and have elaborately ornate headdresses which at present are worn by the characters, specifically playing the demon and monkey characters, quite similar to the dance-drama theatre in Thailand. Monkeys are considered to be a symbol of divinity in Wayang wong and they are also considered guardian spirits, the mask representing Hanuman is usually painted in white colour. Most of the masks are accompanied by ear ornaments, headdresses, and even wigs, and all of these elements are considered to be holy objects which have a spiritual significance in Balinese performance arts, where the act of retelling the spiritual stories is an action of devotion itself.

All the actors perform various intricate movements and gestures, and the main characters deliver dialogues and sing songs in the Kawi language (old Javanese) while the supporting characters speak Bali. The Balinese wayang wong masks from the 16th century are kept in the Pemaksan temple in Buleleng regency, and the sacred wayang wong is performed on a particular day by the performers belonging to a certain lineage, carrying the traditions of their ancestors and serving the temple and its holy spirits.

Conclusion

Every aspect of these varied manifestations of theatre, dance, and performance shows the intricate relationship between the text of Ramayana and its versatile symbolism that has been celebrated and conserved through communal efforts. The performativity defines multifaceted and highly complex narratives of Ramayana and it also gives communities a goal to reiterate these epics and legends while keeping them alive and passing them down to younger generations, making the act of theatre a form of knowledge and also an act of remembrance. Through the study of masks and their inclusion in these traditions, we reach the oasis of contemplation where stories have inspired the creativity of human genius. In each of these dramatic renditions, masks reveal different facets of spirituality as well as provide us with meanings beyond the mere appearances, obscuring the performer behind it while granting him liberation to emote and transform into a new being again and again.

Bibliography

Blau, E. (1985, October 6). The epic Indian drama of Ramayana. *The New York Times*. Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/40460787

Cohen, M. I. (2019). Performing the Ramayana. Asian Theatre Journal, 36(2), 209-230. Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/27120405

Kumar, A. (2020, September 19). Ramayana and the footprints it left on the Southeast Asian region. Mashable Southeast Asia. Retrieved from https://sea.mashable.com/culture/12020/ramayana-and-the-footprints-it-left-on-the-southeast-asian-region

Kumar, B. (2023). A generalized view of the crafting and morphology of masks and masked performances in India. Indian Institute of Advanced Study. Retrieved from https://iias.ac.in/events/a-generalised-view-of-the-crafting-and-morphology-of-masks-and-masked-performances-in-india-excluding-the-bengal-region-an-insight-into-folk-culture/

Kumar, T. (2018, May 4). Ramayanas of South and South-East Asia. Frontline. Retrieved from https://frontline.thehindu.com/arts-and-culture/heritage/ramayanas-of-south-and-south-east-asia/article23595254.ece

Mitra, T. (2018). The Chhau dance in contemporary India. Asian Theatre Journal, 35 (1), 56-67. Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/26732449

Richmond, F. (1969). The Ramlila of Ramnagar. Educational Theatre Journal, 21(3), 245-255. Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/1124389

Telegraph India. (2022, October 5). A trip to Mukhosh Gram, Charida, the village of Bengal’s Chhau mask makers in Purulia. Retrieved from https://www.telegraphindia.com/my-kolkata/places/a-trip-to-mukhosh-gram-charida-the-village-of-bengal-chhau-mask-makers-in-purulia/cid/1890437

UNESCO. (2022). Chhau dance. Retrieved from https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/chhau-dance-00337

UNESCO. (2022). Lkhon Khol of Wat Svay Andet. Retrieved from https://ich.unesco.org/en/USL/lkhon-khol-wat-svay-andet-01374

UNESCO. (2022). Ramman: Religious festival and ritual theatre of the Garhwal Himalayas, India. Retrieved from https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/ramman-religious-festival-and-ritual-theatre-of-the-garhwal-himalayas-india-00281

UNESCO. (2022). Ramlila: The traditional performance of the Ramayana. Retrieved from https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/ramlila-the-traditional-performance-of-the-ramayana-00110

University of Massachusetts Amherst. (2022). Scenes from the Ramayana. Retrieved from https://fac.umass.edu/Online/default.asp?BOparam::WScontent::loadArticle::permalink=Scenesfrom&BOparam::WScontent::loadArticle::context_id=

Wayang Wong: The dance of the human puppets. (2020). NOW! Bali. Retrieved from https://www.nowbali.co.id/wayang-wong-the-dance-of-the-human-puppets/

Wikipedia. (2024). Chhau dance. Retrieved from https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chhau_dance

Wikipedia. (2024). Chhau mask. Retrieved from https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chhau_mask

Wikipedia. (2024). Lakhon Khol. Retrieved from https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lakhon_Khol

Dastkari Haat Samiti. (2020). The many faces of Purulia masks. Google Arts & Culture.. Retrieved from https://artsandculture.google.com/story/the-many-faces-of-purulia-masks-dastkari-haat-samiti/FgWxjtMD6J6BIQ?hl=en

Disco TEAK. (2020). Lakhon Khol. Retrieved from https://disco.teak.fi/Asia/lakhon-khol-2/

Kerala Tourism. (2021). Kathakali. Retrieved from https://www.keralatourism.org/kerala-article/2021/kathakali/1125

Map Academy. (2024). Kathakali masks. Map Academy Glossary. Retrieved from https://mapacademy.io/article/kathakali-masks/

Map Academy. (2024). Ramayana. Map Academy Glossary. Retrieved from https://mapacademy.io/glossary/ramayana/

The Better Cambodia. (2021). Discovering the Reamker: The epic story and cultural heritage of Cambodia. Retrieved from https://thebettercambodia.com/discovering-the-reamker-the-epic-story-and-cultural-heritage-of-cambodia/

Indian Culture: Government of India. (2021). Ramayana in Kodiyattam and Kathakali. Retrieved from https://indianculture.gov.in/intangible-cultural-heritage/performing-arts/ramayana-kodiyattam-and-kathakali