As the world grows into a place of budding economies constantly trying to modernize themselves, our war against nature and for nature has also intensified. In the past few decades, river disputes have increased enormously worldwide. When it comes to India, it goes from the Mahanadi water dispute to the Narmada water dispute, the tussle between states to share water basins has escalated. The oldest river disputes can be traced back to the Kaveri or Cauvery water dispute. Although many of us view it as a contemporary problem, it can be dated back centuries in its origins. As history holds witness, it only surged over time, even creating physical conflicts.

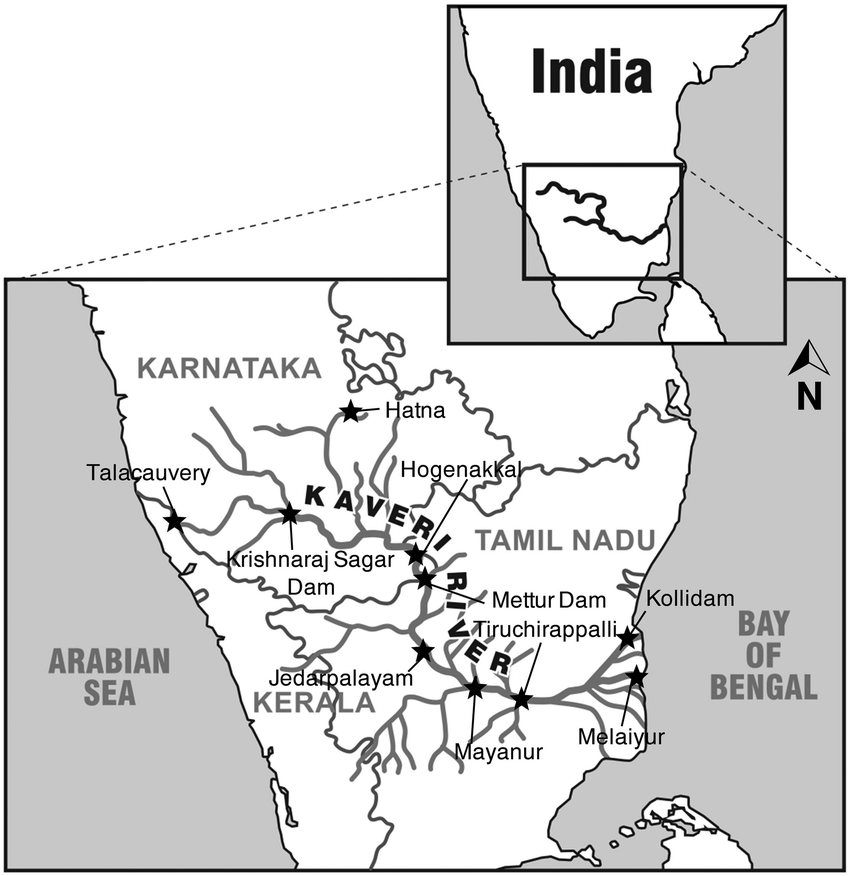

Map of the River Cauvery

The Battle of Centuries

The dispute is believed to have first appeared between the Hoysala and Chola kingdoms, who disagreed on how the water of the river basin would be utilized. One instance suggests that Chikkadeva Wodeyar attempted to build a barrier on the river to stop the flow into Madurai to seek revenge on the naik. Yet there isn’t surety on how the dispute unfolded in these centuries.

The modern beginning of the Cauvery dispute is dated back to 1807 between the then kingdom of Mysore and Madras presidency. It started when Mysore began the development of irrigation projects on the river, which threatened the water supply in Madras as mentioned in their memorandum filed under the Easementary rights of the state. These rights allow the land owner, in this case, the land of Madras being irrigated by Cauvery, to dictate the actions on the land. The memorandum filed by Madras was challenged by the tenth diwan of Mysore, Sir Seshadri Iyer creating a legal battle between the the two states.

The key to decoding this dispute lies in understanding the position of the two contenders. In the late 19th century, Madras was a British territory whereas Mysore was a princely state under Colonial rule. In the hierarchy, Madras held more power and could have easily undermined Mysore but the consultation of the ‘Indian’ government was taken to strike a balance. These negotiations led the representatives of both states to meet in 1890 to sort out their differences. The discussions formulated the general agreement of 1892 which stated that before Mysore could construct any irrigational project on the Cauvery river, permission had to be sought from Madras.

The conditions of the general agreement did not last long. In 1900, the kingdom of Mysore raised a proposal to build a hydroelectric station at Sivasamudra. This project was to play a key role in supplying water to the Kolar gold mines. Further, in 1910, plans for constructing the Kanambadi dam were proposed by Mysore deepening the conflict. Due to the worsening of the situation, the British government appointed Sir Henry Griffin to resolute the matter. Under him, a second agreement was signed on February 8, 1924, remaining valid for the next 50 years. According to this agreement, Madras approved the construction of the famous KRS dam on the river while it secured the right to build the Mettur dam in Tamilnadu. This agreement proved to be stronger than its predecessor, lasting its validity until disagreements restarted in 1974.

KRS Dam

Mettur Dam

The independence of India and the reorganization of states based on languages in 1956 created further complications in this river dispute. The origin of the river lies in Karnataka and some of its tributaries were now entirely flowing in the state of Kerala. Yet the issue remained heated mainly between the state governments of Karnataka and Tamilnadu. The government of Karnataka believed that the British government had favored the Madras presidency during the drawing up of previous agreements, which now seemed irrelevant. The disagreements often also translated into violence against the two communities living in the ‘opposite’ state. Negotiations were restarted and went on for almost 10 years but were futile.

As the states were not able to reach consent on their own, the government of India formulated the Cauvery water dispute tribunal on June 2, 1990, to decide the allocation of water among the states. The tribunal, after long discussions, provided an interim order on June 25, 1991, instructing Karnataka to release 205 TMC of water to the Mettur reservoir. Due to several deficits in the water release, the tribunal formed the Cauvery water authority in 1998 which was responsible for implementing the orders. Sadly, the formation of the tribunal did not end this river dispute, rather it was highly politicized.

Protests due to the Cauvery dispute

There were some years when Karnataka failed to release the ordered amount of water due to reasons like deficit rainfall and drought-like conditions like in 2016 when Tamilnadu moved to the supreme court. Tamilnadu was demanding the release of the deficit water as per the orders of the tribunal as the farmers of the state needed more water to grow samba, a specialty of the state. The legal battle concluded in the final verdict of the Supreme Court in 2018, where the volume of the water released to Tamilnadu was reduced to 177 from 192 TMC. The court also ordered the creation of a Cauvery management board, which would regulate the allocation of water based on the amount of rainfall and other condition of all four states. Presently, this board is responsible to regulate this dispute, and has been running smoothly on most occasions.

The verdict received a mixed reaction, with the state of Karnataka declaring it a victory whereas the state of Tamilnadu expressed their disappointment. These expressions are quite visible in the literature and films that have been created around the theme of the Cauvery dispute like the Tamil film Thambivudayan. There have been pieces portraying both sides but experts have also been questioning the ecological treatment of the river. In the chaos of this dispute, there wasn’t any focus on the condition of the Dakshina Ganga which plays an irreplaceable role in not only the agricultural development but also the flora and fauna. The water quality has severely degraded while there has also been a reduction in its volume.

Unfortunately, increasing river disputes have become our reality but looking at the Cauvery water dispute highlights that this is a problem that we have borrowed from the past. In a primarily agriculture country like India, the importance of controlling a river seems the only solution for the power holders. There is a constant fear of losing this means which translates into these disputes. It is time to look objectively at these issues and for the state governments to work cordially to use our natural resources in a sustainable matter because disputes like these leave an unerasable mark on generations to come.

References

-

- Rani, M. (2002). HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF THE CAUVERY WATER DISPUTE. Proceedings of India History Congress, 63, pp.1033–1042.

Pictures