Steady through the Storms: A Brief History of Indian Lighthouses Through the Ages

- enrouteI

- March 13, 2024

It is perhaps impossible to overstate how significantly the advent and spread of lighthouses revolutionised maritime trade. Used to ensure safety at sea, the bright beacons of lighthouses served several purposes—they would mark the beginning of land, indicate the entrance to ports and be used to warn ships and boats of potential dangers that could jeopardise a docking, like a rocky coastline. This article explores the remarkable history of lighthouses built in India, from the early constructions of a Deccan-based dynasty, to the spike in lighthouses throughout colonial history, and to the contemporary utility of these structures for surveillance, tourism and heritage.

Olakkaneswar Temple: The Flaming Eye on the Hill

Fire and light have a long history of being used to guide seafarers to safety. The foundational purpose of a lighthouse is to indicate where the sea ends and the shore starts, especially for vessels that travel in the dark of night. Before lighthouses existed, people would light blazing fires on beaches to mark the beginning of land. Later, these flames were moved to the tops of coastal hills, as the added height helped improve visibility. To aid ships travelling during the day, large piles of stones and rocks were used as markers instead. The lighthouse, as we know it, emerged from a blend of these two design elements of rock and fire (Goodall 2022), and an illustration of the same can be found very close to home.

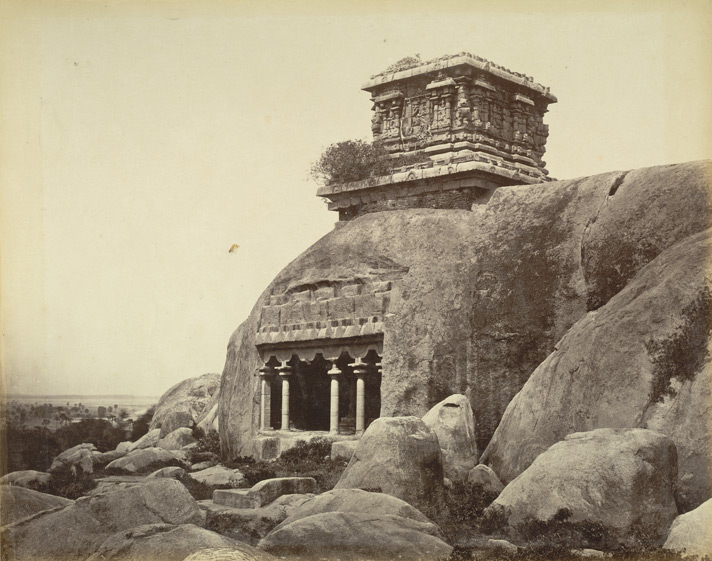

Amidst all the breathtaking rock-cut architecture found in the city of Mahabalipuram (around 60 kilometres from Chennai, Tamil Nadu), one structure stands out for the unique role it played in supporting ancient maritime trade. This is the Olakkaneswar Temple, constructed by the Pallava king Mahendravarman around 640 CE. While there is currently no idol in its sanctum sanctorum, the temple is thought to have been a refuge for worshippers of the god Shiva, especially since the Pallavas were enthusiastic supporters of Shaivism (Krishnamurthy 2017). What makes the Olakkaneswar Temple significant, however, is the purpose it may have served at night.

Research done by British archaeologist and art historian Albert Longhurst in the 1920s has recently been corroborated (Tripati 2009) to suggest that the Olakkaneswar Temple operated as an early lighthouse at night, making it the oldest documented lighthouse in all of Asia. At the top of the temple, archaeologists have found a small, shallow depression. Research suggests that this space held a pot that was filled with oil and ignited every evening “with the express purpose of orienting lost sailors and guiding them into safe harbour” (Kumar 2022). As the stone structure was on a hill and was the highest point near the shore, the added altitude allowed the fire to be visible to even the most distant of seafarers. This dual purpose renders the name of the temple even more significant—Olakkaneswar means ‘flame eye’ or ‘eye of fire’ and is a reference to Shiva’s all-seeing third eye. The flame on the top of the temple was eventually replaced by an electric light in 1887.

(a)

(b)

Figure (a): Olakkaneswar Temple, Mahabalipuram. Image by Nicholas and Company (1880). Source: Wikimedia

Figure (b): A close-up of a Chola-dynasty statue of Nataraja (11th Century CE), a dancing form of Shiva first popularised by the Pallavas. Note the faint impression of Shiva’s third eye.

Source: The Metropolitan Museum, New York.

Interestingly, the Olakkaneswar Temple is not the only lighthouse in Mahabalipuram. Towering right next to it is the modern Mahabalipuram Lighthouse, built by the British in 1904 and opened to the public in 2011 as a tourist attraction. A typical tourist day at the site would include a visit to both the old and new lighthouses, a joint example of the intermingling of pre-colonial history and European rule in the subcontinent. In fact, it was during the period of colonial history, especially under the British, Dutch and Portuguese, that the construction of lighthouses on the Indian coastline truly took off. In the next section, we focus on the role that lighthouses played in supporting imperial maritime trade, including an emphasis on the workers who operated the lighthouses and supported this all-important arm of the empire with their lonely, but invaluable labour.

The Lights and their Keepers: Lighthouses Under the Raj

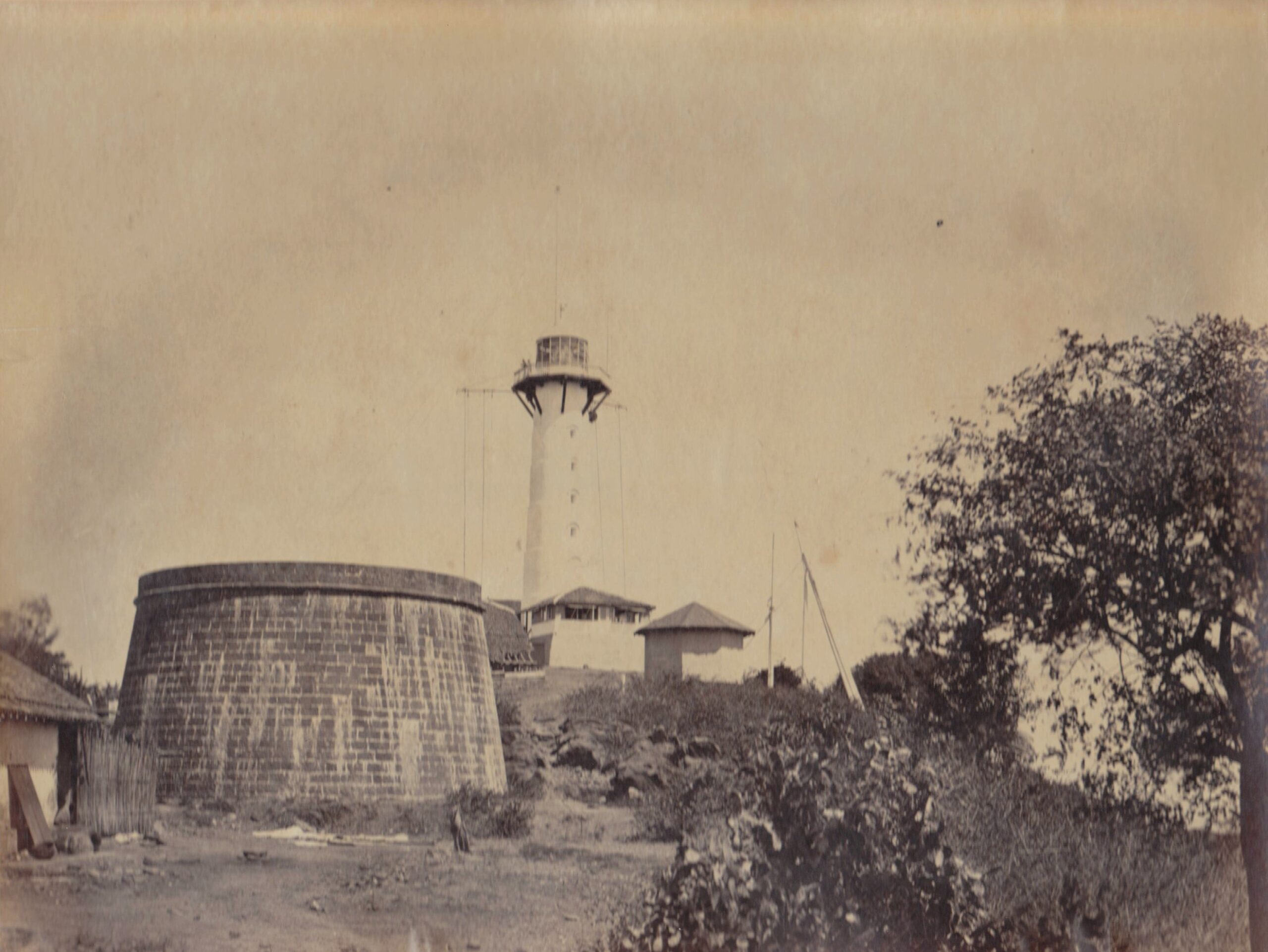

The spike in the construction of modern lighthouses emerged in the early 18th century, mirroring and aiding the emergence of large-scale, commercial transatlantic trade (Goodall 2022). When this trade expanded to include trade from the colonies, it became imperative to build lighthouses on colonial coastlines too. Many of India’s 203 lighthouses trace their origins to this period of colonial history. Thus, while India already boasts of the oldest instance of a pre-modern lighthouse in Asia, it was also the site for the construction of Asia’s first modern lighthouse—the Fort Aguada Lighthouse in Goa, erected in 1864. With advances in technology and architecture, lighthouses could now serve new purposes. Since the electric light within a lighthouse could be regulated, each lighthouse could flash its light in a unique pattern, offering sailors information about where they were located. Thus, in 1847, the lighthouse constructed on Colaba Point in Bombay had a revolving light that gave a bright flash every two minutes (Pandya 2023). Anyone who saw the light and timed the flashes would know precisely where, along the vast Indian coastline, they were docking.

(c)

(d)

Figure (c): Fort Aguada Lighthouse, Goa (2008). Source: Wikimedia Commons

Figure (d): The first lighthouse at Colaba Point, Bombay (1875), later demolished to construct the Prongs Lighthouse. Source: Michel, Flikr.

As tools of imperial maritime trade and colonial conquest, these lighthouses did more than merely guide ships and mark ports. For instance, the Fort Aguada lighthouse in Goa is part of a larger complex that includes barracks, bastions, a gunpowder room and even a modified prison. In this manner, one could argue that the lighthouse became a symbol of colonial might. Every new lighthouse was not only an asset for the outrageously exploitative colonial trade, but also a means of controlling and disciplining the native coastline. It was because of the rapid construction of new lighthouses, and the need to govern and manage the ones that already existed, that the British Raj constituted a Lighthouse Department in British India and introduced a bill that became the Lighthouse Act of 1927.

Today, a vast majority of lighthouses in India are fully automated. However, in much of the fiction and history surrounding colonial lighthouses, the role and struggle of the lighthouse keeper is central. According to Goodall (2022), lighthouse keepers were the pulse that kept these structures running—they were responsible for maintaining the buildings, operating the lamps, trimming wicks, replenishing fuel, and winding the clockworks. Keepers would usually stay on the premises, often with their families. Theirs was a tiring and isolating job, often living for years on the outskirts of settlements without amenities like running water or heating systems.

In his splendid article for The Financial World, Dominick Rodrigues (2023), shares the stories of Joan Costa, an Anglo-Indian whose family were lighthouse keepers for two generations. Her Portuguese paternal grandfather, William Noronha, retired as the keeper of Thangassery Lighthouse, in Kollam City, Kerala. Costa’s father, Bertram Noronha, took up a job as an assistant lighthouse keeper at Vengurla Lighthouse in Maharashtra. As Goodall (2022) details, lighthouse keepers are often shifted from one posting to the next, which was true of Bertram’s journey as well. Vengurla was only the first stop in a career that included postings at the lighthouses of Oyster Rock and Bhatkal in Karnataka, along with Jaighar, Uttan and Tarapur lighthouses in Maharashtra (Rodrigues 2023).

“The lighthouse keeper’s job was to flash the lighthouse light from 6 p.m. to 6 a.m. daily for warning shipping and helping them to identify and avoid the rocky areas on their journey. Contact to the mainland was through a signalling lamp, besides a Grundig radio for music and news,” Joan recounts in her interview (Rodrigues 2023). She also mentions how some of her father’s postings were on islands without medical facilities and shares stories of how family members would have to row back and forth from the mainland to source daily amenities.

While modern automation of lighthouses has relieved people of this isolating, taxing job, it is crucial to preserve the histories of keepers as a part of the colonial history of Indian lighthouses. Without their sacrifices and labour, the colonial empire would have lost control of the lighthouses and, consequently, compromised much of their maritime trade, sea travel, and military might.

Security, Surveillance and Celebration: Modern Lighthouses in India

The rather common assumption that lighthouses are outdated, vestigial remnants of a nostalgic past can be dispelled with a quick overview of the many purposes that the structures continue to serve today. In modern times, lighthouses continue to guide ships, mark ports and send signals. While technology like GPS tracking makes it easier for vessels to navigate the seas, lighthouses are still valuable backup options, especially in the case of adverse weather or technology failures. Lighthouses have been used for weather forecasting, and in some parts of Europe, they have been converted into luxury hotels or wedding venues.

In India, lighthouses became especially important after the 2008 26/11 terror attacks in Mumbai. As a response to the attacks, some lighthouses have been equipped with state-of-the-art radars to keep an eye out for any suspicious movement along India’s 7,500-kilometre-long coastline (Menon 2016). In 2012, the Indian government spent over 130 crores to establish the Automatic Identification System (AIS) network, with technological support from Swedish partners. The AIS allowed small boats and independent fishermen to communicate with 74 selected lighthouses, thereby “providing real-time merchant traffic information” (Jenkins and Koshy 2012).

(e)

(f)

Figure (e): Corsewall Lighthouse in Scotland, which has been renovated into a luxury hotel. Image by John Harris (2020). Source: Corsewall Lighthouse Hotel Website.

Figure (f): Decorations were projected onto the lighthouse at Fort Aguada for the 2023 Indian Lighthouse Festival. Source: Press Information Bureau, Government of India.

More recently, efforts have been made to tap into lighthouses as tourist and heritage hotspots. Thus, in 2021, the BJP government introduced the Marine Aids to Navigation Act, which replaced the colonial Lighthouse Act of 1927 and offered new avenues for developing the historical, educational and cultural value of lighthouses. In September last year, Fort Aguada in Goa saw the launch of a three-day ‘Indian Lighthouse Festival’ (PTI 2023), which focused on using public-private partnerships to rekindle interest in 75 Indian lighthouses that have rich histories and heritages. The festival saw cultural exhibitions, sessions highlighting maritime trade history and culture, classical performances, light and sound shows, performances by celebrity singers, coastal cuisine and community engagements (Rodrigues 2023), all dedicated to the cause of generating greater interest in India’s iconic lighthouse legacy.

Perhaps the next time you find yourself somewhere near the coast, you’ll peruse some of that legacy yourself! Visit a local lighthouse to catch a glimpse of their centuries-long role in trade, conquest and travel—or simply grab the chance to soak in a seaside sunset from a truly unparalleled vantage point.

References:

Goodall, R. (2022). Time Travel – The History of Lighthouses. The Boar. https://theboar.org/2022/12/time-travel-the-history-of-lighthouses/

Jenkins, C. and Koshy, J.P. (2012). Saving the Lighthouse. The Mint. https://www.livemint.com/Politics/vym079fWQoaJECY5TXwBMN/Saving-the-lighthouse.html.

Krishnamurthy, S. (2017). Pallava Period: Social and Cultural History. Wisdom Library (Open Access). https://www.wisdomlib.org/history/essay/pallava-period-study

Kumar, S. (2022). Is This 7th-Century Temple India’s Oldest Lighthouse? Condé Nast Traveller India. https://www.cntraveller.in/story/is-this-7th-century-temple-indias-oldest-lighthouse/.

Menon, R. (2016). Keepers of the Light. The Indian Quarterly. https://indianquarterly.com/?p=1993.

Pandya, M. (2023). Lighthouses: Beacons of the Coastline. Millennial Matriarchs. https://millennialmatriarchs.com/2023/09/28/lighthouses-beacons-of-the-coastline/.

PTI (2023). India’s First Lighthouse Festival Opens in Goa; Spotlight on 75 Historical Sites to Be Developed as Major Tourist Spots. Deccan Herald. https://www.deccanherald.com/india/goa/indias-first-lighthouse-festival-opens-in-goa-spotlight-on-75-historical-sites-to-be-developed-as-major-tourist-destinations-2698562.

Rodrigues, D. (2023). Indian Lighthouses Festival in Goa Highlights Maritime Tourism. The Financial World. https://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.thefinancialworld.com/indian-lighthouses-festival-in-goa-highlights-maritime-tourism/&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1709894268631478&usg=AOvVaw18Ype19pbxLhBzEjG9AajY.

Tripati, S. (2009). Coastal Structural Remains on the East Coast of India: Evidence of Maritime Activities and Their Significances. In: P.C. Reddy, ed., Saundaryashri: Studies of Indian History, Archaeology, Literature & Philosophy. New Delhi: Sharada Publishing House, pp.695–703.

- May 15, 2024

- 6 Min Read