By Tabia Masoodi

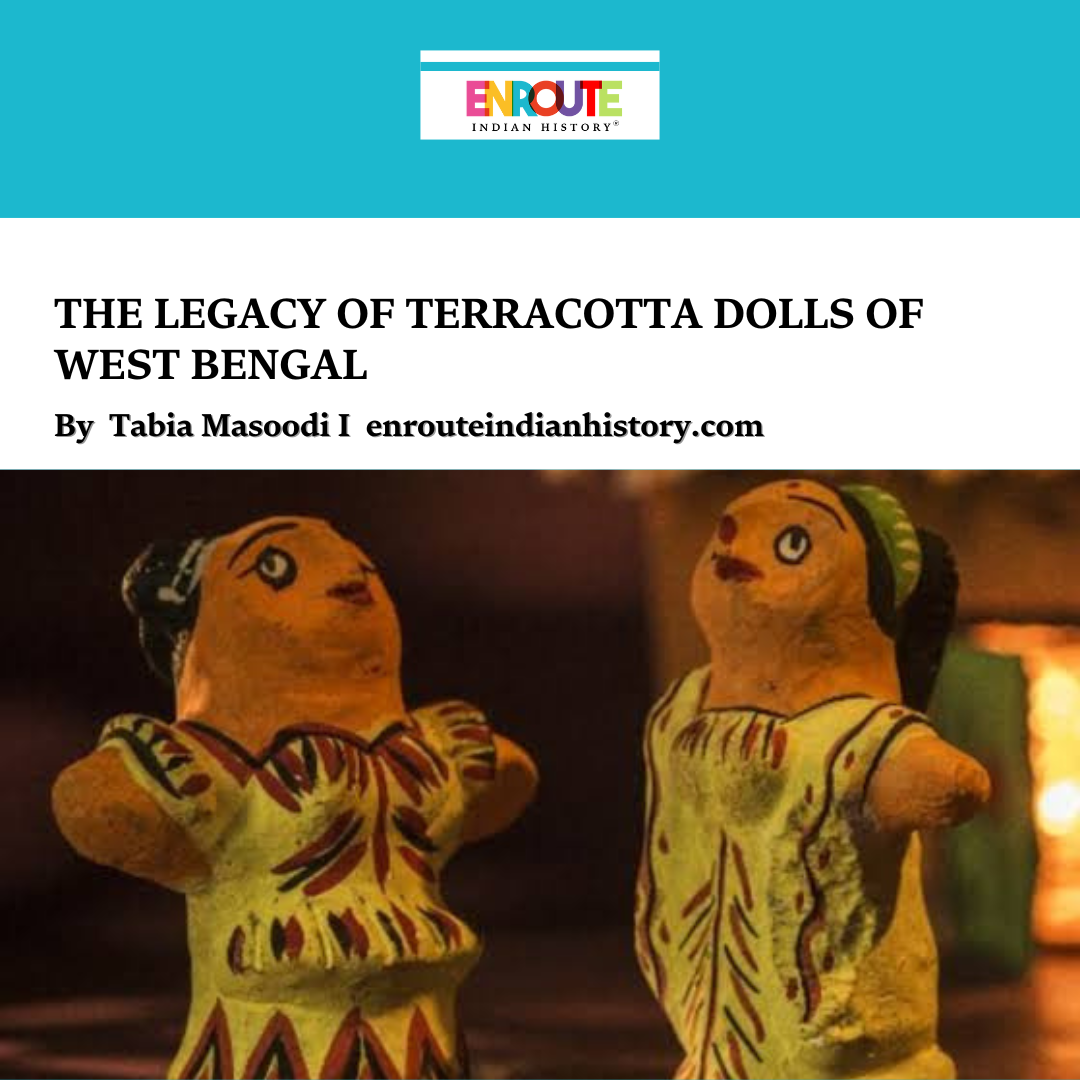

In the villages of Bengal, the earth reveals its art to the very life it sustains. It guides them to immortalise their stories, heritage, and culture with its soil. Emerging from the soil, the art is moulded by hands deeply rooted in tradition, the timeless art form is called Terracotta art. Terracotta is an Italian word that translates to baked earth. Terracotta originates from the Latin terra cocta meaning cooked earth. The masterpieces created with clay are much more than simple artefacts as they reveal the reflections of past cultures. West Bengal boasts a rich tradition of cultural and historical terracotta artistry that dates back to ancient times. Archaeological excavations at sites like Chandraketugarh, Tamluk, and Harinarayanpur have uncovered ancient terracotta figurines, showcasing Bengal's enduring legacy of clay artistry. Terracotta art enhances nearly every aspect of Bengal's culture, as seen in terracotta temples, figures, decorative panels, terracotta horses, and terracotta dolls, which tell the stories of the region's heritage. Among all Bengal’s art forms, Bengal has a long-standing history of doll making that is not merely decorative but is deeply rooted in folklore and holds religious and ritualistic significance.

HISTORICITY OF TERRACOTTA DOLLS

Terracotta art has always played an important role due to Bengal's scarcity of stone resources. Terracotta dolls of Bengal are traced back to the pre-Mauryan era before 322 BCE, who used them for religious purposes such as the matrika(mother-goddess) found in archaeological sites like Pandu Rajar Dhibi and Harinarayanpur. These figurines represented fertility and strength as well as were integral to the agrarian community. The technique was not sophisticated as artisans focused more on functionality than design. However, the era established the artistic framework, influencing the motifs seen during the later periods.

This art flourished during the Mauryan period (324-187 BCE) and was characterised by exceptional artistry. Dolls from this era had exquisite features such as facial expressions, hairstyles, and jewellery, demonstrating their ritualistic importance. Muaryan terracotta dolls were more refined with expressive details. The Mauryan period established a standard for early Indian terracotta craft by fusing artistic inventiveness with the technical innovation of mixed moulding.

Archaeological evidence from the Kushan era(1st—3rd century CE) is found at sites like Chandraketugarh and Tamluk. In Chandraketugarh, a prominent example that reflects motifs from local lore shows a male figure sitting on top of a tiger in a temple-like structure. These dolls display elaborate detailing and moulding techniques, with incised lines and surface stippling emphasising anatomical aspects. Artefacts from the Kushana period demonstrate sophisticated craftsmanship through the use of single moulds and fine clay fabric. During the Gupta period (4th- 6th century CE), terracotta artistry thrived as an essential art form representing the cultural splendour of the time. Plaques and figurines portraying gods, scenes from mythology, and daily life were crafted and employed to decorate temples and sacred places. The experienced terracotta artisans emitted complex replicas that fall into two primary groups: human and divine figures. The potter’s proficiency was demonstrated by the technical skill needed to bake these enormous masterpieces. The art kept flourishing under different patronages. During the Pala dynasty(8th – 12th century), the art blended Hindu and Buddhist motifs and prospered significantly depicting mythological tales and folk traditions.

ORIGIN IN FOLK RITUALS, RELIGIOUS TRADITIONS AND CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE

Terracotta dolls have served as symbolic objects, embodying spiritual beliefs, cultural narratives, and artistic traditions. As clay is considered sacred in Bengali culture, terracotta is an ideal medium for ceremonial practices. The clay dolls have been an integral part of both religious rituals and folk practices. They were used as votive offerings to deities, representing gratitude. For example, clay horses and elephants were devoted to village guardian deities in Bengal, illustrating a combination of animistic beliefs and Hindu traditions. These dolls carried symbolic meaning, for instance, the hairpins on female figurines and figures such as Shashti Putul symbolized fertility and were used in rituals seeking blessings in childbirth.

The male figurine seated on a tiger found in Chandraketugarh symbolizes divine power and protection. Bengal terracotta dolls are strongly ingrained in local culture and celebrations. During Durga Puja, craftsmen create small clay goddesses like Lakshmi and Durga, showing the merging of art and devotion. Rural fairs, such as those in Bankura and Krishnanagar, display these dolls as emblems of heritage, serving both ritualistic and cultural storytelling purposes. The terracotta dolls mimic the daily lives and ambitions of rural communities. The terracotta figurines are also an active agent in highlighting cultural elements of Bengal depicting rural landscapes and mythological episodes serving as a medium for storytelling and persevering

the folklore and oral traditions of Bengal. The Krishnanaagr’s terracotta dolls depict farmers, festivals and the overall socio-cultural fabric of Bengal( (Hazra and Barman, 2017). Each region has a distinct style that celebrates and glorifies West Bengal culture.

MAJOR REGIONAL VARIATIONS AND STYLES

Terracotta dolls of West Bengal vary widely across different regions. Each region has its unique techniques and themes. These variations are a witness to Bengal’s enduring legacy.

Bishnupur Heemputul:

The dolls are predominantly crafted by the women of the Foujdar family of Bishnupur using centuries-old techniques, these finger-sized figurines are traditionally fashioned using local clay, sun-dried, and dyed with natural pigments like cinnabar (hingul), a mercury sulfide mineral mined in Bankura and Purulia. The dolls are called Heemputul derived from hingul. While modern versions employ herbal dyes, the historical use of hingul remains central to their identity, lending the dolls their signature red hue. The Heemputul is originally rooted in ritual use as a votive offering as Shoshthi dolls in Shoshthi Puja, done for fertility. The Shashthi dolls are seen as maternal figures carrying children. However, it bifurcates into ritualistic and secular categories, with the non-ritual variant serving as children’s toys.

The dolls present a fusion of colonial and indigenous influences: their apparel frequently consists of Western-style garments, caps, and dresses, which are a remnant from past encounters with European aesthetics through tepa putul (dolls formed by fingertip pressing).

Lac-Coated Terracotta Dolls:

A folk art form of West Bengal, lac-coated clay dolls are widely found in Purulia, Birbhum, Bankura, and Medinipur. These dolls are crafted by conch shell artisans called Sankhakars using termite hill clay and a natural lac resin. The clay is steeped for two to three days, kneaded until smooth, and then sculpted into figures with fingers( (Singh, 2021). The dolls are covered in lac, a natural resin made from insects on Kusum trees, after being dried and baked in home ovens. The lac is heated with colours to form colourful sticks, which are then melted and put on the dolls' surfaces. This method produces vivid front-facing colours such as red, yellow, and green, while the backs are often coated in black. The dolls feature intricate detailing which is achieved by using thin threads of lac, known as Guna work, which are pulled from softened lac sticks to form features like hair, eyebrows, and jewellery. The lac-coated terracotta dolls in Bengal are commonly referred to as Shashti Putul as these represent the themes of fertility and mother-child figurines. Apart from these, figures of Hindu deities and animal symbolism as well as depiction of rural life are also common

themes.

Krishnanagar Ghurni Dolls:

Having a legacy that spans over 200-250 years, the Ghurni dolls of Krishnanagar crafted by the Pal community are an enduring example of miniature realism. The art thrived under the patronage of Maharaja Krishnachandra (1710-1783), who brought potters from Dhaka and Natore (modern-day Bangladesh) to reside in Ghurni (Chaudhary, 2023). The dolls are typically 2-6 inches tall and are known for their emotive detailing. These dolls are made using sophisticated techniques. Artisans sculpt the clay using delicate tools and iron rods for skeletal support. After baking in kilns, the figurines are painted with vivid colours and lacquered to ensure longevity. Some are attired in beautiful clothes to enhance their realism. The dolls show the daily life and emotions of the people of West Bengal and narrate stories of folklore and social themes. It includes farmers ploughing fields, weavers at work, basket makers crafting bamboo wares, Santhal tribal dancers, priests performing rituals, beautifully adorned brides and grooms, colonial caricatures and nature.

Mojilapur Dolls:

Sambhu Nath Das, the eighth-generation craftsman and grandson of Manmatha Das, who earned the President's Award in 1986 for his legendary Jagannath-Balaram-Subhadra trio, solely continues the 250-year-old heritage of Mojilpur doll making. The dolls are crafted in Joynagar-Majilpur in West Bengal. The dolls are created from the soil obtained from termite hills or local fields. A two-part mould is used to craft the dolls which create a hollow figure that is joined to form a lightweight structure. The dolls are then fired except the figurines of deities, painted and coated with garjan(balsam) oil to add lustre and increase the durability of the dolls. The common themes include religious and folk deities like Durga, Kali and Bonbibi – the folk goddess of Sunderban forests. The themes also include the caricatures of colonial satire of Bengali elites and Britishers such as Babu Putul and Ahlad-Ahladi.

Bengal’s terracotta dolls are a witness to its daily life, heritage, and culture as well as central to its folk traditions and religious practice. It is not just a creative expression but a window to living as well as the dead of Bengal, connecting Bengal's ancient past with modern cultural identity. However, the low income of artisans, lack of government support and a dearth of scholarship have led to the decline of this ancient art form.

References

Thakur, Meenakshi. “Ancient Terracotta art of Bengal – a living tradition.” Shikshan Sanshodhan: Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, vol. 5, no. 4, 2022, p. 4. shikshansanshodhan.researchculturesociety.org,

https://shikshansanshodhan.researchculturesociety.org/wp-content/uploads/SS202204002.pdf.

Sarkar, Sibnath. “Terracotta – the Indigenous Craft of Bengal: A Case Study of Panchmura, Bankura, West Bengal, India.” Academia.edu, 2023,

https://www.academia.edu/120557340/Terracotta_the_Indigenous_Craft_of_Bengal_A_Case_Study_of_Panchmura_Bankura_West_Bengal_India. Accessed 11 April 2025.

MAP Academy. “Chandraketugarh Terracotta Objects.” MAP Academy, 27 September 2023, https://mapacademy.io/article/chandraketugarh-terracotta-objects/. Accessed 11 April 2025.

Hazra, Kandarpa Kanti, and Arup Barman. “PROSPECT OF TRADITIONAL CRAFT IN PRESENT ECONOMY: A STUDY OF EARTHEN DOLL OF

KRISHNAGAR, WEST BENGAL.” IAEME Publication, vol. 8, no. 4, 2017, p. 75. academia.edu,

https://www.academia.edu/35654533/PROSPECT_OF_TRADITIONAL_CRAFT_IN_PRESENT_ECONOMY_A_STUDY_OF_EARTHEN_DOLL_OF_KRISHNAGAR_WEST_BENGAL.

AsiaInch. “https://asiainch.org/craft/lac-terracotta-dolls-of-west-bengal/.” asiainch.org, NA, https://asiainch.org/craft/lac-terracotta-dolls-of-west-bengal/. Accessed 12 April 2025.

Biswa Bangla, An initiative of the Department of MSME & Textiles, Government of West Bengal. “DOLLS OF BENGAL.” monidipa.net, 2015, https://monidipa.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/7dd31-dollsofbengal.pdf. Accessed 11 April 2025.

Singh, Gurvinder. “Bengal’s traditional shellac dolls face lacklustre future.” Village Square, 10 March 2021, https://www.villagesquare.in/bengals-traditional-shellac-dolls-face-lacklustre-future/.

Chaudhary, Sahmita. “TERRACOTTA ART AND CRAFT OF BENGAL: A LIVING TRADITION OF INDIA.” A Global Journal of Humanities, vol. 7, no. NA, 2023, p. 6. gapbodhitaru.org, Available at: Researchgate/terracotta art and craft of Bengal

GetBengal. “Visit Bishnupur not just for its temples, but for the Heemputul.” Get Bengal, 21 January 2021, https://www.getbengal.com/details/visit-bishnupur-not-just-for-its-temples-but-for-the-heemputul. Accessed 11 April 2025.