Article Written By EIH Researcher And Writer

Barnak Das

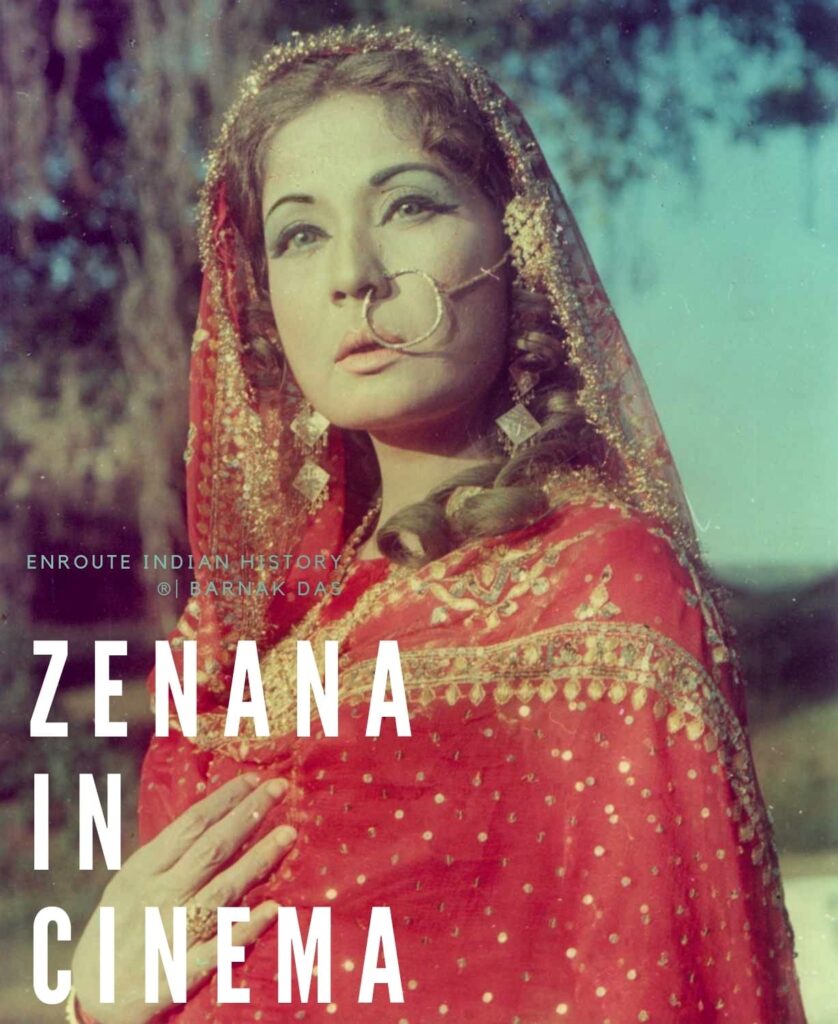

The zenana was a women’s court or female quarters of palaces or royal households in the Indian subcontinent. The zenana was a Persian institution that came into the Indian subcontinent with the arrival of Islamic rulers. It was later adopted by Hindus, especially Rajputs alongside the practice of Purdah. The tradition of the zenana continued in India over several centuries. Following India’s independence in 1947, the Indian princely states were amalgamated into the newly formed Indian republic. With it, zenana, or the practice of the princely households to maintain separate, segregated spaces for women also ceased to be practiced.

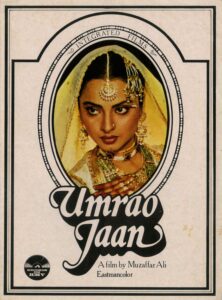

Even though the princely states and their court culture lapsed with the birth of the Indian republic, the aesthetics of courtly opulence, pageantry and visual splendour in ornate garments, glittering jewellery and palatial settings dominated Indian cinema for a long time. The courtly aesthetics of the zenana were re-imagined through films such as Raj Nartaki (1941), Mughal-e-Azam (1960), Pakeezah (1972), Umrao Jaan (1981), Ekalavya (2007) and Jodhaa Akbar (2008). These films depicted the zenana women in two ways: as tawa’if (courtesans) and royal wives. They became the exclusive windows into the interior of the pardah compartments previously inaccessible to people other than royal women. They uncovered the mystery of women living inside the zenana through incorporating them as characters in the plot of the cinema’s story. The pardahnashinwomen, previously secluded from the outside world, were unveiled and their person – both corporeally and spiritually was made visible to the audience.

Be it Mughal-e-Azam (dir. K Asif, 1960), which romantically depicted the love story between Prince Salim and the dancing girl Anarkali in 16th century Lahore; Pakeezah (dir. Kamal Arohi, 1972), which narrates the story of a Muslim courtesan; or Umrao Jaan (dir. Muzaffar Ali, 1981), which tells the trials of Muslim tawa’if in twentieth century Lucknow; all had a central space and explored the visual setting of the courtly zenana. Many films such as Asoka (dir, Santosh Sivan, 2001), Ekalavya (dir, Vidhu Vinod Chopra, 2007) and Jodhaa Akbar (dir. AsutoshGowarikar, 2008), were shot in erstwhile zenanas of princely palaces to give a feel of authenticity to the audience.

The Bollywood industry cleverly used the fascination of the Indian audience to courtly aesthetics of a by-gone age. Directors of early Bombay film industry utilised the music, dance and dress of zenana courts and sometimes even the displaced tawa’ifs from royal households (after the lapse of the Privy Purse under Indira Gandhi) in their films. With them also came the stories of the tawa’ifs into the big screen of cinema. Many of such stories were used as plots to popular commercial films. The Malabar Hill Murder, which came to the Bombay court in 1925, was one of them. It involved a Muslim tawa’if and her princely lover, the Maharaja Tukoji Rao Holkar of Indore. The girl, named Mumtaz, survived an abduction attempt to give oral evidence which eventually led the Maharaja to abdicate in 1926. Her tale was taken by Bollywood and made into the film Kulinkanta (dir. Homi Master, 1925).

There is no doubt that the zenanas were hierarchical and polygamous institutions, but they served to bring together women of different caste, religious, linguistic and clan affiliations and created a heterogenous, cosmopolitan microcosm in a male dominated society. Originating from the zenana, the tawa’if or courtesan films became so popular that it developed its own sub-genre in Hindi-Urdu cinema. The film historian Rachel Dwyer believes that using the tawa’if as a subject in film enabled the viewer (predominantly common people) to enjoy the ‘spectacle of the body, the elaboration of scenery and in particular of clothing.’ The sensual environment of the royal zenana with Persian carpets, crystal candelabra, courtyards, fountains, and elaborate clothes overwhelmed the viewer.

The zenana was used as a popular device used in the fantastical construct of a princely India; it was used from early Bollywood films of Bombay to give a glimpse of royal courtly life to the general audience of India. With its popularity, the films continued to explore more themes and characters in the backdrop of the zenana. This in turn led to the popularising of royal aesthetics in a sense of glorified nationalism. Over the years, the music and dance of courtesans along with vibrant jewellery and elaborate dresses found its way into what we today identify with typical Bollywood cinema. Through its visual representation of royal splendour and glorified culture, the courtly zenana still fascinates the imagination of an Indian viewer.

References

Rachel Dwyer, ‘Representing the Muslim: The “courtesan film” in Indian PopularCinema,’ in Tudor Parfitt and Yulia Egorova eds Jews, Muslims, and Mass Media:Mediating the ‘other,’ p. 88. Routledge, 2004.

Jhala, Angma Dey. “From zenana to cinema: The impact of royal aesthetics on Bollywood film.” In Popular Culture in a Globalised India, pp. 159-174. Routledge, 2009.

Jhala, Angma Dey. “Shifting the gaze: Colonial and postcolonial portraits of the zenana in Hindi and Euro-American cinema.” South Asian Popular Culture 9, no. 3 (2011): 259-271.