During an era when the quest for discovery and exploration was at its peak, India held a special place in the hearts of adventurers from distant lands. India has long been a captivating enigma, enticing travellers with its vibrant culture and exotic allure. These intrepid voyagers brought unique perspectives, shedding light on the intricacies of Mughal India’s way of life. While the Mughal dynasty’s accounts provide invaluable insights into the realm and the court, it is the narratives of these travellers that offer a sharper, more vivid portrait of the time. Yet, while these explorers from distant lands brought fresh perspectives, it is essential to acknowledge that their accounts were not always entirely accurate or precise. Often reliant on bazaar gossip and secondhand information, these travellers shaped their narratives through the lens of their personal opinions as well.

Among the many captivating facets that left the foreign travellers astounded, none rivalled the mystique and intrigue of the Mughal Harem. The Mughal Harem stood as an unparalleled source of fascination for foreign travellers, leaving them awestruck with its mystique. What captivated them most was the inherent intrigue surrounding this secluded world, as they were denied direct access or contact with its inner workings. It was customary for travellers to take a keen interest in describing the women of the lands they visited, and European explorers of the seventeenth century were no exception. The Harem, in particular, was regarded by foreigners as a realm of exotic curiosity, both fascinating and unsettling. However, when it came to depicting the Mughal Harem, European travellers faced two significant challenges. Firstly, being foreigners, they possessed limited resources to fully comprehend the language and culture of the locals. Secondly, as men, they were inherently barred from entering the private domain of women, rendering it nearly completely inaccessible to them.

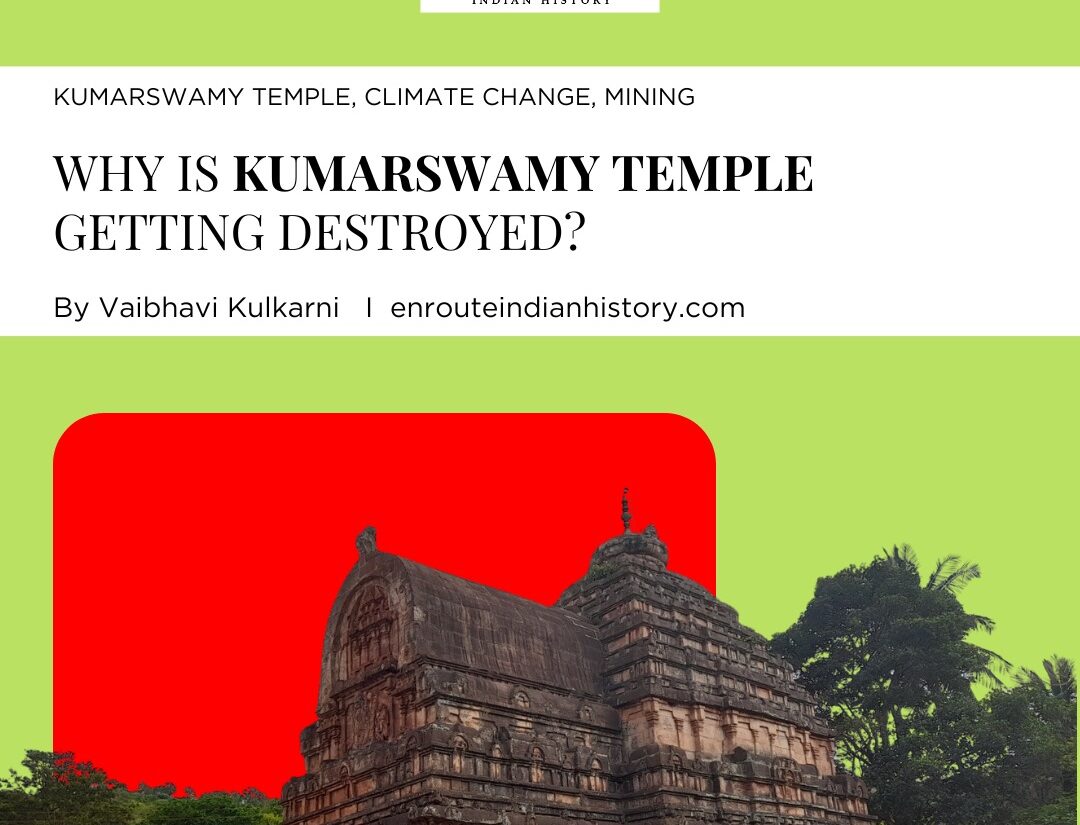

A young woman on a canopied bed outdoors on a stormy night, has her feet massaged. Image Source : San Diego Museum

The term Harem originated from the Arabic word “haram,” which initially referred to a sanctuary and carried connotations of sacredness. Additionally, it was known by various names such as zenanah, harem-sara, harem-gah, mahal-sara, and raniwas. Abul Fazl, in his work Ain-i-Akbari, used the term Shabistan-e-iqbal, meaning the “harem of fortune,” to describe the Mughal Harem. European travellers typically favoured the term “harem” but also employed “mahal.” However, their usage of these terms differed significantly. They interpreted these terms to encompass a system allowing males’ sexual access to multiple females, often leading to Western men expressing moral condemnation due to the perceived promotion of sexual laxity and immorality within the system. William Finch’s description of the very location of the mahal revealed its centrality to the Emperor: “Within the second court is the mahal, . . between each corner and this middle, most are two fair large chambers for his women (so that each mahal receives sixteen) in separate lodgings, without doors to any of them, all keeping open house to the King’s pleasure. . . . amid all the court stands the King’s Chamber, where he, like a cock of the game, may crow overall.”

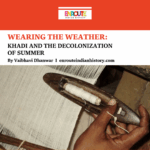

‘Ladies of the zenana on a roof terrace” by Ruknuddin. Bikaner, 1675. The Kronos Collections

The harem complex, shielded by imposing walls to uphold the tradition of purdah, housed a collection of exquisite buildings. Its layout featured a sequence of annexes carefully crafted to provide an atmosphere of spaciousness and comfort, complete with a central courtyard where joint celebrations took place. The complex boasted enchanting elements such as fountains, ponds, gardens, and orchards, intended to offer a sanctuary for the women who often spent their entire lives within its confines. The apartments were intricately interconnected, forming a labyrinth of interconnected spaces. Access to the harem was limited to a single entrance door, vigilantly guarded and strictly controlled.

Two ladies sharing a tender moment. Attributed to Govardhan, Mughal, circa 1615-20.

Opinions and Imaginations

The imaginations of these travellers ran wild as they speculated about the vast number of women residing within the King’s palace, resulting in varying figures being provided. Niccolo Manucci, an Italian adventurer, claimed that “ordinarily there are within the mahal two thousand women of different races.” Another English explorer, Thomas Coryat, affirmed that Emperor Jahangir “keeps a thousand women for his own body.” Francisco Pelsaert, a Dutch traveller, marvelled at how the governors would fill and adorn their mahals with beautiful women, transforming them into pleasure houses that seemed to encompass the entire world within their walls. The reality differed significantly. Only a small percentage, around five per cent, consisted of queens, concubines, and slave girls of the king. The majority of the harem residents included mothers, stepmothers, foster mothers, aunts, grandmothers, sisters, daughters, and other female relatives of the king. Male children also resided within the harem until they grew up. Eunuch guards protected the harem, while female fortune tellers and entertainers added to its vibrant community.

Another fascinating observation made by the Travellers was about the entrance of physicians into the harem, highlighting its unique protocols. Among the adult males, only the emperor had unrestricted access to the harem, while royal princes who reached puberty were prohibited from entering. However, physicians were an exception, although their entry was subject to strict veiling and covering. Hakeems and later European physicians, such as Italian adventurer Francesco Carreri, Englishman John Fryer, Bernier, and Manucci, who either possessed medical knowledge or posed as physicians, provided firsthand accounts of this practice.

Manucci describes how the physician’s head would be covered with a cloth by a eunuch, and he would be discreetly led to the patient’s room and back out again in the same manner. Remarkably, this encounter sometimes became a moment of dalliance, as Manucci recounts how the woman would grasp, kiss, and softly bite the physician’s hand as it reached through the curtain. In some instances, the woman would even press the physician’s hand against her breast, an occurrence Manucci pretended not to notice to avoid arousing suspicion from the matrons and eunuchs present. Another method of diagnosis, as mentioned by English traveller John Marshall, involved rubbing a handkerchief over the patient’s body and then placing it in a jar of water. The doctor would determine the cause of illness based on the smell and prescribe the appropriate medicine, all without seeing the patient’s face or feeling her pulse. Fryer, the East India Company’s official surgeon, had a rare opportunity to enter the harem and examine a sick woman. When a curtain accidentally fell, he saw a scene contrary to the stereotypical notion of debauchery. He witnessed the women engaged in ordinary household tasks, disappointing those who expected a sensationalized image of the harem.

The European travellers who journeyed to Mughal India held preconceived notions and biases regarding the Mughal Harem. They wove intricate stories and accounts, which must be regarded as imaginative narratives rather than reflective of actual reality. Some of these travellers, like Thomas Roe, propagated the belief that women such as Nur Jahan and her relatives held ultimate power, portraying Emperor Jahangir as a mere puppet. However, the Mughal women within the royal household possessed a multidimensional existence far beyond the stereotypes. They enjoyed respect, and leisure, and fulfilled various roles and responsibilities. Some wielded significant influence, issuing official orders and stamping documents with their own seals, demonstrating their authority under the Mughal state. European travellers, being outsiders and strangers to this world of women, relied on hearsay and bazaar gossip to construct their travel accounts, aiming to add spice and appeal to their narratives. Moreover, their Western-Christian background and traditions differed greatly from the Indian context, further limiting their understanding of the true significance of the Mughal Harem.

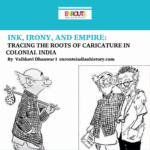

Jahangir with his ladies under a Canopy on a garden terrace, India, Mughal, circa 1620-40. Image Source : Sotheby’s

In conclusion, the travellers’ tales of the Mughal Harem must be approached with caution, acknowledging their reliance on gossip and their limited comprehension of the intricacies of this complex institution. By doing so, we can strive to unravel the true essence and significance of this fascinating aspect of Mughal India’s history.

References

- Book Beyond The Three Seas: Travellers Tale of Mughal India Edited by Michael H. Fisher

- Herath, T. (2016, January 10). Women and Orientalism: 19th-century Representations of the Harem by European female travelers and Ottoman women. Constellations, 7(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.29173/cons27054

- Lal, Ruby. “Historicizing the Harem: The Challenge of a Princess’s Memoir.” Feminist Studies, vol. 30, no. 3, 2004, pp. 590–616. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/20458986. Accessed 14 July 2023.

- The Mughal Harem By Kishori Saran Lal (z Lib.org) : Kishori Saran Lal . (n.d.). Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/the-mughal-harem-by-kishori-saran-lal-z-lib.org

- May 15, 2024

- 6 Min Read