What do Pahari frescos tell us about Punjabi Qissa and love stories?

- iamanoushkajain

- February 22, 2024

Love, the eternal force that propels our world, has woven its intricate threads across centuries. When love is fulfilled, it becomes a dream realized-a symphony of hearts. Yet, when love remains unfulfilled, it transforms into a poignant tragedy that resonates through time.

The Pahari Frescoes are the product of the art which developed in the Pahari or the hill regions of India. Some prominent centres where art flourished were Mandi, Kangra, Nurpur, Chamba, Basholi, Guler and Jammu. The impetus to the art in the hills was provided by Maharajah Ranjit Singh who defeated Sansar Chand of Kangra in 1808 and from there the artists who were working in the hills moved to his Lahore durbar as well. The maharaja was the founder of the ‘Sikh School of Art and these Pahari frescoes are a visual representation of the art which developed in the hills along with the durbar at Lahore and spread in the Punjab.

The artists sourced their six primary colours from natural sources; Red (was obtained from an indigenous clay called ‘Hurmachi’ and it was generally imported from the grofers who got them from the hills), Yellow (was derived from a yellow clay called Puri), Blue (was a mixture of ultramarine with process glue and lapis lazuli), Black (was derived from burnt coconut crust or the smoke from the earthen lamps) and White (burnt marble chips were drenched in water and these were then filtered to achieve a curd like substance, which was called Doga).

India, with its rich cultural and literary heritage, has been a fertile ground for exploring the myriad facets of love. From the divine romance of Radha and Krishna to the Qissa of Hir and Ranjha these stories depicting Indian Romance have inspired people through generations. The religious building of Pothimala, located in Guru Har Sahai; District Ferozepur; Punjab, stands a sanctuary adorned with Pahari frescoes. The Frescoes born from pigments ground in water, breathe life into the tales of love. Each fresco whispers of longing, sacrifice, and devotion. The real success of the murals and the Pahari frescoes was dependent on the handling of the mortar materials both before and after they were mixed. The layering of the ‘ground’ for the frescoes was done on wet plaster with pigments which were ground in water and it required a considerable skill to do so. The murals in the shrine fall in the category of Fresco since the paintings have been executed upon freshly laid wet lime plaster. Water is used as the vehicle for the dry-powder pigment to merge with the plaster, and with the setting of the plaster, the painting becomes an integral part of the wall.

This building of Pothimala was constructed in 1745 by Guru Jiwan Mal Sodhi, the seventh direct descendant of the celebrated fourth Sikh Guru, Guru Ram Das. The qissas find a visual depiction through the Pahari Frescoes. More than a hundred Pahari frescoes survive in the building today and they are a visual representation of tales which hold a cherished place in the literary tradition of the Punjab.

Dwelling into the realm of love, one treads the path of joyous unions between the lovers which in these frescoes are a visual representation of the God and the beloved as they are explored in Sufism. Sufism, in today’s context, is often described as a mystical tradition within Islam. However, its origins lie in the ancient designations of “fakirs” (meaning “poor men” in Arabic) and “dervishes” (referring to those who “stand by the door”). In Persian, the term becomes “Darvish”.

Among the qissas (narratives) that resonate, three stand out: Hir-Ranjha, Sohni-Mahiwal, and Sassi-Punnun. However, the qissas of Hir-Ranjha, and Sohni-Mahiwal are most popular. Frescoes of these two can be witnessed in the religious building of Pothimala. These artistic renderings are an integral part of our rich Indian folklore, capturing the essence of love, longing, and human emotions. The frescoes of both are discussed below:

Fresco of Hir and Ranjha

Composed in the fifteenth century by Warris Shah, this is the enchanting saga of Dhido Ranjha and Hir Sayal. Over time, numerous writers have woven their versions of this timeless Qissa (narrative). There are numerous versions of the Qissa which are available to the readers and many poets such as Bulleh Shah have written on them. His famous couplet “Ranjha Ranjha Krdi Ni Main Aape Ranjha Hui” is even today explored by the musicians.

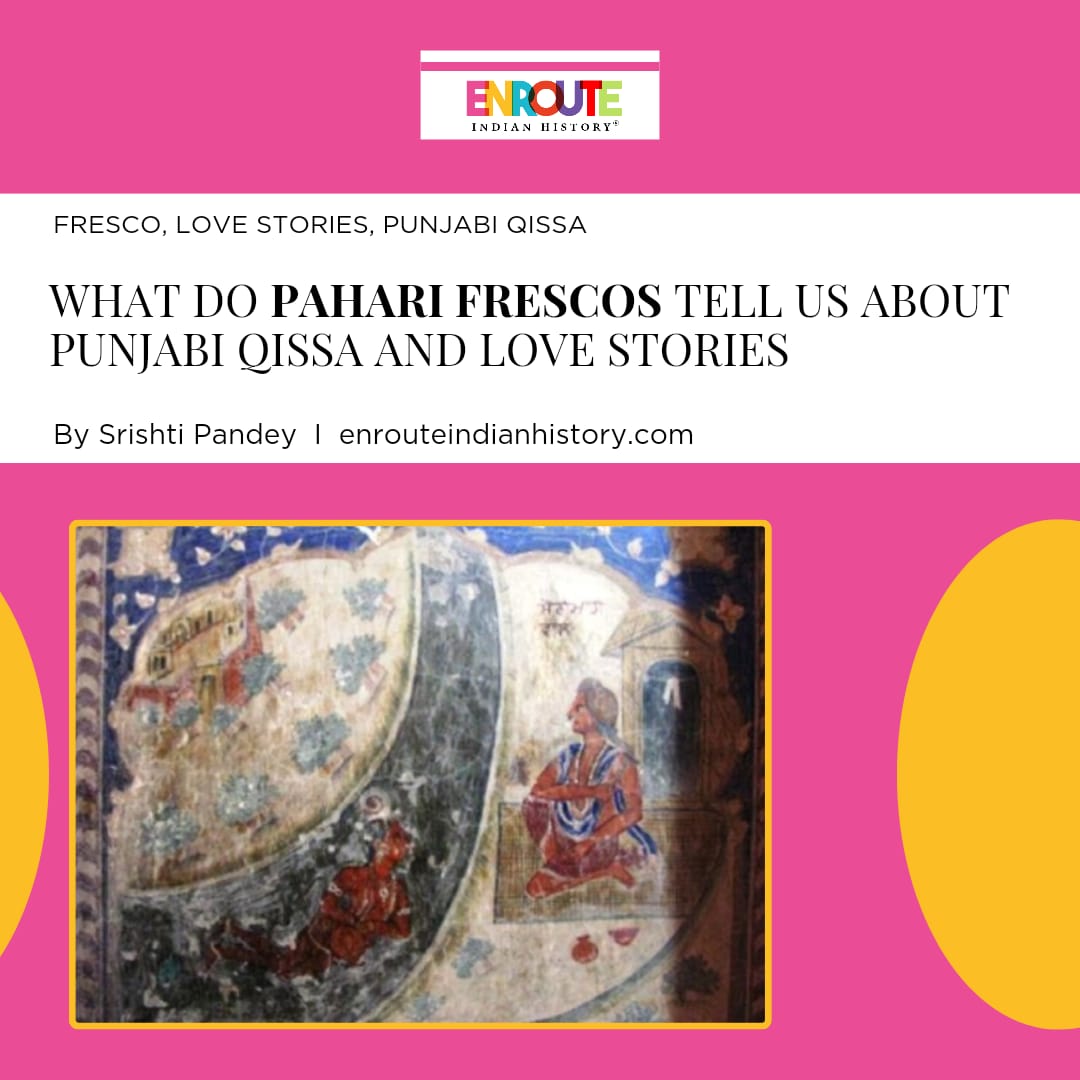

Fresco of Hir-Ranjha at Pothimala (Pandey; 2023)

This fresco here is a visual representation of the lovers at Pothimala. Hir is a representation of the devotee who is vying for a unification with her beloved Ranjha who is a representation of God.

The presence of a cow or sometimes a Buffalo is an indication towards the vocation of Ranjha as a cowherd and sometimes he is also shown holding a flute as well and that draws a strong association between him and the Hindu God Krishna. Cultural historian Denis Martinge, writes that the flute’s “music symbolises the pervading immanence of God”. In this fresco, his body is adorned with jewels. That is a departure from his description as poor a man.

The artists who painted these frescoes were from the Pahari region and in all probability the artist was aware of the story and Ranjha’s social status as the son of a wealthy zamindar. The artist has wonderfully blended the two aspects (the son of a zamindar and a cowherd) of his personality. His head gear resembles the traditional headgear or turban of Sikh men. The artist has evidently borrowed from the local cultures and customs of the village of Guru Harsahai. The depiction of the trees indicates their time together along the banks of the Chenab when he took the cows for grazing.

Hir’s face is distorted as the frescos have not been preserved too well. From what is left one can see her dressed in a ghagra-choli and some jewellery. She is shown to be holding the feet of an old man and this is a depiction of her requesting her uncle Keido to not reveal their alliance.

This fresco also operates on a multi-cultural level as well. The sufi allegory which comes out is equated to the bhakti devotion of Radha and Krishna. In this embodiment Lord Krishna is said to have inspired the persona of Ranjha and Radha of Hir. Radha and Hir pine for a unification with their beloved Krishna and Ranjha respectively and that also represents a human soul’s desire for unification with God or the divine. The flute playing is also common between the men in the two stories.

Hinduism scholar Glen Hayes writes, “In the loyalty of the cowherd girls, in particular Radha’s for Krishna, we have a representation of the human search for the sacred.” It is a lot like the Sufi search for the divine.

The fresco of this Indian Romance beautifully blends the two love stories. Most often this qissa is explored for the unhappy ending which is associated with it but in this fresco, one sees the divinity in their romance. Based in the realm of folklore this fresco depicts how a Pahari artist visualises the interplay between Hir-Ranjha and Radha-Krishna.

Fresco of Soni-Mahinwal

Fresco of Soni-Mahiwal at Pothimala (Pandey; 2023)

This is the story of Soni and Mahiwal. Like the story of Heer and Ranjha, this too developed around the banks of the river Chenab. This is the story of Soni (which means pretty in Punjabi) the daughter of a pot maker Tulla and Izzat Beig, a businessman from Uzbekistan. It explores how he spent his money to buy pottery which was made by Soni’s father and then how he was hired as the herder of buffaloes (when he exhausted all his money). This is how Izzat Beig came to be rechristened as Mahinwal.

Post her wedding she would meet Mahinwal for whom the earth under her feet was his dargah (this also indicates the devotional aspect of love in this Qissa representing Indian Romance) by staying afloat on the Chenab with the help of a pot. One fateful night her sister-in-law replaced her baked pot with an unbaked one and that pot while melting in the river caused Soni to drown.

In order to save her from the current of the river water, Mahinwal also jumped into the river but he was injured because he had carved a piece of his flesh to provide a meal for his Soni. The lovers could not tolerate the current and drowned in each other’s arms.

In this Soni is shown floating on the river with the help of a pot while Mahiwal sits waiting. He true to his description is a poor man and his hut is a visual proof of him being a man who cannot afford a high living. What is striking about this Pahari Fresco is that Soni is not clothed. Her body is adorned with jewelry and the lower part of her body is covered with a cloth. This visual depiction of Soni is very different from how she is portrayed in popular paintings and one has never really seen her in such a look. The river in the painting provides the geographical backdrop to the story/qissa.The Pahari Fresco however does not provide the viewer with any information on Mahiwal being a herder of water buffaloes as they have not been depicted in the painting. The viewer knows that the fresco is of Soni and Mahiwal as one can see a woman floating on the water with the help of an earthen pot.

These visual representations of Indian Folklore are also a celebration of the love which has inspired generations in the past and shall continue to do so in the future as well. Modern day artists have explored the love of Hir and Ranjha (Rahat Fateh Ali Khan and Aima Beg in ‘Heeray’ in the song which released in 2019 attempted at sharing the love of Hir and Ranjha with the youth of today) and Soni Mahinwal (Shipa Rao and Noorie have sung this in the form a song called ‘Paar Chanaa De’) in their renditions of the songs in Coke Studio and sufi poets have immortalized their love through their poems. These stories representing Indian Romance through Frescoes celebrate the Sufi belief that when a sufi saint dies he unites with his God. The ‘Urs’ at the sufi shrines have been celebrated with splendour and devotion. Even in the Punjab from where these qissas originate we have examples of the celebrations of the urs which take place at the shrines of Sakhi Sarvar, Baba Farid amongst others. The devotees celebrate the union of their saint with God and these qissas from the Indian Folklore celebrate the unification of Hir-Ranjha and Soni-Mahinwal.

References

- Carl Ernst, 2016, Sufism-An Introduction to The Mystical Tradition of Islam, Shambhala Boulder.

- Farina Mir, 2010, The Social Space of Language: Vernacular Culture in British Colonial Punjab, University of California Press.

- K.S. Kang, 1985, The Wall Paintings in Punjab and Haryana, Atma Ram and Sons.

- Srishti Pandey, 2023, “Intermingling of Religious Streams and Cultures in the Contemporary Society of Punjab in the Shared Space Explained Mainly Through Visual Flux”, Ph.D. thesis submitted to the Department of History & Culture, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi.