What Does a Season Look Like? Depictions of Raga Vasanta in Ragamala Art

- enrouteI

- March 20, 2024

What Does a Season Look Like?

Depictions of Raga Vasanta in Ragamala Art

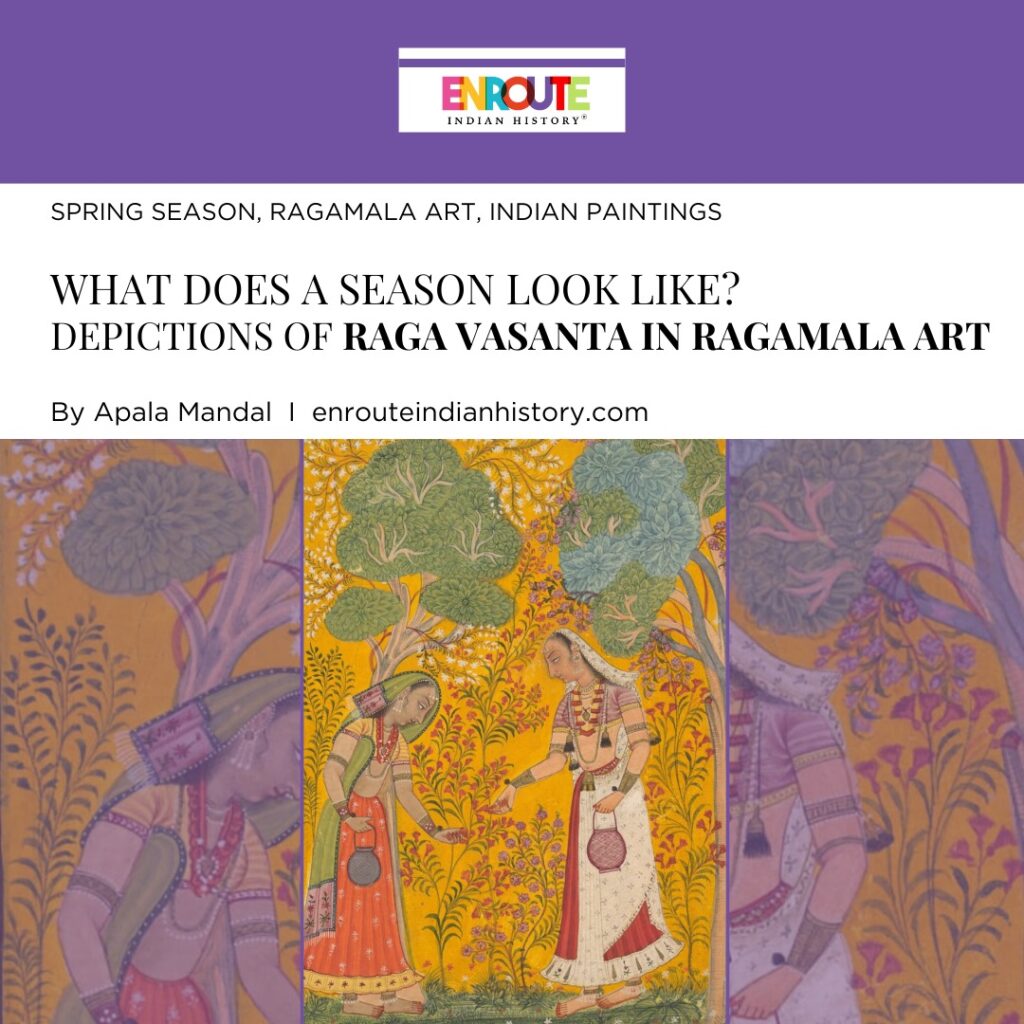

The spring season, with its vibrancy, energy and spirit of renewal, is a celebrated theme across art and music traditions around the world. One form of Indian painting illustrates this powerful link between art and music exceptionally well—the tradition of Ragamala art. Ragamala art bears a deep connection to Carnatic music and is inspired by the ragas or melodies that form the backbone of the Carnatic genre. Each raga can be drawn or depicted in Ragamala paintings, through the interplay of colours, characters, backdrops and borders. This article explores the history of Ragamala art, and specifically hones in on how artists through the ages have depicted Raga Vasanta, or Ragini Vasanta, the melody of the spring season.

Raga, the building block of Indian Classical Music:

Indian classical music can be divided into two broad schools or divisions: Hindustani classical music (more popular in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent) and Carnatic classical music (generally more popular in the southern part of the Indian subcontinent), and the two have more in common than in contrast (Sorrell and Narayan, 1980). The raga or the melody is the foundational unit for both schools, and alongside tala (beat or time markers), it offers a versatile toolkit for artistic experimentation.

According to Jameela Siddiqi, a cultural commentator for the BBC, a raga is more than just a collection of notes, a scale or a tune, and the English language lacks a true translation for the term (2020). Raga or raag comes from the Sanskrit word rang, which translates to “colour” in many Indian languages. Thus derived, a raga is an element of music that has the capacity to colour the mind a certain way. This capacity to invoke an emotional response is what makes ragas incredibly versatile and malleable. Even today, many songs in popular Indian cinema (in multiple languages) are based on ragas that have been sung for hundreds of years. Ragas are governed by strict rules of grammar and construction, are perfected through years of rigorous practice, and can be associated with certain times of the day or seasons of the year. In this manner, Raga Vasanta, the focal point of this article, is associated with the spring season and is lively, easy to recognise and full of hope and positivity.

(a)

(b)

Figure (a): Shyama Shastry, Shri Thyagaraja and Muttuswamy Dikshitar are known as the Three Jewels of Carnatic Music, or the Trinity of Carnatic Music, because of their unparalleled contribution to the genre. Source: India Today (2017)

Figure (b): A Tanjore-style Carnatic tambura, which is used as a drone to accompany a Carnatic performance, and establish harmony. Source: Wikimedia (2013)

The Ragamala Art Form:

Ragamala is a remarkable tradition of Indian painting that flourished across the subcontinent between the 16th and 19th centuries (Khetarpal 2019) and also enjoyed royal patronage. The term can be broken down into two parts—raga (melody) and mala (garland)—and the art form first finds mention in the 5th-century text, the Narada Shiksha, which explores the “relationship between sound and emotion” (Khetarpal 2019). In Ragamala art, each raga finds a shape, form and characteristics. In this manner, it becomes possible to paint music, and centuries of artists have used iconography, musical codes and poetry to indicate the time of day or season appropriate to the raga and its mood. The ragas were associated with divine power (Dulwich Picture Gallery) and bore strong links to certain times of the day or certain periods of the year. However, as the number of ragas increased, this tradition of Indian painting invented new ways to classify and connect the ragas. A popular way was to classify them into Raga families, with Ragas & their wives (Raginis), sons (Ragaputras) and Ragaputris (daughters) (Khetarpal 2019). Today, one of the most extensive digital collections of Ragamala art is maintained by the Cornell University Library. Using this and other sources, let us see how Raga Vasanta has been depicted and drawn.

Raga Vasanta in the Cornell Collection:

(c)

(d)

(e)

Figure (c): Raga Vasanta (n.d.), from Ragamala Collection 30 in the Cornell University Library.

Figure (d): Raga Vasanta (n.d), from Ragamala Collection 60 in the Cornell University Library.

Figure (e): Raga Vasanta (1650 CE), from Ragamala Collection 16 (Malwa) in the Cornell University Library.

These three depictions of Raga Vasanta have been chosen from over eighty such assemblages of Ragamala art collected by art photographer Klaus Ebeling between 1967 and 1972. They are now preserved by the Cornell University Library. Like nearly all Raga Vasanta paintings in Ragamala art, these examples showcase the festive, celebratory spirit of the spring season. In the first example, we see a dark-skinned Krishna, the principal deity associated with Raga Vasanta, dancing joyfully to the enchanting music played by the gopis (the milkmaids). One of these gopis plays a tambura while another holds a mridangam, another instrument commonly accompanying Carnatic music. There are fruit-laden trees in the background, monkeys and peacocks populate the forest, and the dark clouds at the top of the painting augur the onset of spring rain.

While gods are popular in early Ragamala art, the iconography and aesthetics in this genre of Indian paintings went through a shift in the mid-16th century. Inspired by the popular Bhakti movement, such paintings began depicting groups of people and exploring their relationship to architecture and landscape (Agarwal 2020). The second example from the Cornell collection is a great illustration of the same—a group of women play Holi, the iconic spring festival of colours, with a man. The women are depicted as happy, energetic, and joyful as they throw coloured water and powdered colour at each other. The man in the painting is seen embracing one of the women, pointing at another theme common to Raga Vasanta paintings: depictions of (especially young) love. Flowers bloom in the background to reflect this blossoming of emotions in the spring season.

As the format of miniature Ragamala art spread across the Indian subcontinent, different schools began interpreting and personalising it in their own ways. One manner of doing so was adapting the flora and fauna depicted in the background of these paintings. Thus, Raga Vasanta, as painted by the Bundi school, includes depictions of the mango blossoms that tend to emerge late in the spring. These are replaced by plum blossoms in the Kangra school Raga Vasanta paintings, in an effort to adapt the art style to the local character of the region. Another manner of marking stylistic differences was through each school’s techniques. Thus, the third example from the Cornell Collection stands in stark contrast with the first and second paintings’ art styles: the flat composition, blank backgrounds behind central characters, and bold hues (MAP Academy) help us easily associate the painting with the Malwa school of art.

Ragini Vasanti:

With its zigzagging flow from note to note, the Raga Vasanta is a melody imbued with energy, exuberance and hope. In some Ragamala art, the spring season is captured exclusively through the labour and leisure of women. Here are some examples of this variation, known as Ragini Vasanti:

(f)

(g)

(h)

Figure (f): Vasanti Ragini, a page from a Ragamala Art Series from Bilaspur (1710). Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Figure (g): Ragini Tori, a variation associated with Raga Vasanta (spring season), from a collection lithographed in 1887 by Sourindro Mohun Tagore and presented to Empress Victoria on the occasion of the fiftieth jubilee of her reign (Capwell 2002). Source: Sahapedia

Figure (h): A modern-day Indian painting of Ragini Vasanti by contemporary artist Kailash Raj, a descendant of a family of traditional Jaipur painters. Available for sale on Exotic India. Source: Exotic India

The time and location of the first example from the Metropolitan Museum of Art are easily identifiable, as the Bilaspur school of art was one of the first to make elongated, vertical Ragamala art in the early eighteenth century. In the painting, two women stand in a glorious springtime landscape, filling their baskets with flowers, which could be used for the purpose of decor, artwork or worship.

According to Agarwal (2020), the format of Ragamala art witnessed several changes between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries. Predominant among these was the emergence of depictions that showcased a central heroine in a state of longing and loss—a virahini or a woman separated from her soulmate. This change was again connected with the flourishing Bhakti movement and borrowed heavily from the allegory of “love in separation” and the painful alienation of the worshipper’s soul from the soul of god. The Ragini Tori from SM Tagore’s collection is a relatively late instance of Ragamala art, and, therefore, illustrates this thematic development. In this painting, the spring season is captured in the alluring musical performance of a sole heroine. She sits outdoors in the lush, green wilderness, and sings a song of separation so sorrowful that even the birds and beasts (depicted in this painting as wild deer) come to listen and commiserate.

Another change that took place during this period was the influence of European forms of art. As Agarwal (2020) explains, Ragamala art developed a distinct style in the court of Oudh under the patronage of Nawab Shuja’ ud-Daula and his son Asaf ud-Daula. These royals offered patronage to European artists such as Johan Zoffany and Tilly Kettle. They, in turn, incorporated Judeo-Christian imagery and devices into Ragamala art, such as angels above clouds, lightning and dramatic shadow play, and European-style halos. Eventually, however, the art form lost patronage and popularity.

Nonetheless, due to its diverse and rich history, contemporary artists who gravitate towards Ragamala art, like Kailash Raj, have many motifs, styles and traditions to choose from. In his Kangra-esque painting, Raj uses the yellow and white plum blossoms to ground his painting geographically. He is able to capture the rhythms and movements of spring in the posture of the woman plucking flowers and the drapes and folds of her clothing. The unique interplay of art, music and poetry in this style of Indian painting keeps fascination in the art form alive, and a perusal of Ragamala art gives us a valuable insight into how artists before us have experienced, imagined and captured the flourishing of the spring season and its power to renew life, love and spirits.

References:

Cornell University Library Digital Collections (n.d.). Ragamala Paintings. https://digital.library.cornell.edu/collections/ragamala.

Agarwal, S. (2020). Western India’s Ragamala Paintings Blend Music and Art into a Single Frame. Scroll.in. https://scroll.in/article/959474/western-indias-ragamala-paintings-blend-music-and-art-into-a-single-frame.

Capwell, C. (2002). A Ragamala for the Empress. Ethnomusicology, 46(2), p.197. https://doi.org/10.2307/852779.

Dulwich Picture Gallery (n.d.). Ragamala: An Introduction. Dulwich Picture Gallery. https://www.dulwichpicturegallery.org.uk/media/5775/dpg-raga-sbs-6.pdf.

Khetarpal, R. (2019). Ragmala Paintings: Visualizing Music & Mood. The Heritage Lab. https://www.theheritagelab.in/ragmala-paintings/.

MAP Academy (2022). Malwa School of Painting. MAP Academy. https://mapacademy.io/article/malwa-school-of-painting/

Siddiqi, J. (2020). What Is Raga? More than a tune, More than Melody. Darbar Arts Culture and Heritage Trust. https://www.darbar.org/article/what-is-raga-more-than-a-tune-more-than-melody.

Sorrell, N. and Narayan, R. (1980). Indian Music in Performance: a Practical Introduction. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- May 8, 2024

- 8 Min Read