What does Neolithic Pottery tell us about the diet of North-East India?

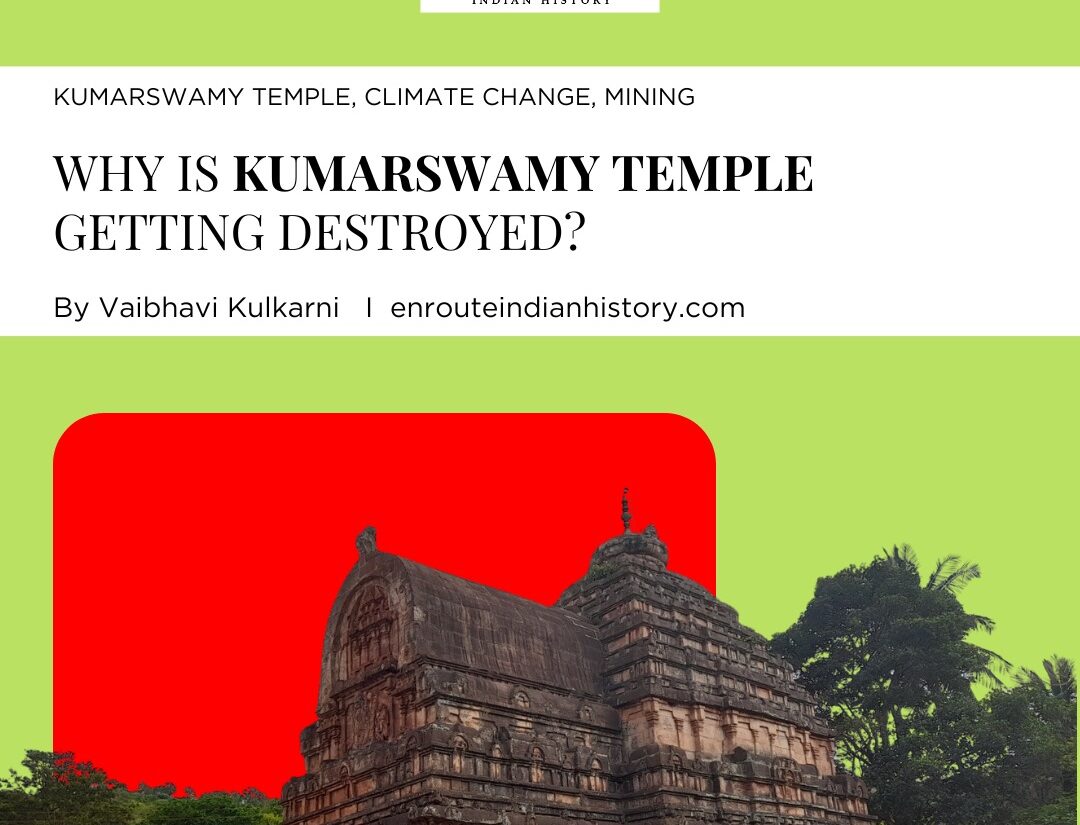

- EIH User

- January 23, 2024

Neolithic pottery can provide insightful information on a variety of facets of that era’s human existence. Pottery can reveal details about human migration and habitation patterns throughout archaeological sites. Archaeologists can determine trade networks and follow population movements by comparing and contrasting pottery types from different sites. Pottery’s patterns, motifs, and embellishments can provide details about a society’s aesthetic and symbolic elements. Specific types of pottery, including cooking pots or storage containers, can reveal information about the responsibilities that individuals performed in their communities. Disparities in the styles and methods of making pottery could also point to levels of economic specialisation. The kinds of clays used to make pottery and the accessibility of particular raw materials might reveal details about the environmental conditions in the area.

Different types of Red ware from the Ahar-Banas Complex, a Neolithic culture

Northeast India’s Neolithic ceramic culture is said to have been influenced by three major cultural centres of ancient Asian pottery making practices because of its advantageous geographic location at the intersection of Southeast, East, and South Asia. Following independence, a number of state archaeology departments in Northeast India as well as the universities in Guwahati, Dibrugarh, Shillong, and Manipur conducted excavations at a few sites. Parsi Parlo and Daporijo in Arunachal Pradesh; Daojali Hading, Sarutaru and Bambooti in Assam; Nongpok Keithelmanbi and Napachik in Manipur; Pynthorlangtein, Lawnongthroh, and Myrkhan in Meghalaya; and Chungliyimati, Purakha, Zolapkhan, and Photangkhun longkhap in Nagaland are the most significant excavated Neolithic sites in the area.

One could argue that the region’s Neolithic period is most notable for its cord-impressed or beater impressed pottery, tripod wares, some ill-fired and plain pottery, ground and polished tools, especially shouldered celts, and early rice-based farming. This is based on both surface and excavated material. According to Manjil Hazarika, these Neolithic cultural characteristics connect the area with their Southeast and East Asian equivalents in addition to the middle Ganga valley and Vindhyan region of India. He further elaborates that given that both the northern Southeast Asian Neolithic and the Northeast Indian Neolithic were descended from the Yangtze Valley Neolithic, there is little doubt that the two cultures shared close ties.

Close-up shot of corded ware pottery, from Daojali Hading

As the name implies, ceramics with cord impressions bear cord-impressions, either entirely or partially, primarily on the exterior. A cord-wrapped paddle is used to create impressions as a decorative pattern, or the impressions stay on the surface as a byproduct of pounding and shaping the pot until it is leather-hard. These impressions can be viewed as decorative ornamentation or as merely a technological potting procedure or both, in addition to any functional component that may exist. The paddle is wrapped in cords to make it easier for beating the sticky clay because they keep the paddle from sticking to the clay.

A significant characteristic of the Neolithic pottery found in the area is the presence of tripod wares, commonly known as tripod legged ware. This distinctive type of pottery is a defining feature of the ceramic industry at the Napachik and Laimenai sites in Manipur. The tripod legs, primarily reddish brown in hue but with some variations in grey and dark grey, are crafted as solid entities and manufactured separately. Additionally, these tripod legs exhibit variations in length, with some being long and others short.

Excavation in Daojali Hading, 1961-63

In addition to the cord-impressed and tripod wares discovered in Neolithic contexts, straightforward plain handmade pottery has been documented in numerous sites.

The appearance of Corded Ware pottery in different regions, including parts of Europe, Central Asia, and Northeast India, has led to discussions about cultural diffusion and connections between distant populations during the Neolithic period.

With regards to diet, remaining organic remains on pottery shards can be identified and examined by archaeologists using residue analysis. Traces of food and drink that were previously cooked or stored in the pottery may be present in these remnants. Through the identification of particular substances, such proteins, carbohydrates, or lipids, scientists can learn more about the kinds of plants and animals that are consumed. Through residue analysis of ceramics, researchers can determine the primary foods of a given population. Pottery surfaces can bear the imprints of various cooking methods. Evolving pottery assemblages across time can provide insight on dietary fluctuations by season. For instance, certain seasons may have seen a greater availability of a particular species of plant or animal.

Northeast India is a sub-tropical region with a diverse range of plants that is situated in the transitional zone between the Indian, Indo-Burman-Malaysian, and Indo-Chinese regions. The availability of perennial water, uplands for growing tubers, roots and lowlands for cereal crops, such as rice, seasonality of rainfall and climate, and fertile lands are essential requirements for early agriculture. These factors point to the region’s pivotal role in the early domestication of plants.

Indian Jaintia tribalwomen work in a terrace field near Jowai town, in the Jaintia Hills District, about 44 kms from Shillong, the capital of Meghalaya state | Biju Boro/AFP

But sadly, in contrast to the extensive history of the Neolithic period for the rest of the subcontinent, our understanding of the initial stages of farming and animal domestication in Northeast India is quite limited. In rare places like Chungliyimati archaeo-botanical remains include Oryza nivara, Oryza rufipogon, Oryza sativa, Siteria sp., Triticum aestivum, and Hordeum vulgare. Investigations of other Naga ancestral sites have reported remains of cultivated rice and millet, Bos indicus, Bos frontalis, Bubalus bubalis, Sus scrofa, cervus, jungle fowl, barking deer and wild boar.

But many scholars believe that Northeast India played a crucial role in the domestication of several vital food plants for humanity, notably rice. Ian. C. Glover in fact wrote in 1985 that with over 20,000 (over 50,000) known species, India is the core of the largest diversity of domesticated rice, and Northeast India is the most advantageous region for the origin of domesticated rice.

In a paper on the Neolithic cultures of Northeast India and adjoining regions, K.N. Dikshit and M. Hazarika write about the geographical position referred to as “Monsoon Asia”, comprising India, southern foot of the Himalaya, Southeast Asia, south China east of Sichuan and Yunnan provinces and more. Here, evidence of prehistoric societies that practised rice farming, hunting, and fishing has been found in the regions of the Yangtze, Mekong, and Ganges that flow across Monsoon Asia and around 5000 BCE, rice-growing settled agricultural societies gradually expanded throughout Southeast Asia, encompassing northeastern India, via the Yangtze River system.

But conversely, Fuller et al.’s recent work (2008, 2017) has raised doubts about the dating of early rice-producing communities in central China. They propose that many findings initially thought to be evidence of domesticated rice are, in fact, wild rice, and that the actual process of domestication began around 6500 BP. In a more recent paper by R.M. Blench , a similar perspective is presented, asserting that reconstructing agricultural terms in Proto-Sino-Tibetan is challenging due to the absence of definitive attestations in numerous subgroups, particularly in the Himalayan and Northeast Indian branches. According to Blench, agriculture likely developed significantly later after the initial dispersal of Sino-Tibetan people. This viewpoint aligns with the observation of the absence of conventional grain-based agriculture, as implied in much of the Sino-Tibetan literature.

The ample availability of wild varieties of edible plants however likely played a crucial role in supporting the adaptive strategies of early humans, serving as a valuable food resource. In an ethnographic context, various tribal groups in Northeast India are observed gathering and hunting a diverse range of wild plants and animal food resources, possessing both nutritional and medicinal value, across different landscapes. Forests and jungles in the region offer a wealth of edible shoots, roots, tubers, leaves, flowers, fruits, and seeds, which are consumed either in their raw state or after being cooked.

Archaeological evidence does not strongly support the hypothesis of bamboo’s utilisation as a raw material in various activities during the prehistoric period. The perishable nature of bamboo makes it challenging to recover or document bamboo artefacts in archaeological contexts. Some research has explored the potential use of bamboo based on experimental microscopic studies examining cut-marks made by bamboo knives. These kinds of experiments show that the distinctive characteristics of the cut marks generated by stone and bamboo blades differ morphologically. The continuing multifaceted use of bamboo in the region, serving as a tool in activities such as hunting, fishing, and cutting, may indicate a broader significance of bamboo tools in prehistoric times.

According to T.C. Sharma (1990), there was a popular agricultural system in Northeast India during the Neolithic era that was akin to shifting agriculture. The majority of tribal members believe that this agriculture has been popular for generations and is still a common way to use land, serving as the foundation for maintenance and subsistence cultivation providing social stability and cultural values for those residing in sparsely populated areas.

Fuller argues that gaining insight into pre-sedentary cultivation necessitates examining evidence from locations where individuals were still nomadic but in the early phases of cultivation. The inception of cultivation and domestication probably occurred within more mobile communities, although providing archaeological documentation is extremely challenging and this precisely is the case with Northeast India. But regardless, in the contemporary context, this area displays signs of rotating cultivation, the farming of yams and taro, the construction of stone and wooden memorials for the deceased, and the use of Austro-Asiatic languages.

Slash-and-burn cultivation during Neolithic Age.

But overall if we look at the rest of the subcontinent, pottery does provide us some important details on the kind of lives led by the people during the Neolithic period. A page for the National Museum of Denmark website reads as follows – “It is no coincidence that the use of pottery began in earnest at the same time as agriculture appeared. Arable farming and cattle-breeding meant that people needed pots for storing cereals and dairy products. Pottery vessels were also used at the end of the Mesolithic period, but they were a little cruder and less varied. In the Neolithic period several types of vessel were made. The shapes and decorations must have had both a symbolic and a practical significance. Some pottery vessels are not decorated at all and were probably everyday pots used in the household. Other vessels are richly decorated; many were placed outside the Neolithic barrows – probably as sacrificial vessels.”

Reference

- Dikshit, K. N., & Hazarika, M. (2012). The Neolithic cultures of Northeast India and adjoining regions: A comparative study. Journal of Indian Ocean Archaeology, 7(8), 98-148.

- Rao, S. N. (1977). Continuity and survival of Neolithic traditions in Northeastern India. Asian Perspectives, 20(2), 191-205.

- Hazarika, M., & Bae, K. (2019). Neolithic Pottery of Eastern Himalaya and Northeast India. Development of Neolithic Cultures and Diversity of Pottery, Amsadong Site Research Series, 3, 79-108.

- Hazarika, M. (2013, September). Prehistoric Cultural Affinities Between Southeast Asia, East Asia and Northeast India: An Exploration. In Unearthing Southeast Asia’s Past, Selected Papers from the 12th International Conference of the European Association of South East Asian Archaeologists (Vol. 1, pp. 16-25).

- Jamir, T. (2012). Piecing together from fragments: Re-evaluating the ‘neolithic situation’ in Northeast India. Neolithic-Chalcolithic Cultures of Eastern India, 45-68.

- Hazarika, M. (2012). Cord-impressed Pottery in Neolithic-Chalcolithic Context of Eastern India. Neolithic-Chalcolithic Cultures of Eastern India, 78-110.

- https://en.natmus.dk/historical-knowledge/denmark/prehistoric-period-until-1050-ad/the-neolithic-period/the-skarpsalling-pot/what-was-the-pottery-used-for/

Image credit

- Research Gate

- Research Gate

- Research Gate

- Scroll

- Science china press

- May 15, 2024

- 6 Min Read